Enameling is a decoration technique in which a glass of certain composition is fused to the surrounding or under laying metal. Although the exact origins are unknown, the art of enameling has been practiced since ancient times. Excavations on Cyprus – in the Mediterranean – in the 1950s unearthed the earliest known examples of cloisonné enameled jewelry, dating from the 13th and 11th century BC.

Although the ancient Egyptians decorated their royal artifacts with an ascendancy of colored gemstones, glass and faience, this was not an enameling technique but rather a form of mosaic. Early Roman enamels were also of this type where they used pieces of multicolored glass (“millefiori“) and placed them in a predestined pattern. The gaps in between were filled with a glass powder which, after heating, fused the millefiori smalti together. Though this is similar to enameling, the glass did not fuse to the metals. It was only later when they started to place the smalti in a type of tube setting and then punched the metal over the glass, followed by careful heating that caused a fusion to the surrounding metal, that we can speak of true enamel.

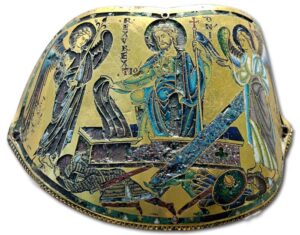

During the Byzantium era cloisonné enamel flourished in the Eastern Roman Empire as well as in many Celtic areas (as Gaul and in Britain). This technique has been known for over two millenniums and it could well have spread over Europe during the migration period which preluded the middle ages.

Champlevé enamel (also known to the Celts) reached its zenith during the 12th century in the Rheno-Mosan region and Limoges (France). Probably due to economic considerations, this technique was employed on copper or tombak plates instead of on the precious metals prior to that date. The workshops in Limoges almost completely switched to the technique of émail peinture at the end of the 15th century which become their trademark.

Due to the discovery of gums that could hold the enamel prior to heating – without leaving remnants after firing – the art of émail en ronde bosse became available during the Renaissance.

By the 18th century, the taste for enamel had almost completely disappeared – with the exception of painted enamel – only to be revived again in the 19th century with its heyday during the Neo-Renaissance and Art Nouveau periods.

Enamel is often also written as email or émail and one can easily see the resemblance with the more modern abbreviation for electronic mail. The latter should, at least by jewelers, better be written as e-mail to avoid confusion.

Technique

Enamel is a type of allochromatic glass that consists usually of quartz sand, iron oxide, potassium oxide (potash) and borax (flux). These components form a transparent and colorless fondant after firing at temperatures between 700 and 900 degrees Celsius. Their plethora of colors are established by the addition of different metal oxides and/or chlorides. After thoroughly crushing and washing these materials a hydrated mass is formed (a fondant) which is then applied on a suitable, and completely clean metal (typically gold, silver or copper alloys).

The choice of materials (metal and fondant) is dictated largely by the thermal expansions of these materials. When the thermal expansion of the metal and the fondant has a too large interval, the result is normally cracking and/or peeling off of the vitreous surface and the enameling process needs to be restarted with more suitable components. A skilled enameler will try to avoid this at all costs by careful experimentation. Sometimes the reverse of the work needs to be enameled as well to prevent warping of the metal, this is termed contra-enameling.

After the hydrated fondant is applied to the metal it needs to dry. Next, the work is placed in a furnace or kiln at the appropriate temperature. When after a few minutes the fondant starts to flow and shows a vitreous surface, the work is taken out of the furnace and left to cool. During this cooling, the enamel may shrink and resulting gaps will need to be filled again, after which the fore-mentioned process is repeated.

When the enameler is content with the result, the enamel is finished with a carborundum file and polished. This polishing is done either by hand or by placing the end result back into the furnace just long enough to regain a vitreous luster. In the former polishing method, a more controllable, or flatter surface is obtained.

Enamel comes in different degrees of diaphaneity:

- Transparent

- Opalescent (translucent)

- Opaque

Different metals may require fondants of specific transparency due to the reflectance of the material. Gold, for instance, is very suitable for transparent enamels and it may increase the color of the fondants used. Using opaque enamel on gold may be a waste and one should better use a copper alloy (tombak) for those purposes. The famous Alexis Falize did sin against this rule while creating the Japonaiserie jewelry in the 1860s.

Types of Enameling Techniques

Although the above provided you with a general layout of the steps involved in enameling, these change slightly with the different enameling techniques that evolved during the past millennia.

Marquetry Enamel

Marquetry enamel is a mixture of enameling, stone setting, and mosaic techniques.

During Roman times millefiori smalti were cut in shapes (as in mosaics) and placed in a metal border. The metal rims were used to set the glass secure after which the whole was fired in a furnace to create the fusion between metal and glass. Care was taken not to use too high of a temperature otherwise the colors in the smalti started to blend into each other, ruining the design.

Cloisonné Enamel

Cloisonné enamel (from French: cloison = “cell” or “partition”) is a technique in which flattened wires are placed in a pattern on a base metal sheet. These wires form compartments and they are either soldered on the plate or glued with a gum, such as tragacanth. This gum leaves no remnants after burning and thus will not stain the enamel or the base metal after firing in the kiln. When solder is used, great care should be given to remove any excess solder as this may stain the enamel – or worse, cause the enamel to peel off.

When the design is finished, the compartments are filled with prepared fondants of different colors. As different fondants require different kiln temperatures, one starts with the ones that need the highest firing temperatures. This to avoid the diffusion of colors from one compartment to the other (although not as necessary as in the enamel peinture technique). After firing the work is left to cool and the whole is finished with a carborundum file in a way that the metal rims are level with the enamel, followed by polishing (either by hand or by re-firing in the kiln). It is at this stage that it becomes apparent that the metal wires should be equal height throughout as some areas might need more filing than others. Uneven wire height would become immediately visible at this stage, something that one can not adjust. Additionally, when copper or silver wire is used, the enameling process can be followed by gilding of the exposed wires.

The earliest examples, to date, are from the Cypro-Mycenaean period (c. 1400-1000 BC) and were excavated during the 1950s in Cyprus. The 6 finger rings and the sceptre date back to the 13th and 11th century BC respectively. During the Byzantine period (ca. the 6th to 12th century AD) this art came to full blossom in the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as in different Celtic regions (Gaul and Britain) as can be seen from the Sutton Hoo finds at Suffolk, England.

During the 19th century, cloisonné enamel became popular again through the Japonaiserie (Japonism) jewelry by Falize and his master enameler Antoine Tard, who also worked for Christofle. Another famous enameler around the fin-de-siècle was André Fernand Thesmar, although he is most notable for his plique-à-jour enamels.

Champlevé Enamel

… this art was well practised in Florence, and I think too that in all those countries where they used it, and pre-eminently the French and the Flemings, and certainly those who practised it in the proper manner, got it originally from us Florentines. And because they knew how difficult the real way was, & that they would never be able to get to it, they set about devising another way that was less difficult. In this they made such progress, that they soon got according to popular opinion the name of good enamellers. It is certainly true that if a man only works at a thing long enough, all his practising makes his hand very sure in his art: & that was the way with the folk who lived beyond the Alps.1

Champlevé enamel (from French: champ = “field” and lever = “to raise”) is a technique that blossomed during the 12th century in the Rheno-Mosan area and Limoges (although already known to the Celts in the Early-Christian period). It is unknown if Cellini’s quote, above, was aimed at the 12th-century goldsmiths in the Rheno-Mosan and Limoges areas, but it is generally thought that these artists were influenced by the splendor of the Byzantine cloisonné enamels, knowledge brought back from the crusades.

The Rheno-Mosan area lies in the valleys of the Meuse and the Rhine rivers, roughly in the Cologne-Trier-Liège triangle, and comprised two schools with various workshops in this region. The first was the Rhineland school with its main ambassador Nicolas of Verdun and the Mosan school in the area that is now Belgium’s province Liège. The main artist of this region was Godefroid de Clair (or Godefroid de Huy). In these regions, as well as in the French Limoges area, there was asynchronous development of the champlevé technique, yet instead of gold, they used copper as the base of their designs. Although uncertain, we can assume that the technique of cloisonné enameling from Byzantine was mimicked with cheaper materials and this might well be what Cellini was referring to. His claim that it originated from Florence is probably more an expression of his chauvinism and self-indulgence that he is so famous for than based on fact.

The use of copper had the limitation that transparent enamel could not be used as is commonly applied on gold or silver. The reddish background would dull the colors too much and the obvious choice was opaque enamel. Nevertheless, they created beautiful pieces of art and both Nicolas of Verdun as Godefroid de Clair are recognized as the precursors of the Gothic era. In the late 15th century, the Limoges workshops stepped away from this technique and created the painted enamels for which they would be known worldwide (and still are).

Contrary to cloisonné enamel the depiction was not created through a series of wired designs, rather the figures and patterns are set in low relief on a slightly thicker plate. This is done through gravers, chisels or etching and resembles the glyptographic technique in which intaglios are made (only at a lower relief). Good care should be taken that the edges of the engraving (or etching) are sharp and straight and the design would not be as beautiful as intended on completion. After the compartments are filled with the colors of choice, and fired, the enamel is filed flat with a carborundum file and leveled with the surface of the metal plate. Gilding of the exposed metal provides for the final finish. A few other techniques (basse-taille, en resille and taille d’épargne) closely resemble this method of metal decoration.

Émail Brun

Émail brun (from French: “brown enamel”) was developed in the Rhineland area around the time they adopted the champlevé technique. Contrary to the name, it is not an enamel technique but rather a lacquering method like niello. A layer of linseed oil was applied to the surface of a copper base which turned a deep reddish brown on heating. Usually, the brown layer was then engraved and the engraving was to be gilded. The thicker the applied linseed layer, the darker the final color would be.

This is a surprisingly durable coating as can be seen from the enameled plaque on the tomb of Geoffrey de Plantagenêt in the cathedral of Le Mans, France which dates from the second half of the 12th century.

Peinture Sur Émail

Peinture sur émail (from French: “painted enamel”) is a type of painting with enamels. It was developed at the end of the 15th century in Limoges, France. In this technique, a slightly convex, metal plate is covered with a fondant of uniform color which was fired to produce a vitreous base for the drawing. On this, the artist starts applying color after color in thin layers onto the base color with a paintbrush. It is vital that one starts with the colors of the highest flowing temperature to avoid the diffusing of colors at a later stage. Between every step, the intermediate depiction needed to be fired in the oven to fixate the colors, sometimes up to 20 rounds of heating are needed for the final result. In this manner, one was able to rival the oil painters of the day and artists such as Leonard Limousin were in high regard, often even employed by the patrons of the arts. Needless to say that this type of enameling was no longer in the realm of goldsmiths, but belonged to those with exceptional drawing skills.

At the end of the 16th century the abundance of workshops that produced these artifacts – these could be a meter high – created a decline in craftsmanship which is usually associated with popular cultures. Like Castellani rescued the micromosaics from general decline by giving it a new impulse so did Jean Toutin from Blois, France give a new incentive to painted enamel in the early 17th century by introducing miniature paintings on enamel of high quality. These were now used in jewelry and as a decoration of watches and other objects de virtu. Typical for the Limoges painted enamels was the love for the horror vacui principle in which almost no part of the surface remained undecorated. One can see this still today on many of the Limoges painted porcelain items.

In Geneva, Switzerland, there was a culture of painting enamels from the late 15th century as well but the industry only really started to flourish mid-17th century. They specialized in portraits as in scenery images which soon attracted the attention of customers from all over Europe and beyond. Famous Genevan names of the day were Jean Petitot, Jean Etienne Liotard and various members of the Huaud family. Their products remained fashionable well into the 19th century until the application of photography, which they could not rival.2 Around the same period – ca. 1840 – the Genevan enamelers started producing jewelry in the neo-renaissance taste. These were however of a lower quality than their counterparts made abroad by masters as Giuliano.3

Grisaille Enamel

Grisaille enamel (from French: gris =”gray”) evolved in Limoges at the same time as painted enamel with the main difference being that grisaille enamels are created “ton-sur-ton”, with monochrome colors. The background was usually white and the sceneries were painted with black enamel of various tones to create contrasts through gray tones. It has been suggested that Jean Penicaud II first applied this technique on painted enamels, the technique was however already applied during the gothic era by painters (this painted grisaille equivalent would reach its, short-lived zenith around 1700).

Émail en Ronde Bosse

Émail en ronde bosse (from French: ronde = “round”; bosser = “to work”) was invented during the early Renaissance in the 15th century (although some finds indicate that it was used in the 3rd millennium BC on Crete). All other enameling techniques are done on flat, or slightly convex, surfaces while ronde bosse enamel is applied to 3-dimensional shapes. In pre-renaissance days this was impossible as the email would simply slide off the work, yet in the 15th century, they found that some gums – most probably tragacanth – could be heated without leaving a residue on the work. The latter was important due to the enamel not adhering to dirty or greasy surfaces. Prior to applying the first coating of enamel, the gum is applied to the metal background and carefully dusted with a feather to remove any air bubbles that might be present. The gum will now act as a glue for the enamel and will completely disappear after heating the enamel. Care must be taken to not fire the oven too hot or the enamel will get too fluid and drip off.

Other sources mention the original use of a plum pit gum (Prunus domestica domestica) as the gluing medium but this is uncertain. Cellini does not make any reference to the gum used, while he created beautiful artifacts with émail en ronde bosse. He does mention the use of a quince-pit abstract as an adhesive, mostly to restore old, unused, enamel fondant.

This technique was revived mid-19th century (as of c. 1840) to create neo-renaissance jewelry.

Émail de Basse-Taille

Émail de basse-taille (from French: basse = “low”; taille = “engraving”) is a technique very similar to email champlevé with a few differences. It was developed during the 13th and 14th centuries as a logical response to the fully explored champlevé technique.4

First, the metal is not engraved to create a lowered field of uniform depth, rather through the use of different gravers, the design was cut out in levels of various relief (from very shallow low relief to deep high relief). This enabled the scene to gain more depth than the traditional champlevé enamels. As this chiaroscuro effect could only work with transparent enamels, the choice of metal needed to be gold or – most often employed – silver. By applying the same enamel on various depths, a strong illusion of 3-dimensionality in the image could be achieved. The deeper areas would obtain a darker tone through the thickness of the enamel while the shallower areas were not only lighter in tone by the layer of the enamel, the reflecting surface of the silver enhanced this effect.

Unfortunately, not many of these items have survived from the late middle ages. The deeper areas caused the metal to be very thin at certain places, making it more susceptible to temperature changes. The enamel is susceptible to breaking off in those areas.

Émail de Plique-à-Jour

Émail de plique à jour (from French: “braid letting in daylight”) is, like émail en ronde boss, an invention of the Renaissance. It is similar to the cloisonné enameling technique, with the metal background removed to create a stained glass window effect. A framework of wires is soldered in the desired pattern – or a metal plate is sawn à jour to create a fretwork – and the partitions are filled with transparent or opalescent enamel. The pre-fired fondant would however soon fall through the openings if one doesn’t apply a base to it (as with cloisonné). For this purpose, the work is created on either a sheet of mica or a very thin plate of metal which would later be etched away in acid.

This technique became very popular at the dawn of the 20th century when master enamelers, such as André Fernand Thesmar, started to revive this technique. During the Art Nouveau period, it was the medium of choice for artists such as René Lalique, Philippe Wolfers, and others. These works still command high praise today.

One of the few examples that survived from the 15th century is the Merode Cup now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK.

Émail de Tailled d’Epargne

Émail de taille d’épargne (from French: taille = “engraving”; épargner = “to save”) is closely related to champlevé enamel with the distinction that with champlevé enamel most of the surface is decorated with enamel, while in the taille d’épargne method, it is the metal that makes up most of the surface. This technique is especially suited for lettering or fine accents.

Émail en Resille

Émail en resillé (from French: resiller = “hairnet”) is a very rare enameling technique that holds the middle between champlevé enamel and intaglio glyptography. The depiction was carved into a glass or crystal gemstone and lined with gold, to be enameled after. It was popular during a short time span in the early 17th century and not many items have survived.

The Kunstgewerbemuseum of the city of Cologne, Germany holds a beautiful golden crucifix with en resillé inlays.5

Enamel Photography

With respect to most other enameling techniques, enamel photography is a fairly recent (19th century) invention that probably comes closest to émail peinture than any other enameling technique.

Although the technique is not too complicated to perform, the underlying theory is too varied and too technical to fully describe. In one technique dichromates are added to colloidal substances (gums) which makes the latter photosensitive. An image is developed on a transparent sheet. After the first white, a fondant base is applied to a metal. This enamel is coated with a light-sensitive solution and covered with the transparent photograph, followed by light exposure. The exposed areas are now susceptible to moisture and black ceramic dust is carefully applied over the coating. The unexposed areas do not adhere to this dust and the surplus is removed. After firing the black ceramic is burned into the white enamel ground.

These techniques (there are many varieties) were applied first around 1850 and greatly suppressed the popularity of painted enamels due to their higher, and more lifelike, appearance.

Guilloché Enamel

Guilloché (presumably named after French engineer Guillot) is a symmetrical pattern engraving technique that is produced by a mechanical engine-turning table. The patterns that are created are plentiful and closely resemble those created by the “Spirograph” child’s play which was popular in the 1970s.

The rose-engine – as the machine is named – was used for plate engraving in the early 1800s, these plates however were never used to serve as a base for enameling. It was Carl Fabergé who first combined the technique of guilloché with enamel during the fin-de-siècle. It is therefore not a distinct enameling technique. Other jewelry houses such as Cartier soon followed Fabergè and this typical manner of decoration remained in fashion until WWI.

Pertabghar

Pertabghar refers to an enameling technique from India where a thick layer of green enamel was applied to a golden background and heated. While the enamel was still hot an open-worked golden plate was pressed into the molten mass. This technique was popular around 1870 (although it was also practiced in Ireland during the 6th to 8th century).

Repairs

The repair of enamels is a mission that one usually should not attempt unless one is specialized in this delicate task. Although the value of an artifact is affected by damaged enamel, restoration usually does not change this unless done with perfection.

Videos

Two educational videos by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London show how guilloché and champlevé enamel jewelry are made.

Sources

- De ontwikkelingsgescheidenis de emailkunst, Joanna Brom. Het Gildeboek: Tijdschrift voor kerkelijke kunst en oud-heidkunde 1937; 20: 102-122.

- Benvenuto Cellini, The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. Dover. ISBN 978-0486215686

- The painted enamels of Geneva, Switzerland, Fabienne Xaviere Sturm [1]

- Understanding Jewellery, Bennett & Mascetti, David & Daniela. Antique Collectors’ Club. ISBN 978-1851490752

- Schmuck II, Chadour/Joppien, Anna Beatriz/Rüdger. Stadt Köln.

- What does the expression “guilloché” mean?, Prof. J.C. Nicolet

- Fachkunde Edelmetallgewerbe. Rühle-Diebener-verlag

- Vaktheorie Edelsmeden. M.T.S. Vakschool Schoonhoven. 8e druk, 1985.

- Glass on Metal Various articles.

- Society of Dutch Enamellers Various articles.

- The Stavelot Triptych: Notes on a Mosan Work, Joyce Brodsky. Gesta, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1972), pp. 9-33. International Center of Medieval Art.

- The Enamel Plaque of Geoffroy Plantagenêt (Le Mans), François Velde.