Historical Perspective

The Wiener Werkstätte had its roots in a combination of key events in the lives of its founders, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, and the storm of change that was sweeping through the field of decorative arts during the fin-de-siècle. In Great Britain, the Arts & Crafts movement laid the groundwork for a collaborative guild-style creation. The Art Nouveau movement, embraced by much of Europe, was taking design in a totally new direction, throwing out the conventional and embracing the idea that design and creativity, not intrinsic value, should inspire design. In Germany, where Art Nouveau was known as Jugendstil, they added another dimension to this effusion of change. Initially mimicking the flowing lines of French Art Nouveau, they were soon putting their distinctive stamp on the design revolution by adding geometric shapes and forms that were more abstract, a preview of the upcoming Art Deco period.

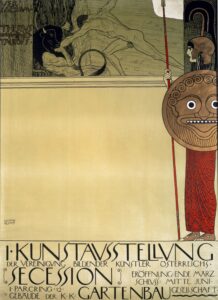

This evolution continued through the Vienna Secession, founded in 1897, which advocated the philosophy that the fine and decorative arts were to be valued equally. Exhibitions were held by the Secession in order to showcase their artistic concepts in which their beliefs were demonstrated by inter-mingling their displays. Paintings, furniture, jewelry and household items were not pigeonholed but shown together as a total artistic look (Gesamtkunstwerk) encompassing the home and the homeowner. Fashion, jewelry, and accessories, furniture and décor were all included in the “fine arts” alongside more recognized artistic endeavors such as painting and sculpture. They were all imbued with beauty regardless of their function.

Late in 1900, an exhibition was held that featured works by the Viennese Secession alongside a large collection of decorative arts, paintings, and sculptures from other European countries. A room completely built, designed and furnished by the “Glasgow Four” was a highlight of the exhibition. A fortuitous side benefit of their participation was the forging of an important bond between Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, James Herbert and Frances MacNair and two of the Secession founders, Hoffmann and Moser. Influencing Moser in particular with their use of a unique color palette and “dreamy” motifs, the Mackintosh’s friendship was a critical catalyst for the formation of the Wiener Werkstätte.

Charles Robert Ashbee and the Guild of Handicraft were also a significant presence within the exhibition having a bold display in the main hall. Moser and Hoffmann took inspiration from Ashbee’s view of functional items as objects of beauty whose purpose goes well beyond mere function to adornment. The role of the worker in crafting their designs was another innovation Ashbee brought with him to Vienna. The idea of the craftsman as a valued member of the design production team was a new one and an eye-opener to the Secession members.

Wiener Werkstätte

An eventual rift between craft-oriented Secessionist members – “stylists” – and the traditional “naturalist” artists resulted in a break by the “stylists” and the formation of the Wiener Werkstätte.

The aim [of the Guild] is the promotion of the economic interests of its members by training and educating them in handicraft, by the manufacture of craft objects of all sorts in accordance with artistic designs drawn up by the Guild members, by the construction of a workshop, and by the sale of the goods produced.1

With this statement of purpose, the Wiener Werkstätte was formally established on May 19, 1903. There were six original members: Hoffman and Moser, cooperative directors; Waerndorfer, treasurer; Karl Kallert, silversmith; Konrad Koch and Konrad Schindel, metalworkers.

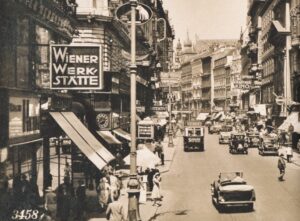

Quickly outgrowing their original site (in only a matter of months,) they moved to Neustiftgassse and a large three-story facility. This expansion accommodated not only jewelry but bookbinding, leatherwork, woodwork, lacquer work and an architectural office. There was exhibition space, offices and a chance to showcase their Gesamtkunstwerk philosophy claiming to be able to design, furnish and accessorize “complete houses” with the products of their Werkstätte. Clean, well-lit workshops provided good healthy conditions for the craftsmen. More space meant more artisans and among the first to be hired were Josef Hossfeld and Eugen Pflaumer, both master metalworkers.

Ashbee’s Guild of the Handicraft was regarded as a model for workshop design addressing the goal of collaboration between artists and craftsmen. The role of Ashbee’s Guild was to provide a way to better the quality of life for guild workers while enriching the customers with their beautiful and functional designs. Items produced by the guild were to be available to people in every social stratum, i.e. design for the masses.

There were major differences between Ashbee’s philosophy and that of the Wiener Werkstätte’s. The foremost difference lay in the fact that Ashbee’s workers were trained on the job while the Werkstätte hired craftsmen already formally trained. The Wiener Werkstätte’s philosophy embraced the idea that fine craftsmanship came at a premium and did not need to be available to the less-than-well-to-do, so the additional expense of formally trained workers was seen as a necessity. Also, outside manufacturers were available to bring their work to fruition and the ”Werkstätte” did not eschew the use of machinery in the workshop.

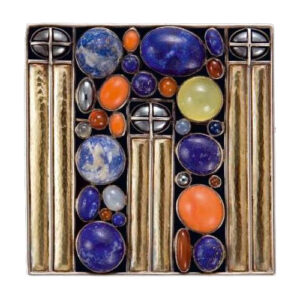

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

c. 1908.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Wishing to reflect societal change without resorting to a recycling of the designs of their predecessors, the founders of the Wiener Werkstätte endeavored to court clients who embraced their philosophy of enriching all aspects of life through creating beauty in everything that surrounded them. Much of the work produced at the Wiener Werkstätte was embraced by the Viennese elite, traditional supporters of the arts. Clients ranged from those desiring a few “contemporary” items to complement their décor to those who fully embraced Gesamtkunstwerk designing and furnished their homes entirely from the Wiener Werkstätte.

Jewelry clients often wore their jewels as an outward symbol of their independence and in this way served as unofficial advertising to spread the word about the Wiener Werkstätte. Getting the word out about this new concept was also facilitated by the publication Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration. It became the exclusive outlet for the documentation of the Wiener Werkstätte and all of its products. They beautifully photographed and documented each item and, in the case of the jewelry, the pictures included the handmade fitted leather box that accompanied each piece.

We wish to establish intimate contact between public, designer and craftsman and to produce good, simple domestic requisites. We start from the purpose in hand, usefulness is our first requirement, and or strength has to lie in good proportions and materials well handled… The work of the art craftsman is to be measured by the same yardstick as that of the painter and the sculptor… So long as our cities, our houses, our rooms, our furniture, our effects, our clothes and our jewelry, so long as our language and feelings fail to reflect the spirit of our times in a plain, simple and beautiful way, we shall be infinitely behind our ancestors.2

Clients

It took more than mere publicity to propel this modern philosophy of the decorative arts to the forefront; it took clients wealthy enough to indulge themselves in the vision of the Wiener Werkstätte.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

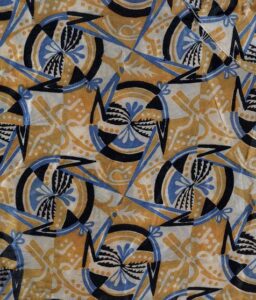

The most famous clients of the Wiener Werkstätte were Gustav Klimt and his friend and muse, Emilie Flöge. Klimt had been a member of the Vienna Secession and was very familiar with the members of the Werkstätte and their philosophy. Flöge used the Wiener Werkstätte to design the interiors and furnishings for her avante-garde dress salon, Schwestern Flögewhere jewelry from the Wiener Werkstättewas well represented. Many, if not all, of the fabrics used to create the “reformer” dresses sold by Flöge, were designed and produced at the Wiener Werkstätte. Women wearing these “reformer” fashions also figure prominently in Klimt’s iconic portraits.

Other major clients fall under the umbrella of “investors” based on the scope of their involvement. Fritz Waendorfer and his wife Lili completely remodeled their home using the Wiener Werkstätte to design, create and fill the space. Their commitment to Gesamtkunstwerk was so complete that they exhausted their vast fortune in order to achieve it.

Otto and Eugenia (Mada) Primavesi came along just in time to provide much-needed financial support to the Wiener Werkstätte. They built a country house with Hoffmann as their architect and designer. Otto died in 1926 and Mada’s fading wealth forced her to withdraw support for the Wiener Werkstätte in 1930. Efforts to replace these essential financial supporters were unsuccessful and combined with the changing “air” in Europe, the firm closed in 1932.

Jewelry

Jewelry was conceived to feature the designer’s artisanship along with the craftsmen’s skill, creating jewels as art with a goal of adorning the wearer. Gone was the notion of jewelry as status symbol and, as a result, a wide range of materials became available as a palette for the designer including beaten silver, copper, and some gold. Cabochon-cut gems were used extensively, collet-set in repoussé and wirework, and valued for their color and not their price. No longer was there a total reliance on diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires to create jewels. Adorned with these miniature works of art, the wearer was seen as artistic and sophisticated. Simply put, the value was in the artisanship, not the materials.

Brooches, hat pins, hair combs necklaces, and belt buckles were designed with an outer framework, often rectangular, with various design elements within. While the outline was severe, the more intricate interior elements could be quite sensuous with undulating tendrils, flowing flowers, and sinuous leaves. Riotous color was provided by the myriad of cabochon gems bezel set within the designs. Sometimes a single focal gem would punctuate the piece. Gold or gilt accents and enamel were also used to provide contrast to the work. This style provided a good deal of negative (open) space to allow the wearer’s garments to show through providing additional interest and color. Elongated rectangular bar brooches, square plaque de cou, and other necklace elements were also subject to this design criterion.

Photo Courtesy of Doyle New York.

Pendants on the other hand often had a more organic shape. While still designed as a “frame” with internal elements, the frame itself was not limited to a strict geometric outline and many had curving “brackets” that formed the outline. Inside were floral and foliate motifs with sinuous movement, much like the brooches and again enhanced by multicolored cabochon gems. Oval link chain provided the support for the pendants and was often swagged or pinched together just above the pendant and accented by another small plaque or gemstone.

Bracelets and belts reflected the same aesthetic as brooches and belt buckles, with repetitious construction. Framed design elements were linked together like so many brooches all in a row. A few were designed as a more randomized conglomeration of rectangular and square-shaped elements, often bezel set with gem materials.

Jewelry is often marked with the Wiener Werkstätte registration mark, along with both the artist and the craftsman’s monogram emphasizing the importance of all three. Moser designed the monograms to be used by artists and artisans to mark their work- square-shaped for the artists and circular for the craftsmen. While distinctions as to their “duties” were carefully delineated everyone’s contribution was valued.

Principal Designers

Principal designer Josef Hoffmann came from an architecture background but soon branched out to embrace all forms of the decorative arts. His jewelry favored compartmentalized gemstones within a square frame much like a miniature painting colored by gem material instead of paint. His early designs were very geometric with square and rectangular divisions along with architectural elements such as pillars. Using graph paper to conceptualize his designs (much like miniature architectural plans,) the craftsmen then executed the finished jewel from his exacting illustrations. Each and every component was hand constructed, but the end result, with all its geometry, had a machine-made feel.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Some interplay of design between Gustav Klimt and Hoffman can be seen in shapes found in the jewelry elements used in Hoffman’s designs and repeating patterns in Klimt’s paintings. This would suggest, at the very least, that these men may have worked collaboratively or their proximity may have provided opportunity for inspirational influence between them. Indeed, Klimt’s designs show up in many of the installations by the Wiener Werkstätte. Circa 1908 Hoffmann’s style begins to undulate a bit and depart from the severely geometric works produced previously. The style of the day had crept into his designs and they became more variable with some sensuous elements.

Koloman Moser began his career as a graphic illustrator and these roots provided a springboard to his inevitable success as a designer of decorative arts. His work reflects the Arts & Crafts aesthetic, the Jugendstil and his personal preference for themes from nature. Combining these natural motifs with a design sensibility that was meant to enhance the wearer of looser, more flowing clothing resulted in a series of pendants dangling from long chains. Moser resigned from the Werkstätte in 1907 reportedly over money issues.

Designers

Carl Otto Czeschka studied to be a painter, joining the Wiener Werkstätte in 1905. Czeschka’s jewelry was ethereally constructed from his nature-inspired designs with many of the construction details spelled out in minute detail for the craftsmen. In 1907 he was awarded a professorship at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Hamburg, continuing to design for the Werkstatte through 1909.

A former student of Hoffmann’s, Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill joined in 1907. He quickly became the head of the fashion department, developing a clothing style apropos of one who lived in a Wiener Werkstätte home. Jewelry was an important part of this amalgamation and his foliate-inspired designs were usually rendered in gold or platinum. Wimmer-Wisgrill left the Werkstätte in 1922.

Dagobert Peche was an architect who was versatile in most of the applied arts and initially freelanced his designs for the Wiener Werkstätte. Jewelry was his passion and he designed each piece as one would a sculpture, taking into account every conceivable viewing angle. He worked in a more traditional style favoring mythological themes and figures along with foliate motifs for his subjects. Shortages resulting from the war inspired the creative use of unusual jewelry materials and many of Peche’s works were rendered in carved ivory by master craftsman Friedrich Nerold. From 1917-1919 Peche directed the short-lived Wiener Werkstätte established in Zurich.

Goldsmiths

Silversmiths

Metalsmiths

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Staggs, Janis, Editor. Wiener Werkstätte Jewelry. (Neue Galerie: Museum for German and Austrian Art.) Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2008.

- Zorn Karlin, Elyse. Jewelry & Metalwork in the Arts & Crafts Tradition. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 1993.

- Koloman Moser & Josef Hoffmann, 1905 Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration XXIII, 1913-14 translated from German by Gabriele Fahr-Becker.