…There were couches of gold and silver on a mosaic pavement of porphyry, marble, mother-of-pearl and other costly stones.1

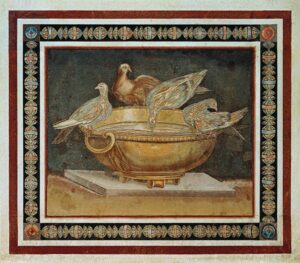

Photo Courtesy of The Capitoline Museum.

The first use of decorating surfaces, especially walls and pavements, with mosaics is attributed to the ancient Greek2 and3 from there spread over the Persian and Roman territories in Biblical times. Although relatively small objects with mosaic surfaces are known, mosaic jewelry usually dates from about 1810 – hitherto, with several attention peaks in the 19th century. This type of jewelry mainly comes from Italy – most prominently from Rome and Florence, but also from Naples and Switzerland – and became popular first as souvenir jewelry and later by the innovative use of this decoration technique by Castellani which caught the attention of the beau monde.

Early records as the Bible (Esther 1) date this art back to at least the 5th century BC4 and Pliny gave testimony of it in the 1st century AD. In his The Natural History, Pliny describes two-floor mosaics from which copies still exist; the “unswept room” and the “doves of Pliny” both attributed to Sosos of Perguma (present-day Turkey). Especially the latter theme has been copied many times and one can find it in jewelry mosaics or cameos from the 19th century onwards. The earliest Roman copy, discovered in 1737 at Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli, is now in the collection of the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

Much like in paintings, mosaics underwent an evolution and were created in different styles which are not easily differentiated by the uninitiated as the style differences can be very subtle. In general, we can divide mosaics into 4 groups,5 although there are more.

- Opus Tesselatum

This is probably the oldest of all mosaic styles and consists of marble, and other hardstone, cubes that are laid out on floors in – two-toned – geometric designs. These square tiles are named tesserae.

- Opus Sectile

In this style, the hard stones are shaped and the forms fitted together as a jigsaw puzzle. It was mainly used for pavements, but also for ceilings and murals. The pietra dura technique is a descendant of this technique, with the main difference that opus sectile relates to geometric designs while pietra dura is more figurative. This ancient style was revived in the 16th century under the rule of the Medici (Grand Duke Ferdinando I) who founded a school devoted to this style. The floor of the St. Peter Basilica in the Vatican and the Taj Mahal in India are examples of the opus sectile c.q. pietra dura style.

- Opus Figlinum

In this mosaic style, glass tesserae are used to form abstract figurative designs, mainly for murals.

- Opus Vermiculatum

This is the most elaborate style of tesserae mosaics and is very figurative. The tesserae can be of glass and/or hard stone to depict images in a true way. We can divide this style further into 3 categories by size and attention to detail, with the minor having the most detail c.q. finer tesserae. Some mosaics have so much detail that they resemble oil paintings when viewed from just a few passes away.- major – for pavements and ceilings

- medium – for murals

- minor – for portable items

Other notable styles include:

- Opus Asaroton

An Opus Vermiculatum with pieces fallen from the table as in Sosos’s “swept floor” which gives a trompe l’oeil effect. - Opus Incertum

These look like “terrazzo” mosaics made from irregular, but not calibrated marble slabs.

In jewelry, we can divide mosaics into two categories.

- Micromosaics

This is a derivation of Opus Vermiculatum and is made from, usually, glass bricks or cubes named smalti. Most jewelry of this kind comes from Rome, Italy. - Pietra dura

This style is descendent from the Opus Sectile technique and is associated with the city of Florence, Italy.

Although mosaics have always been made, there are some peaks when they are more often created. For jewelry, decorated with this technique, we can narrow that period down to the late 18th and the whole of the 19th century, although they are still being produced. As popularity grew, mainly through tourism, more workshops started specializing in this art and one can expect a general, decline in craftsmanship in later periods. Dating jewelry mosaics can be extremely difficult and the mountings are usually the best clues when maker’s marks or provenance papers are absent.

Micromosaic

Micromosaics are characterized by the use of small cubes or rectangles, named “tesserae” (from Latin, plural of tessera meaning “having 4 corners”). These tesserae can be from metal, marble or any hard stone, but are mainly made from glass rods which are cut with a blade and hammer and termed smalti. The colors of these smalti are almost limitless and are produced in Venice. The smalti which are produced in bi-colors are named millefiori (“1000 flowers”).

The technique of creating these mosaics involves not only a steady hand and some artistic skill, but more importantly one needs to exert much patience to place these glass tiles in place. With smalti sizes as small as 1/10 of mm. One can easily imagine the design taking a few months to longer to complete. A layer of cement was placed on a metal back and left to dry, after which the design was drawn on the cement. The cement was then carved to accommodate the small tesserae, which were then individually placed in the channels with some adhesive.

Another method involved keeping the smalti longer and trimming them down to the desired height after the design was worked out6 much like Persian rugs are scissored down after looming.

In jewelry these minor opus vermiculatum mosaics were mainly created from around 1810 – although it started in the 1770s when Giacomo Raffaelli created a brooch with a copy of the doves of Pliny7 -with a rise and fall in the decades leading towards 1850. It was estimated that there were some 150-200 workshops in Rome creating these mosaics around the latter date and there was a general decline in workmanship around the mid-19th century. Around 1850 the Roman jeweler Castellani, inspired by his friends Count Olsoufieff and Duke Michaelangelo Caetani,8 introduced a new style of mosaics for jewelry which utilized golden barriers in the designs, much like champleve enamel, and his creations were of such high quality that it gave a new incentive to the industry as well as drawing the attention of the beau monde. Castellani’s motives were inspired by Early Christian mosaics and archaeological finds. Although the mosaics were created under Castellani’s supervision, they were fabricated at the workshop of Luigi Podio,9 with whom he had a lifetime commitment.

Other 19th-century motifs found on micromosaics from Rome include the Pliny doves, portraits, Roman buildings and ruins, mythological Gods and creatures as well as flora and fauna. From Switzerland came micromosaics with mainly floral and landscape depictions. Another, small, center for micromosaic production was in Naples.10

After the micromosaic was finished, it was incorporated in jewelry, usually in a brooch, pendant or en esclavage necklace. Sometimes the micromosaic was inlaid in a black marble – or glass – surface as usually done with pietra dura mosaics.

Pietra Dura

In 1588 Grand Duke Ferdinando I de Medici founded The Opificio delle Pietre Dure (originally named Galleria di’Lavori11 a Florentine workshop which created furniture and other items inlaid with a parquetry or marquetry of hard stones. This descendant of the opus sectile style later became known as pietra dura (from Italian: “hard stone”). Although its roots date back to Caesarian Rome12 and was revived during the Renaissance, jewelry of this type did not emerge until the 19th century.

Although the pietra dura mosaics resemble micromosaics at first glance, the technique is very different. While micromosaics are an early type of pointillism, the pietra dura technique bears more of a resemblance to a jigsaw puzzle. Carefully selected hard stones – such as marbles or gemstones – are cut in slabs and then shaped into a desired form by means of sawing, cutting, and/or grinding according to a design. Afterward, these calibrated pieces are embedded in a slab of black marble, or – in later periods – in black glass. This technique does not only require that the individual pieces of the puzzle are fitted together very tightly, but also that the background – in which it is embedded – is carefully crafted as a close-fitting negative of the contour. Most mosaics of this type are multi-colored images against a dark – either marble or glass – background and are then set in a jewelry item. The motives have a wide range, but mainly they are of floral design.

Most pietra dura mosaics are embedded in a background of marble, or glass, and the stone serving as the background needs to be chiseled with high precision to accommodate the shaped hard stone slabs. It has been said that sometimes drops of acids were employed to create the bedding.13 Another way of creating pietra dura mosaics was without a visible ground,14 where the calibrated stones were put together and held only by a cement instead of in a background as one usually encounters.

The quality of these items lies in the finesse of the work and the mount it is in. Coarser items were created towards the end of the 19th century and they usually are of very low value.

Sources

- Wyatt, Digby. Architect. On the art of Mosaic, Ancient and Modern. Meeting Feb. 3rd 1847, Royal Society of Arts. Published in Transactions of the Society of Arts for 1846-7, Johnstreet, Adelpha, London.

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History.

- Soros, Susan Weber & Stefanie Walker, ed. Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Untracht, Oppi. Jewelry, concepts, and technologies. New York City, USA: Doubleday, 1985.

- Bennett, David & Daniela Mascetti. Understanding Jewellery. Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991.

- Huibers, Jef. Twee eeuwen sieraden. Schoonhoven, The Netherlands: De Vakschool.

- Amstel-Bos, E.G.G van. Sieraden uit de negentiende eeuw. Lochem, The Netherlands: De Tijdstroom, 1981

- Chadour, Anna Beatriz and Rüdiger Joppien. Schmuck I, Kataloge des Kunstgewerbemuseum Köln – band X. Köln, Germany 1985

- Möller, Renate. Schmuck. Munich, Germany: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1998

- Romero, Christie. Warman’s Jewelry. Iola, WI, USA: Krause Publications, 2002

Notes

- Esther 1:6.↵

- Wyatt, p.18.↵

- Pliny, chapt. 36:60.↵

- Xerxes ruled from 485-465 BC.↵

- according to Wyatt, p.18-19, based on the works of Giovanni Giustino Ciampini (Vetera monimenta in quibus praecipua … musiva opera .. illustrantur – 1690 and 1699)↵

- Untracht, 593↵

- or at least it is one of the first known jewelry artifacts of this type.↵

- Soros, 157.↵

- Soros, 159.↵

- Romero, 66-67.↵

- OPD website↵

- Wyatt, 19.↵

- Literature on this is absent↵

- Untracht, 594-5↵