This little perfect figure may seem to be a trifling matter on which to found an essay; and yet we shall find it connected with history and poetry. It is indeed, a small link, although it has bound together millions for better for worse, for richer for poorer, more securely than could the shackle wrought for a felon. An impression from it may have saved a or lost a kingdom. It is made the symbol of power; and has been the mark of slavery. Love has placed it where a vein was supposed to vibrate in the heart. Affection and friendship have wrought it into a remembrance; and it has passed into the grave upon the finger of a loved one.1

In existence for over six thousand years, rings appear in almost every culture of the world. In addition to satisfying purely decorative needs, rings have served a multitude of purposes, both practical and symbolic. Rings have been used to pledge one heart to another, to seal correspondences and authenticate documents. They have served to memorialize a friendship, honor the dead and as talismans to provide protection against the forces of evil. Rings have also been used as symbolic expressions of faith or as tangible evidence of power and wealth. So ubiquitous an item, rings of all periods have survived providing valuable historical insight into various cultures and as a timeline of major design themes and materials in jewelry history.

Ancient and Classical Rings

Ancient Egyptians are known to have worn scarab rings, carved from a variety of stones including lapis lazuli, amethyst, rock crystal and turquoise, threaded simply by a silver or gold wire. They were often engraved on the flat side of the scarab with decorative hieroglyphs, protective symbols, or titles; with a simple swivel, the function of both signet and amulet were combined. During the period of the New Kingdom, (1559-1085 B.C.) Egyptian goldsmiths had progressed to casting all metal stirrup-shaped rings bearing the royal cartouche. These rings served not only as visible symbols of rank and power but as means to authenticate documents. Egyptians wore rings as signets or for religious and talismanic purposes and, although the materials were carefully worked and pleasing arrangements of stones and designs are evident, they were worn for a purpose rather than as mere decoration.

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection

The ancient Greeks and Romans wore rings for a variety of different purposes, including purely ornamental ones. Scarab rings were worn by the Greeks as were signet rings engraved with motifs from nature and figures from mythology and literature. Bezels set with gems prized for their beauty, rarity and talismanic properties were worn, as were plain gold rings. Rings could also be ornately worked in wire, filigree and intricate pierced work, (opus interrasile).

In early Rome, during the Roman Republic, the first rings were made of iron and served as seals. The right to wear gold rings, the jus annuli aurei, was at first accorded only to senators and only while serving as ambassadors of the Republic. In time the right to wear rings of gold was awarded to all civilians. During the later years of the Roman Empire, both men and women came to wear heavy gold rings set with rare and costly gems in ever more conspicuous displays of wealth and status. While it had once been rare to wear more than one ring, by the first century AD each finger might be laden with multiple adornments.

The Greeks used rings as tokens of affection and love, frequently engraved with appropriate symbols such as depictions of Eros or Aphrodite. The custom of exchanging rings as tokens of betrothals, however, is believed to have originated with the Romans. Jewelry historian Diana Scarisbrick writes:

Since it was customary to exchange rings to mark the agreement of a business contract, so a ring, the annulus pronubu, was given as a pledge of engagement to marriage-though, unlike the wedding rings of later periods, it did not signify that the union was permanently binding. According to Pliny this ring was originally of iron without a gem, but by the 2nd century AD all who could afford to use gold did so.2

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Roman wedding rings often featured the image of two right hands clasped in symbolic representation of marriage and fidelity called dextrarum iunctio in Latin. In Roman symbolism, the right hand was considered sacred to Fides, the deity of fidelity – the motif reappears in the Middle Ages as the fede ring. According to ancient texts, the betrothal ring was worn on the fourth finger of the left hand in the belief that this finger had a vein, the vena amoris that flowed directly to the heart. Another motif used for betrothal rings was the marriage knot or knot of Hercules, a simple and symbolic design of two intertwined ropes that is probably the origin of the phrase “tying the knot.”

Perhaps the ring style most associated with the Romans was the signet ring. Diana Scarisbrick notes that the wealth of Rome attracted the best and most skilled artists to engrave and set gems. Signet rings were used to seal official documents, with gemstone intaglios frequently engraved with the wearer’s portrait. They were also worn for purely decorative purposes and were often large and ornate. Aspects of everyday life, figures of gods and rulers and portraits of poets and philosophers were among the popular themes. Love was another favored theme and intaglios featuring the heads of lovers face to face were used in signet rings as marriage rings.

Rings of the Middle Ages

Photo Courtesy of the Schmuckmuseum.

The most widely worn piece of jewelry, both by men and women in the Middle Ages was the ring. Decorative and easily worn, hands were often heavily bejeweled with each finger, including the thumb, adorned with several rings on different joints. Rings were sometimes worn in a variety of other ways as well; suspended by a cord or ribbon worn round the neck or tied round the arms, threaded onto rosaries or attached to a hat.3

This item is displayed in the Schmuckmuseum in Pforzheim, Germany.

By the mid-1300s ring wearing was such a symbol of rank in Europe that sumptuary laws were introduced in an attempt to regulate their wearing at appropriate class levels. Gold and silver rings set with precious jewels were to be reserved for royalty and nobility and base metals such as pewter, gilt bronze and the copper alloy, latten were reserved for those of more quotidian origins.

Decorative rings, during this time, were frequently made in a straightforward stirrup style in which a plain hoop inclines up to a bezel containing a gemstone. Most gems were cut en-cabochon until the fifteenth century and their uneven outlines were most easily set with a simple pronged claw setting or a collet setting pressed around the gem.

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

By the fifteenth century, settings had become more elaborate with a scalloped bezel surrounding the gem. This scalloped design was sometimes referred to as a “panse” by the English in reference to its flower like outline.4 The bezel was often supported by more decorative shoulders, worked with designs such as scrollwork, leaves, flowers, and dragons and embellished with niello and enamel. As for the gemstones themselves, they were chosen not only for their intrinsic value and beauty but also for the talismanic properties they were thought to possess. Direct contact of the stone with the skin was believed to amplify these medicinal or amuletic benefits and rings were particularly suitable in this aspect. The author Marian Campbell writes of a few of these properties that medieval lapidaries ascribed to certain gems including:

…sapphires could expel envy, detect fraud and witchcraft. Rubies were believed to promote health, dispel bad thoughts, reconcile discord and combat lust. Emeralds were thought to be a cure for epilepsy, helpful for eye troubles and for increasing wealth. And the turquoise was believed to guard against poisoning and to prevent falls when out riding. The diamond (which takes its name from the Greek adamas, meaning invincible or untamed) gave courage, as well as protection from nightmares.5

Surviving examples of medieval rings indicate that the most popular gemstones were sapphires, garnets, rubies, amethysts and rock crystal and to a lesser extent, diamonds.6

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Signet rings were used extensively during the Middle Ages in authenticating messages, sealing business documents and personal letters and as marks designating guilds and merchants. The intaglios carved by the ancient Roman and Greek craftsmen were particularly prized and spurred a revival in the craft of hardstone carving in the 13th century. Bezels and hoops were frequently engraved with the owner’s name and various phrases in Latin or French. Rounded capitals, known as Lombardic script, were used up to c. 1350 and from then until after 1500, the lettering used in inscriptions was in the spikier Gothic style of script. A significant development in signet rings during this period was the use of heraldry as a distinguishing design. The earliest examples are thought to be Italian but by the 15th century heraldic signets displaying coats of arms and other insignia were widely worn by all who were entitled to do so. A notable enhancement was the foiled crystal insignia in which the brightly colored coat of arms was painted underneath the engraved crystal keeping the colors intact when pressed into wax.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen.

The Middle Ages saw the flowering of chivalry and courtly love. Rings of friendship and love were popular and were frequently inscribed with sentiments of affection. The fashionable poesy ring was a hoop of gold with a short poem, a “poesie”, inscribed on the band in either Latin or more typically, in French, the language of romance. Many of the phrases are often repeated suggesting that jewelers carried an inventory of the more popular phrases. Some of the favored poesies include mon cuer avez (you have my heart), due tout mon couer (with all my heart), and amor vinicit omnia (love conquers all).

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

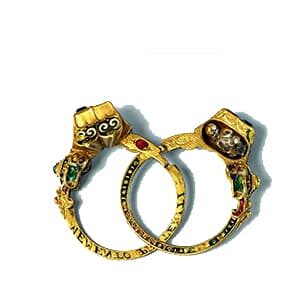

More elaborate versions were decorated with simple enameled designs of leaves, flowers and teardrops, expressive of tender emotions. Those with means also used gemstones, most particularly if the ring was to be used as a symbol of marriage. Another popular ring of sentiment during this era was the gimmel ring (from the Latin gemellus for twin) made of entwined double or triple hoops that represented the bonds of friendship and love. Believed to be French in origin, they were often combined with the fede motif of ancient Rome which had made a reappearance as a marriage ring as early as the 12th century in England. Another marriage ring that was created during the Middle Ages was the Jewish marriage ring. Most often made of richly enameled and filigreed gold, these rings sometimes featured fully dimensional miniature houses symbolizing the nuptial home or the Temple of Jerusalem. As such, they were reserved for symbolic use during the marriage ceremony being too unwieldy to wear on a daily basis.

Rings of the Renaissance

© Victoria & Albert Museum.

The Renaissance was the era of the goldsmith. In contrast to the relative simplicity of the Middle Ages, gold work during the Renaissance reached new levels of craftsmanship and design. As the art of sculpture and painting reached new heights of mastery, the jeweler’s bench was considered the best training ground to achieve the depth of detail and precision that characterized the era’s most accomplished artists. Indeed acclaimed artists such as the painter and sculptor Donatello, the painter Botticelli and the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini all trained as goldsmiths. This virtuosity was apparent in all types of jewelry but most particularly the ring. Influenced by the interest in sculpture and painting, rings were often decorated in arabesque motifs with sculptured shoulders of figural and floral designs and extravagantly enameled in increasingly sophisticated techniques including en ronde bosse.

© Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Bezels were of symmetrical quatrefoil or even multifoil floral design and often chased and enameled. Along with the more elaborate settings, another innovation was the hinged ring containing compartments for scented materials or even reliquaries. Perfume rings were a particularly useful design in counteracting the daily olfactory assaults of this period ( in another version they could also be used to conceal poison such as the rings that the infamous Borgias reportedly used to such ill effect.) Colored stones remained popular with all who could afford them and the most desired stones were ruby, sapphire, and emerald. Rings as in Medieval times were worn on every finger and on multiple joints. The high fashion of the late Renaissance included elaborate neck ruffs, large padded sleeves, and cuffs that limited the forms of jewelry that could be worn. Rings, on the other hand, were unencumbered by these fashions and could be freely enjoyed.

© The Walters Art Museum.

The more decorative Renaissance signet rings featured portrait intaglios of contemporary European rulers such as Henry VIII of England. Roman emperors and other classical subjects were even more popular themes and gems, either newly carved by masterful artists or preserved from antiquity, were greatly prized and set in highly sculpted and enameled settings. Heraldic signet rings of a more practical working nature tended to be set in simpler, more functional settings that were much treasured as heirlooms representing family lineage and bloodlines.

The bloodstone was deemed a particularly appropriate gemstone for this purpose. Signet rings featuring the marks of guilds or merchants were appropriately plain and serviceable for heavy use. Initial rings were also popular and were more elaborately designed with the initials linked by knots or forget me not flowers. In some cases, they were given as marriage rings with the betrothed’s initials entwined together.

Love and friendship rings retained many of the same themes and forms as from the Middle Ages albeit in more elaborately worked settings. Cupid with his bow and arrow and hearts are two of the familiar motifs used. More unusual was that of a stag eating dittany, a herb that was believed to cure wounds, including those caused by love’s arrow. Diana Scarisbrick also writes of the loyal and faithful dog, adopted as a symbol of fidelity between lovers. The posy ring now had its inscriptions, which were increasingly in roman capitals, hidden inside the band and was used as both a token of love and as a wedding band.

Photo Courtesy of the Schmuckmuseum in Pforzheim.

Gimmel rings, frequently decorated with a fede motif, had inscriptions both without and within the bands and more elaborate examples had three or more hoops that could accommodate longer inscriptions and more intricate designs. The more valuable gimmel rings featured gemstones either in contrasting or uniform color blocks and in rarer cases, memento mori figures were secreted within compartments beneath the stones.

Image Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, NL.

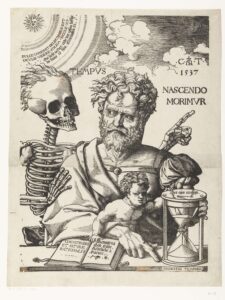

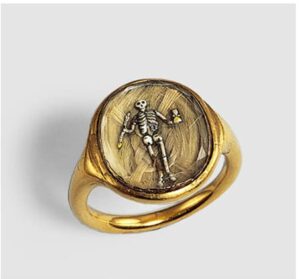

Reminders of impending mortality have long been a theme in jewelry, most particularly in rings. In the ancient world, such symbols as skeletons, skulls and most poetically, figures of cupid holding a symbolic torch of life upside down were commonly used. Aphorisms relating to the transient nature of life and its fleeting pleasures usually accompanied the imagery. The Middle Ages infused memento mori themes with an emphasis on living a just and moral life in anticipation of divine judgment. The Renaissance continued in this tradition and rings were decorated with coffins, skeletons, hourglasses and most frequently, skulls. During the Renaissance, memento mori themes were also used in signet rings, some with bezels that rotated from intaglios to a death’s head, and wedding rings with both fede and memento mori motifs have been found. Diana Scarisbrick describes one particularly imposing 16th century ring:

The most elaborate surviving example has a locket bezel in the form of a book, the cover centered on a skull midst toads and snakes, recalling the biblical quotation ‘For when a man is dead he shall inherit creeping things, beasts and worms’. Inside appropriate quotations from the Bible are inscribed on the back of the lid, above a sleeping child, an hourglass and a skull 7

Seventeenth Century Rings

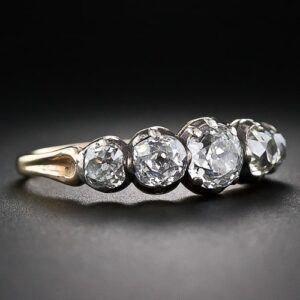

Toward the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth century, a marked change in jewelry and ring styles took place. Just as the Renaissance period was highlighted by ornate gold settings this era was distinguished by a growing emphasis on the gemstone. Refinements in cutting and foiling techniques resulted in a greater diversity of shapes and an emphasis on displaying the beauty of the gems themselves. Enamel is now typically used only as an accent in either white or black and, while gold is still used for colored gemstones, diamonds are set off in silver. Large stones are now worn and set as solitaires while arrangements of smaller stones are set in a myriad of shapes including stars, rosettes, and cruciforms. Details on the shoulders are kept subdued and most often as an engraved foliate motif simply enhanced by black and white enamel.

Photo Courtesy of the Schmuckmuseum.

The prevalence of death was an inescapable part of everyday life in the 1700s. Continued plagues, widespread poverty, famine, and war – all these Malthusian factors served to keep death a common presence and the wearing of memento mori rings popular. A variety of ring styles were used with memento mori themes including signets, wedding rings with a skull between two hands, and locket rings featuring skulls and crossbones. As with other rings, gemstones if affordable, added an element of less austere ornamentation.

By the second half of the seventeenth century, memento mori imagery began to merge with the mourning ring. Distributed according to wills, seventeenth-century mourning rings were inscribed with details such as the individual’s name, initials, coat of arms and date of death. A plain gold band or band of gold enameled all the way around in emblems of death and burial, with an inner inscription was characteristic. Locks of hair were sometimes contained in locket bezels or in hollow hoops. The increasing popularity of bequeathing mourning rings is generally attributed to the execution of the English King Charles I in 1649. Supporters of the monarchy wore jewelry, most often rings, made of a flat-topped quartz crystal that covered a gold wire cipher or crown set upon a background of plaited hair. This style known as Stuart Crystals would continue to be popular into the 18th century.

Eighteenth Century Rings

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Jewelry of the Georgian era was light, elegant and refined. Indicative of the rococo style, rings worn by day often featured delicate combinations of colored stones, many in bright asymmetrical giardinetti bouquets or elegant ribbon and bow designs supported by gracefully divided shoulders.

In a tribute to popular pastimes, rings were also designed as hands of enameled playing cards, fancy dress masks or even musical instruments.

The more formalized neoclassical influences of the latter 1800s led to a return of symmetrical settings and elongated bezels in a myriad of shapes including oval, navette, lozenge and octagonal.

These larger bezels frequently supported larger single stones surrounded by frames of coruscating diamonds or pearls. Others were more simply flanked on either side by a pair of rose or brilliant cut diamonds. Featured stones were frequently either semi-precious or paste, affecting an opulent look at a much more reasonable cost. It should be noted that paste jewelry was respected in its own right and carried by the finest jewelers of the day.

Stone settings progressed from enclosing the underside of the stone from the girdle down to a lighter, narrower collet setting. Castellated collets imbuing the piece with a more refined and delicate appearance were a further innovation. In more expensive pieces, attention was also given to the underside of the setting with ribbing detail on the backside that gave a more polished and detailed finish to the piece. While most gemstones were still foiled and backed to enhance color and brilliance, a greater understanding of the mechanics of light dispersion led to open back, à jour settings, on finer gemstones.

Rings were usually crafted in 18 or 22 karat gold while silver or silver- topped gold was used for diamond mountings. In many cases, the backs of silver-mounted diamonds were foiled and covered in an additional layer of gold to prevent tarnish markings. Pinchbeck, a widely used gold imitation of the time was also used. Popular gemstones of the era, besides diamonds, included: rubies, emeralds, sapphires, amethysts, garnets, pink topaz, turquoise, and opal as well as shell, coral, and mother-of-pearl.

Photo Courtesy of Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Known as the age of enlightenment, the eighteenth century’s neoclassicism had its roots in the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome. The ardor for the classicism of the past was fueled in part by the tradition of sending the sons of the wealthy and well-connected on what came to be known as “the Grand Tour” of Europe. Inspired by the artifacts of Rome and Greece many began collecting antiquities including intaglios and cameos inspired by or fabricated in ancient Greece and Rome.

Once again, signet rings became a popular adornment and reinvigorated the art of gem engraving, particularly in Rome. A wide range of subjects including details of ancient cities, sculpture, contemporary rulers, military heroes and popular authors were chosen as subjects for signets. While there were always exceptions, the most common setting was a simple oval or round bezel in the spare elegant Roman style.

© Victoria & Albert Museum Collection

Such was the demand for and cost of these pieces that replicas of ancient engraved hardstones and gemstones became quite popular. The most well-known and finely manufactured of these were made in London by James Tassie. Made of paste that could simulate all manner and colors of gem material, over 15,000 reproductions of both modern and ancient gems were produced. While some signet rings were still worn for practical purposes, the emphasis was now firmly on effect and style.

Romantic Rings

The Georgian era covering the years between 1714 and 1830 was very much associated with a spirit of romance and the celebration of the bonds of friendship. Fede and gimmel rings were still popular as was the closely related Claddagh ring featuring a single bezel of two clasped hands holding a heart surmounted by a coronet.

The heart motif was by far the most highly used symbol of love during this era which included many other insignias such as lover’s knots, keys and padlocks, turtledoves, flaming torches, putti and wishbones. Hair was also a common element in many rings of sentiment. The plaited locks of a son or daughter or grandchild as well as those of a wife or lover were incorporated into rings in a variety of methods: woven into ciphers, secreted in glass compartments, braided into bezels and combined with portrait miniatures.

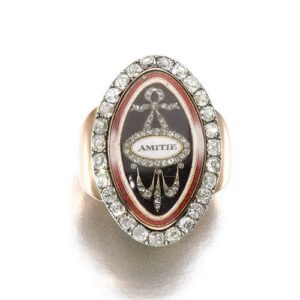

In keeping with the era’s more playful characteristics were regard rings, first introduced by the French firm Mellerio in 1809, which used the first letter of the gemstone to spell out affections such as ADORE (Amethyst, Diamond, Opal, Ruby. Emerald). French was still the language of love, used in poesy rings and in the visual and phonetic puns of rebus rings which used pictures and words to express a sentiment. Pense de moi (think of me) was represented by an enameled pansy followed by the letters LACD which phonetically translates to Elle a Cédé (she has yielded). After 1770 the style of elongated bezels supported more elaborate tableaux that could combine several different symbols.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Marriage rings of this era ranged from plain gold or silver gilt bands to the increasingly popular diamond ring. Frequently a pair of keeper rings, usually of narrow diamond hoops, was worn on either side of the wedding ring to keep it secure. By the 1800s, a diamond became the most common betrothal ring; the keepers evolved into the simple wedding band that is traditionally given during the marriage ceremony. The wedding ring was now traditionally worn on the ring finger of the left hand and it was also customary for men to wear a ring.

In France, the marriage ring, known as the alliance, was inscribed with the dates and initials of the couple and was frequently accompanied by the piece de marriage – a medal that also contained the married couple’s initials and marriage date. A favored theme of the alliance was the romantic design of twin gemstone hearts, sometimes pierced by cupid’s arrow or united under graceful girandoles. Another custom of the day was to present a ring with the bride’s new cipher to mark the change of her name to that of her husband. Diana Scarisbrick notes:

It was also customary for a bride to receive at the wedding a ring with the initials of her new married name, at first executed in rose diamonds in an open work bezel and, in the second half of the century, often elaborately intertwined applied on a dark blue background.8

Memorial Rings

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

This item is displayed in the Schmuckmuseum in Pforzheim, Germany.

Memorial rings reached their height of popularity in the eighteenth century. By far the most popular form of mourning jewelry it was common to make provisions in wills to distribute them to an ever-widening circle of family, friends, and acquaintances.

A typical mourning ring of the mid 18th century featured a gemstone or crystal bezel, some in the shape of a coffin, and the name and dates of the deceased engraved on enamel or gold bands. Under the crystal bezels, images of skulls and crossbones were frequently mounted on silk or hair and the more extravagant examples had diamonds at the shoulders. Simpler bands engraved with aspects of death and burial were also distributed with an inner inscription of pertinent details.

As the century progressed, the more romantic influences of French design prevailed and images shifted away from the stark reminders of mortality to an emphasis on representing death and mourning more symbolically. The inscription moved to the outside of the band replacing skulls and skeletons with lettering of raised gold against a background of black or white enamel.

Photo Courtesy of The Walters Art Museum.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

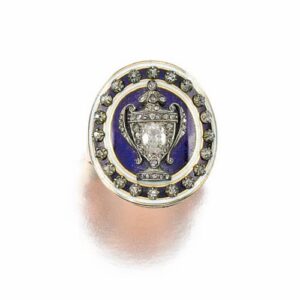

The color white signified the death of a child or an unmarried individual; an all too common occurrence. The Neoclassical designs of the later 18th century were more elaborate and allegorical in their design themes. Mourning rings of this period were larger, featuring oval, marquise and oblong bezels decorated with mourning miniatures. These frequently featured scenes incorporating such symbols as broken columns of Roman and Greek ruins, weeping willows, funeral urns, and streams representing eternity.

Hair was sometimes incorporated into the making of the pictures directly, either ground to make up the paint itself or using single strands to form images such as the branches of a weeping willow. Other mourning rings prominently featured elaborately plaited or braided hair under a glass locket. Frames were often classically plain although borders of pearls (representing tears), diamonds and enamel were also widely used. The most extravagant memorial rings, reserved for those of rank and high social standing could be quite sumptuous with rings featuring heraldic enameling or deep blue guilloche enameling surmounted by diamond funerary urns and diamond framing.

Related Reading

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery. Second Edition. Colchester, Essex: N.A.G. Press Ltd, 1987.

- Bury, Shirley. Victoria & Albert Museum: An Introduction to Rings. Owing Mills, Maryland: Stemmer House. Publishers, Inc., 1984.

- Campbell, Marian. Medieval Jewellery in Europe 1100-1500. London: V & A Publishing, 2009.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington & Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery 1714-1830. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Edwards, Charles. The History and Poetry of Finger-Rings. New York. Redfield, 1855. LaVergne, TN. Kessinger Publishing’s Legacy Reprints, 2010.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Rings: Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd., 2007.

- Tait, Hugh, Editor. 7000 Years of Jewellery. London: British Museum Press, 1986.