Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute.

For estate jewelers and jewelry historians, hallmarks provide an extra source of information to accurately date a jewelry object and determine by whom it was made. The most encountered hallmark on jewelry is undoubtedly the “purity” mark which indicates the total amount of gold or silver used to manufacture a coveted jewel. Although the study of hallmarks serves as a wonderful research avocation to many involved in the antique trade, a trained professional can, and should, put such a desired object in the proper time frame without the presence of such marks. Contemporary jewelry historians use hallmarks for research purposes but these hallmarks were never intended to make the life of appraisers easier. Rather, they were an early type of consumer protection.

In the first century BC, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio described Archimedes’ discovery of hydrostatic weighing. King Hiero II of Syracuse gave Archimedes the assignment to investigate the purity of a newly commissioned golden wreath, believing silver was added to the gold content. The famous story ends with Archimedes running through the streets shouting “eureka, eureka” after he found a means to expose the deceit while he sat in a bathtub. Although the technicalities in this legendary story are most likely based on myth, it does give an early account of fraud with precious metals.

Since pre-Roman times gold and silver have been used as currency or as the counter deposit for money and one can imagine that a not-so-scrupulous person, with little fear of severe punishments, would find a means to tamper with the precious metal. Scraping a small portion of a gold coin, or diluting a golden ornament with non-precious metals while selling it as pure gold, could in time build a small fortune and that type of counterfeiting was not uncommon in days gone by. At the present time, labour costs exceed the profits to do so. It was for this reason that in the late middle ages, several European sovereigns issued regulations requiring that all gold and silver artifacts be marked with a unique stamp to identify the maker of the object; a responsibility mark to protect consumers.

From medieval times to the mid-19th century, hallmarks were used only as a means of consumer protection. This changed around 1840 when falsified hallmarks, named “pseudo marks” appeared on the market to dodge taxes. In those days the English government raised taxes on imported gold and silver work, with the exemption of antique items. Paying taxes has never been on the priority list of entrepreneurs and some gold and silversmiths in Germany and the Netherlands started stamping marks on their jewelry and silver work that mimicked antique hallmarks. A second factor was the renewed interest in antique artifacts of the applied arts that was kindled by the first World Exhibition in London (1851). The smiths of the day, mostly trained in the old tradition, were more than happy to provide the market with freshly crafted “antiques” and the mimicked hallmarks added to the authenticity of those desired objects.

As there had never been a real prior interest in hallmarks, other than identifying the people responsible for the quality of the precious metal, these marks were interpreted as genuine foreign antique marks by the customs officers and collectors. This deceit lasted until around the turn of the 20th century.

Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute.

Many collectors and civil servants responsible for tax collection, had no understanding of foreign antique marks. Their job was made even more difficult due to the fact that many objects were made in the neo-styles, such as neo-gothic, neo-renaissance and neo-baroque. These neo-style items looked very much like the artifacts made in their respective era. From around 1865 people started noticing repetitive patterns and the study of hallmarks began, exposing many frauds in decades to follow. By 1900 a good hallmark inventory was at hand and the risks of an item being destroyed, due to falsified hallmarks, soon outweighed the profits of tax evasion. By that time the general taste had changed from eclecticism to Art Nouveau and Edwardian.

Thanks to the hallmark research that began in the late 1800s, a good picture of hallmarking practices throughout the ages is now readily available. The interpretation of these hallmarks, however, requires specific training and a keen eye. Especially in countries with no governmental assay offices, like the USA, the need for in-shop trained professionals in this field is required to interpret these stamps correctly. On a large percentage of antique jewelry, these hallmarks are, due to various reasons, absent and estimations on the origin can only be done through careful observation and, if present, the correct interpretation of accompanying documentation. When hallmarks are present, they can add greatly to the value of the coveted object and that is especially true when the stamp is rare or that of an important maker.

While in the United Kingdom smiths incorporated the hallmarks in the design, the sentiment amongst most precious metalsmiths is that they do not want someone to punch stamps on objects they created with great care and hard labour. When it could be avoided, for instance when it was not mandatory, the smiths would choose not to have their items marked. Other reasons hallmarks are not found on jewelry include repairs done in the course of the life of the item or that the article was exempt from hallmarking. This exemption was for items that were under a certain weight or were too delicate to be marked without damage.

For the neophyte, many marks may seem contradictory as they do not fulfill the ideal image as seen in reference books. It is, for instance, entirely possible for 18th-century jewelry to carry both 18th-century French as well as 19th-century English marks. To the initiated, this only adds to the allure of the precious objects.

The tradition of jewelry manufacturing in the USA started only around 1840 and one can find many pre-20th century pieces in the USA stamped with European marks. This was for the sole reason that many settlers had strong ties to – and traded with – the “old countries”. It was not until 1906 that regulations concerning “hallmarking” were issued in the USA. As there is no supervised system of hallmarking in the USA (nor in many other countries), one cannot technically refer to it as “hallmarking” in the strict sense, rather they should be referred to as “manufacturers’ marks”.

On, relatively, large objects such as silverware (like candlesticks and flatware) full sets of hallmarks were stamped. On smaller items such as jewelry, this was often not possible without damaging the item. Therefore smaller copies of the stamps were used on those items and usually fewer of them (not a full set). A full set is, in general, made up of a purity mark, a maker’s mark, a date letter and a town mark. Some of these marks are combined in certain countries.

While searching for hallmarks on jewelry, one needs a good jeweler’s loupe that magnifies at least ten times and of course, one needs to exert a lot of patience. When a legible mark is found and the mark is not recognized, one needs to look at it from different directions as chances are that one looks at it upside-down. Usually, when jewelry is marked in a country with a mandatory hallmarking system, it contains a purity mark, as well as a maker’s mark.

Those that enjoy the study of hallmarking can get very excited when a rare or important stamp is encountered.

Overview of Different Stamps

The interpretation of hallmarks and stamps is dependent on the knowledge of the one who judges them and mistakes can be easily made by the neophyte. At all times the marks that are found need to be in agreement with other indicators, such as style and manufacturing technique.

There are four main types of hallmarks that can give vital information on the origins of jewelry items.

- Purity marks

- Maker’s Marks

- Date Letters

- Town Marks

Some of these marks can be bundled in one mark depending on origin, or they can be absent due to various reasons. When a mark is found that carries a crown, it usually indicates that it was marked in a country that has or had a monarch as the head of state.

Purity Marks

Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute

The purity mark is one of the first stamps to look for when inspecting jewelry. When such a mark is found, it reveals the percentage of precious metal is used to create the item.

Gold in its purest form is very soft and is not very suitable to create jewelry from. In days gone by the people who could afford golden body ornaments were not concerned with household chores, that privilege was given to domestic servants. Consequently, their jewelry was not very susceptible to wear and tear. Later, there came a need to give extra strength to the precious metal and other metals were added to make the jewels more durable, these diluted metals are referred to as “alloys”. Alloys are a mixture of different metals and the amount of precious metal used to create such an alloy is named the “purity” of the alloy. Up until the mid-20th century, this purity was primarily expressed in karats (or carats in the English Commonwealth). In the USA the karat weight is abbreviated as “k”, while in Great Britain it is abbreviated as “ct”, which provides a good clue to the possible origin.

Karat weight is expressed in divisions of 24, with 24 being the purest gold. When one finds a purity mark of 18k, it indicates that the alloy to create the jewelry is made out of 18 parts of gold and 6 parts of other metal. To translate that to percentages we divide 18 by 24 and multiply it by 100. In the case of 18 karat gold, the simple equation will be (18/24) x 100 = 75%.

As more and more countries are transferring to the metric system, you will find the purity being expressed as parts of thousands. 1000/1000 is pure gold in the metric system and an 18 karat gold item will therefore be stamped as 750 (leaving out the trailing “/1000”).

While in the USA, and some other countries, the purity is clearly indicated by stamps such as 14k and 18k, there are many other countries that indicate precious metal purity marks with pictorial marks and one needs a good library to discriminate the many stamps that were (and are) used worldwide.

Silver and platinum purity stamps are much like those for gold but the pictorials c.q. numericals are different. The phrase “sterling” is stamped on many post-1870 USA pieces. One will not find that mark on, for instance, English pieces, unless they were fabricated for export. Prior to 1870, the silver standard in the USA was “coin silver” (900/1000) which is slightly lower than sterling (925/1000) silver.

Maker’s Marks

Traditionally the maker’s mark is the main responsibility mark for the gold (or platinum/silver) content of an artifact. When problems arise, the maker (or company) can be identified and held responsible. The maker’s mark does not necessarily mean that the item was made by the one whose mark is struck, it merely indicates the person who was responsible for the purity. In modern times it also serves as a trademark, much like why Coca-Cola labels its bottles. Important names commission an added value.

In many countries with a long-standing tradition of mandatory hallmarking, these maker’s marks had to be unique and copies of these marks were well-kept in the archives of the guilds. Usually, these stamps carried the initials of the maker accompanied by a pictorial mark in a specific contour. Sometimes regulations required the contour to be a specific shape, like the lozenge shape that is mandatory for French maker’s marks from 1797 onward. In the USA these marks were made mandatory only in 1961 and they can be in the form of a registered trademark, or the name of the maker/firm in full. On English, and later on USA, pieces one will find a lot of maker’s marks containing an ampersand as in the mark “J & S”, which could indicate the (fictional) firm “Johnson and Stewart”. The use of an ampersand is typical for British (and their former colonies) maker’s marks.

In most cases, this stamp is struck by the manufacturer and is therefore not a hallmark in the strictest sense, although the mark needs to be registered at the assay office.

Date Letters

Date letters were first introduced in 1478 in London. New English regulations at the time required all gold and silver artifacts to be assayed by a governmentally controlled body, at Goldsmith’s Hall in London. Here lies the origin of the word “hallmark“; it had to be marked at the “Hall”. The head assayer was usually chosen from one of the most prominent guild members and the position changed hands every year. To prevent fraud by the assayer a new assay responsibility mark was introduced and this took the form of a letter from the alphabet. In practice that meant that every 25 years (some letters were skipped) the same letter should be used. To prevent confusion a different letter font and/or contour around the letters was used every cycle.

While the original purpose of the letters was to indicate the responsible assay master, today it serves as a “date letter” to indicate when the item was assayed. In daily practice, jewelry historians are hardly ever interested in the name of the assay officer behind that responsibility letter. The date letter indicates the year the object was offered for hallmarking, not the time of fabrication as is popularly believed. In recent years the use of a date letter has been made voluntary in the UK. One will hardly ever find a date letter on delicate jewelry pieces because there was often no room for a full set of marks on such items.

Town Marks

Due to the expansion of financial prosperity in the late middle ages and the Renaissance hitherto, many nations with a mandatory hallmarking system opened new assay offices dispersed across the country in order to accommodate local precious metalsmiths. To discern between the marks used in those towns a new mark was introduced, the town mark. This mark usually took the form of the city’s heraldic shield or another distinguishable pictorial mark. The assay mark of Birmingham, England is an anchor which is not very logical as Birmingham does not have a port, nor is it located near a sea or other open water. The anchor refers to the Crown & Anchor Tavern where the decision on the mark was made. Today the Birmingham assay office is the largest assay office in the world and one can find many items that have been struck with this town mark.

In some systems, such as the Dutch hallmarking system, the combination of the town mark with another mark indicated the purity of the precious metal from which a jewel or larger item was made.

In France, it was customary to have a purity mark for Paris and another one for items made in the provinces (departments), the latter were sometimes individually distinguished by a numerical.

Other Marks

Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute.

There are many other stamps that one can find on jewelry items that are not hallmarks but are important to properly judge jewelry. Some of them are outlined here.

- Designer Marks are marks that are stamped on jewelry to indicate the designer. A lot of items made under the responsibility of the famous Russian manufacturer Fabergé carry a designer mark. In addition, some pieces that were made in the Art Nouveau period carry designer stamps.

- Tally Marks are sometimes found on USA and British items to indicate the journeyman who actually created the piece.

- Retailer Marks indicate that a piece was sold through a specific outlet, mostly through large firms like Tiffany & Co. and other large branded stores.

- Duty Marks may be struck on items to indicate that taxes have been paid on domestic jewels.

- Import and Export Marks may be struck on items to indicate that taxes have been paid or that items were exempt from taxes.

- Patent and Inventory Numbers usually take the form of long numbers and in conjunction with other marks or stylistics, they can aid in the dating of jewelry. A firm that almost always stamps an inventory mark is the famous French jeweler Cartier. Boucher, a USA firm, patented many jewelry designs from the 1930s through the 1960s and their patent stamps are usually depicted as a sequence of numbers.

Overview of Hallmarking on Jewelry in the USA, Great Britain, France & Germany

USA

The stamping of jewelry made from precious metals is regulated in the USA by the National Gold and Silver Stamping Act of 1906 (also known as the Jewelers’ Liability Act). When a maker chooses to mark such an item with a purity mark (either in pictorial or numerical form), the maker is responsible for the accuracy of the alloy (with some tolerance). The 1906 act did however not require the maker to put a responsibility mark, or maker’s mark, on the jewel. It was not until 1961 that a responsibility mark became mandatory on jewelry with purity marks. This mark can be in the form of a trademark or the family name of the maker in full. A maker is not required to stamp a purity mark on the articles, but when he or she does the act provides for the legislation.

As the act does not mention any lower values of purity, one can find marks of any fineness on jewelry, although 10k and 14k are the most common. For items made from silver, the sterling alloy is the most ordinary. On 19th-century jewelry, one can occasionally find a “coin silver” mark, this indicates a purity of 900/1000.

One can usually easily distinguish gold marks used in the USA from those in Great Britain by the abbreviation. The UK spelling is “carat” which is shortened as “ct”, while in the USA the abbreviation is “k” for “karat”.

On jewelry objects made in the USA before circa 1900, it is not common to find any marks.

Great Britain

Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute.

When Great Britain is discussed in relation to hallmarking, it usually also includes Ireland as it was part of Great Britain until 1921. Hallmarking in Great Britain started as early as 1300 and is now regulated through the Hallmarking Act of 1973. Although there were many changes in the way items needed to be hallmarked during the last 700 years, it, in general, remained the same until 1999. Silver items were stamped with either a lion or the Britannia mark indicating 925/1000 and 958/1000 resp., while gold of 18ct and 22ct was stamped with a crown and a numerical (18 or 22). Alloys of lower fineness were stamped with a mark that indicated both the carat weight, as well as the fineness in thousands, like 9 and 375.

Up to 1854, the legal standards for gold were 18ct and 22ct. In 1854 these standards were broadened with 15ct, 12ct, and 9ct. In 1932 the 12ct and 15ct standards for gold were abolished in favor of the 14ct mark. For Scotland and Ireland, the marks and standards are marginally different.

Although all jewelry (with some exemptions) is thought to require a full array of stamps, jewelry was usually – prior to 1973 – exempt from hallmarking with the exception of wedding and mourning rings.12 One will therefore find many items of British origin that bear only a maker’s mark and a purity mark. The full array should also include a date letter and an assay office mark and these were struck at the request of the purchaser. The date letter is made non-compulsory as of 1999. In 1974 a pictorial mark in the form of an orb was introduced as a purity mark for platinum.

Many makers in the USA use pictorial trademarks that resemble English hallmarks and care must be taken not to confuse the two. These American marks are not considered pseudo marks.

France

The French hallmarking system dates back to the 13th century and is regarded as the most complex due to the many marks one can encounter. This is especially true for large silverware. For smaller items, such as jewelry, the system is much more simplified and comprises a mark indicating the precious metal and a maker’s mark. Since 1838 an eagle’s head indicates a gold purity of at least 18 karat and the boar’s head or crab mark is stamped on articles with a minimum fineness of 800/1000 silver. These three marks are the most prolific on French jewelry. The crab was used for articles made in the departments while the boar’s head was the mark of the Paris assay office. Since 1912 a dog’s head is used as the mark for platinum.

Although French law requires all gold jewelry to have a minimum purity of 18 karat, items that are intended for export may be marked with the pictorial marks for 9k and 14k.

As of 1797, the maker’s mark needs to be in a lozenge shield with the initials of the maker incorporated in it. Although makers from other countries used lozenge-shaped responsibility marks, these are usually good indicators that the item is of French origin. Before 1797 these maker’s marks consisted of initials in a crowned shield.

One can find the purity marks on any, seemingly random, place on a jewelry item but there are strict regulations on the positioning of these marks. Usually, we are not concerned with the strict order of placement as the regulations for this take up a multitude of pages. One can also find combinations of the purity marks when the jewelry is made from different precious metals.

Germany

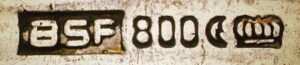

Image Courtesy of the Hallmark Research Institute.

Like the USA, Germany does not have a hallmarking system that is overseen by an independent body. Instead, manufacturers stamp the marks on the objects themselves.

From 1884 to the present, golden jewelry objects can be of any alloy and usually carry only the maker’s mark and a purity mark. The purity mark can be a numerical in thousands as 585 for 14 karat gold or indicated in karats, like 18k or both combined into one mark. For silver jewelry, there are two standards, 800/1000 and 925/000. When the silver content is at least 800/1000 silver, a German mark in the form of a crown with a half moon is struck on the jewelry next to an indication of the fineness in thousands (800 or 925) and a maker’s mark. Large golden objects and watch cases need to have a purity of at least 14 karat and may be marked with the crown in a sun.

Prior to 1884, each city had its own town mark and the guilds regulated the system. The purity was indicated in “Löthig” with 16 löthig being pure silver or gold. A very common mark on these items is “13” indicating a fineness of 13 löthig or 812.5/1000.

The town Hanau is of special interest as many pseudo marks are struck on objects made there in the 19th century. Contrary to most other cities, the trade in Hanau was not strictly regulated and every gold or silversmith could provide a finished item with the marks he or she chose. In the era where neo-styles were the fashion, many objects were struck with fantasy marks that mimicked antique hallmarks from other countries. As this was a legal practice in Hanau, there is some uncertainty as to whether this was done to commit fraud or to give a finishing touch to the article.