© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Eyes have long been thought of as the window of the soul alternately revealing and concealing one’s deepest thoughts and feelings. Symbolically, the eye has turned up as the all-seeing eye of God long used by the Masonic Order, the French police adopted the watchful eye as a theme for buckles and belts and, during the French Revolution, the Revolutionary party used it to signify a member’s allegiance. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a more innocent interpretation of the eye as a simple love token appeared on the scene in the form of a miniature painting.

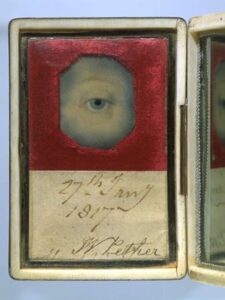

A “lover’s eye” miniature is a painted miniature of the giver’s eye, presented to a loved one. The notion accompanying this very short-lived fad (c.1790 through 1820) was that the eye would be recognizable only to the recipient and could, therefore, be worn publicly keeping the lover’s identity a secret. In contradiction, however, portraits from the period rarely show the sitter overtly wearing or holding an eye miniature thereby perhaps indicating that the wearers concealed these intimate portraits from view to further guard their secrecy.

Painted in watercolor on ivory or gouache on card, the miniatures were set in rings, pendants, brooches, and lockets for women and various containers such as snuff boxes and toothpick cases for men. A decorative border of burnished or engraved gold, gems or pearls usually surround the portrait and often a hair compartment was included on the reverse with a cipher or braided motif of the dear one’s hair. Eye portraits were always rendered in miniature, ranging in size from a few millimeters to a centimeter or two. The lack of any depiction of further details of the face surrounding the eye miniature serves to envelop the eye portrait with a great degree of anonymity. Gazing directly at the viewer, there is little doubt as to the focus of such a portrait, which, as you can imagine, could be quite intimate when the gaze is returned by the intended recipient of the painting.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

One popular theory as to the origin of the eye miniature purports that its roots stem from the late Eighteenth Century when the flamboyant, style-setting Prince of Wales was refused permission by his father, King George III, and by British law to wed the widowed (and Catholic) Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert. The widow avoided the Prince’s proposal by escaping to Europe. In order to keep his romance with her a secret from the disapproving court and in an effort to bolster his proposal, an eye miniature was conceived of and painted by Richard Cosway, a popular court miniaturist. Apparently, the gift of his gaze did the trick and they were secretly (and illegally) married. Cosway, in turn, painted the bride’s eye in order that she might covertly present it to the Prince. Soon, other British nobility followed the Prince’s lead and the trend spread to the continent, taking Europe by storm.

Another theory places eye miniatures as a product of France. According to Elle Shushan in the Essay The Artist’s Eye:

On October 27, 1785, Horace Walpole wrote to the countess of Ossory, “When human folly, or rather French folly can go so far, it would be trifling to instance a much fainter silliness; but you know Madam, that the fashion now, is it not, to have portraits but of an eye? They say ‘Lord don’t you know it?’ A Frenchman is come over to paint eyes here.1

There are further reports of eye miniatures painted by others as much as twelve years prior to the Prince of Wales’s ocular gesture of love. Study of the fee books meticulously kept by the prominent miniaturists of the period reveals entries on the books for eye paintings well before Cosway’s famous example. George Engleheart, miniaturist to King George III, (and rival of Cosway) records twenty-three eye portraits from 1775 to 1813 in his ledger.

Queen Victoria famously revived eye miniatures for use as presentation pieces. Sir William Charles Ross was the Royal Miniaturist to the Queen and therefore painted most of the eye portraits commissioned by her majesty. She ordered portraits of her children and many of her friends and other relatives. The art form was kept modestly alive through the early part of the twentieth century by a few devoted followers of the style, mostly members of the royal family or the aristocracy. Attempts were made by artists at the time to bring the fashion to America with little success.

In the early nineteenth century, eye miniatures had also evolved into a form of memorial jewelry sometimes referred to as ‘tear jewelry.’ The purpose of the eye portrait was refocused from secret love to remembrance. Decorated with a tear or depicted as gazing through clouds, the miniatures evoked powerful sentiment. Eye miniatures with a memorial intention usually also incorporated hairwork. The symbolism of the gemstones used to surround the portrait added to the sentiment. Pearls often represented tears when they surrounded an eye portrait. Diamond, a motif employed only by patrons with the means to pay for them, represented strength and longevity. Coral is said to protect the wearer from harm, or perhaps to protect the subject of the miniature from harm? Garnets were very popular in Georgian jewelry and are said to have represented true friendship. Turquoise‘s association with ocular health was an interesting choice both as a surround for an eye miniature and a talisman for the wearer.

These very personal love tokens are very rare and highly prized.

Sources

- Boettcher, Graham C. (editor). the Look of Love: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection: D. Giles Ltd.: London, Birmingham Museum of Art, 2012.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington Dawes with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714-1830: Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Grootenboer, Hanneke. Treasuring the Gaze: Intimate Vision in Late Eighteenth-Century Eye Miniatures: Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Victoria and Albert Museum.

Notes

- The Look of Love p. 18.↵