Introduction

Halfway through the 15th century general art styles changed in Italy. Artists started to draw inspiration from the Ancient Greek and Roman world. Funded by the royal families from extremely wealthy Italian cities many artists were able to devote their lives to their personal development of skill and style. The classical influence was not as much a copying of techniques, but more a general style that was derived from ancient sculptures.

Jewelry wasn’t influenced directly; hardly any ancient jewelry was known in those days apart from the surviving cameos which had remained fashionable objects throughout the Middle Ages. Ancient techniques like filigree or delicate, all gold jewelry weren’t revived but rather, it was the classical and mythological themes that provided the link with the ancient world. The Biblical themes from the Middle Ages never lost their popularity throughout the Renaissance and continued to provide depictions for jewelry. From Italy the style spread north gradually over the 16th century, slowly replacing the Gothic style of the Middle Ages.

Styles & Techniques

A new art style was obvious in painting and sculpture and it is through these two art forms that jewelry was influenced most. Many great artists of the Renaissance started off their careers in goldsmith workshops to learn about accuracy of line and clarity of style.1 This caused a close relationship between painters/sculptors and goldsmiths and probably explains the excellent depiction of jewelry in Renaissance portraits. These paintings allow us to form an unprecedented insight into the jewelry that was produced during this period besides the study of the few surviving pieces.

The European nobility found itself in need of vast sums of money to fund their numerous wars and jewelry was considered as portable wealth. The numerous descriptions of pawned items provide another good source for the jewelry history researcher who tries to get a good idea of the jewelry of the time.

Surviving pieces show extraordinary craftsmanship but, as mentioned, it is from paintings and designs that we start to realize the full splendor of Renaissance jewelry. Goldsmiths became masters of certain techniques within their trade and specialism became a virtue. It wouldn’t have been uncommon for a jewelry item to be designed by a painter, cast and shaped by one goldsmith, engraved and enameled by another and then set with gemstones by yet another specialist. Apart from difficulties attributing a jewelry item to one workshop it even is hard to divide Renaissance jewelry into well-defined groups according to production areas. Goldsmiths were employed from abroad and the international availability of printed jewelry designs caused a blend of jewelry styles to occur all over Europe.

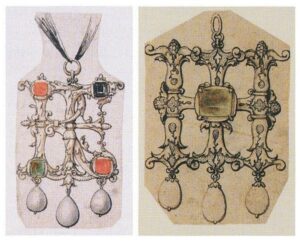

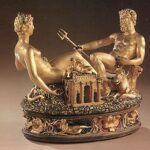

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

The change in jewelry design gradually spread from Italy to France and then to Germany and England following the new style of painting and sculpting over the first half of the 16th century. Miniature sculpture in jewelry is a very evident consequence of the influence of the greater arts on jewelry design. Another important aspect of the change and spread of jewelry styles was the fact that painters started to produce engraved designs for jewelry that could be printed and consequently spread in large numbers over the whole of Europe. Many of these designs have survived the last 500 years and show close relations to the Mannerist art style.

When the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian I married Bianca Maria Sforza from Milan in 1494 his court opened up to the Italian arts. The spread of the Renaissance through the Holy Roman Empire was a slow and gradual event and Gothic jewelry continued to be popular until deep in the 16th century. That said, the German masters adopted the Renaissance style halfway through the century and their cities became important production centers that attracted goldsmiths and designers from all over Europe. Augsburg eventually became one of the premier jewelry manufacturing cities.

Thanks to Benvenuto Cellini‘s ‘The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture’ we have a comprehensive understanding of the techniques used by Renaissance goldsmiths. Cellini has done an excellent job describing in detail the methods available to the goldsmith of the time. Reading his treatise is highly recommended for those who wish to understand goldsmithing in the 16th century. It covers the art of niello, filigree work, enameling, stone setting, foiling, diamond cutting, casting, gilding and many other aspects of the goldsmith’s trade.

A new enamel technique was invented by the beginning of the 17th century: that of émail en résille. During this time a few new decorative styles emerged as well. Designs became more naturalistic and patterns by the arrangement of gemstones started to dominate. The Renaissance started to give way to the Baroque.

Materials

The influx of gemstones into Europe was greater than ever in the 16th century. Vasco Da Gama had found a direct sea route to India on his adventure around the Cape of Good Hope over the years 1497-1499. This route allowed European merchants to start obtaining gems in India directly, an event that caused the influx of diamonds to increase immensely. Lisbon replaced Venice as the main trading center for Indian gems. Bruges had been the main diamond-cutting center in the 15th century but by 1500 the sea arm leading to its port silted and the diamond-cutting industry moved house to Antwerp. The industry prospered there until 1585 when the city became entangled in the 80 Years War between the Spanish sovereign Philip II and the revolting Dutch city-states. The Spanish occupied Antwerp in that year and the Dutch navy blocked the sea access to the city, crippling Antwerp’s international trade. A large number of diamond cutters moved further north to Amsterdam which became, and remained, the diamond-cutting center of Europe until the 20th century. We should not forget to mention Paris, where a community of diamond cutters was active as well. The most common diamond cut was the table cut until, in the early 17th century, the rose cut became popular. The Renaissance also saw the return of the art of cameo cutting.

Colored stones remained very popular as well with sapphire, ruby and emerald being the most sought-after stones. Apart from Lisbon, Barcelona became an important trading center of colored stones following the plundering of South America by the Spanish and Portuguese. At first burial sites and temples were the main source of precious stones, silver, and gold but by the mid-16th century the Spanish had located the Emerald deposits in Colombia and established mines. The Portuguese further occupied Sri Lanka, establishing direct access to the corundum deposits on the island. Burmese rubies were highly prized because of their supreme color. Pearls were extremely popular and were mainly obtained from the Persian Gulf.

Imitation gem production flourished. Glass stones, foiling and the production of doublets were common practices. Imitation diamonds made of glass, rock crystal or colorless zircon from Sri Lanka entered the market as well. In Venice, the production of imitation pearls became enough of an issue that the legislators of the city put severe sentences on the practice: 10 years of exile and the loss of the right hand.

Types of Jewelry

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

The most important jewelry item from the Renaissance was the pendant. It replaced the Medieval brooch as being the most common jewel and was worn on a necklace, long gold chain, fixed to the dress or on a chain worn on the girdle. The pendants were often designed to be seen from both sides with their enameled backs equally impressive as their jewel-encrusted fronts. From the late 15th century, functional pendants like tooth and ear-pick pendants are encountered as well.

Devotional pendants remained in fashion depicting Biblical scenes in miniature sculptures or the sacred monogram with the letters IHS, believed to have come from the Greek word for ‘Christ’. Pendants featuring the bejeweled initials of the wearer and his or her partner or other loved one are often encountered in designs as well but few have survived to the present day. These jewels were so personal that they were often destroyed after their wearer died.

Pendants featuring portraits painted in enamel, as well as depicted by cameos were very popular, as were Arabesque motifs, fruit, foliage, scrolls and putti. Mythological subjects like nymphs, satyrs and fantasy beasts like dragons became popular next to the already popular Biblical depictions. The stories from sea-faring adventurers triggered a fashion for jewelry with ships, mermaids, and sea monsters.

Rings continued to be worn on all five fingers and even on more than one joint in Medieval fashion. They usually were gem set and were ornamented more profusely than ever before. Hidden spaces under the bezel of the rings allowed scented materials to be hidden in an attempt to cover up the bad odors that were the result of bad hygiene. The hand wearing the ring could be brought up to the nose whenever a smell became too much to bear. Rings have been encountered with compasses and sundials in them and later in the 16th century, actual clocks were incorporated in them.

The first portable timepiece had been developed somewhere around 1500 but watches as such didn’t exist yet. The timepieces were incorporated into existing jewelry such as rings, pomanders, and pendants. The pomander was another jewelry item that was used to obscure bad hygiene, loaded with a scented gum or perfume. The situation was so bad that people used flea furs, the skin of a fret or mink, hoping that any fleas would prefer the furry skin over their own body. In this time of splendour even these flea furs were subject to ornamentation as can be seen in the right hand of the Lady portrayed on the right. The painting has been attributed to an English painter and is dated around 1595.

Dress jewels started to appear all over the bodice of dresses rather than just on the edges as had been the fashion in the Middle Ages. Aiguillettes, clasps, gold trinkets and clusters of stones or pearls were attached all over the dresses of the European nobility. As a matter of fact, just about everything that could be jeweled was submitted to gemstone and gold encrusting.

Earrings made their comeback after disappearing for a while over the Middle Ages. They were often simple pear-shaped pearls or jewelled drops that were either suspended from a pierced ear or tied around the ear. Single jeweled letters, blackamoors or (fantasy) sea creature earrings have been encountered as well. From the early 17th century we see a more geometric design and the length of the earrings increased. A new sight on the heads of the later Renaissance ladies were aigrettes.

A Look into Renaissance Fashion

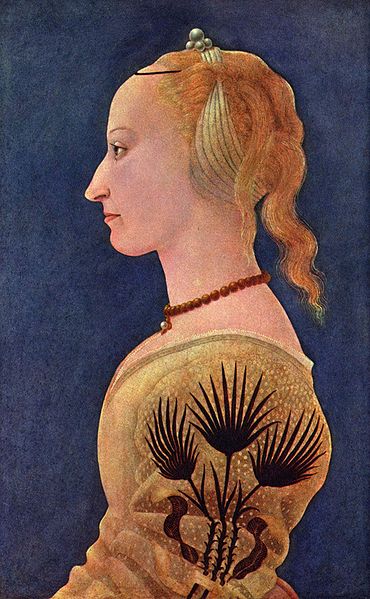

Early Renaissance Through Paintings

From the second half of the 15th century onward the bulky head-dresses of the Middle Ages gave way to carefully fashioned hair decorated with strings of pearls and ferronieres. New dress fashions with receding necklines caused the return of the necklace, which had disappeared from female necks over the Middle Ages. In the portraits depicted above and below this text, these changes are nicely illustrated. Necklines receded further as time progressed and the head ornaments became more delicate.

High Renaissance Through Paintings

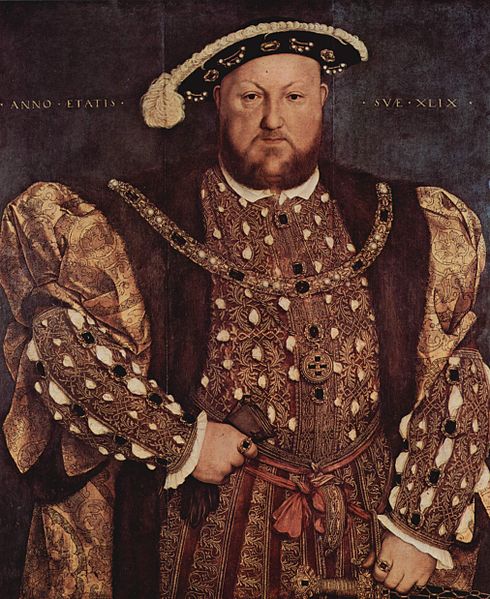

The English Court Under Henry VIII

This portrait of the infamous British King illustrates the types of jewelry that were very typical for the first half of the 16th century. Let’s start with the hat jewels that Henry is wearing. The soft velvet hats were in fashion throughout Europe and were often decorated with one or more badges that ranged from simple buttons to complex jewels. The most typical hat jewelry was a gold, circular medallion depicting Biblical or mythological scenes. Cameos were very popular as well.

From the hat down we encounter a heavy gold collar set with pearls and diamonds from which a chain is suspended holding a round pendant set with precious stones forming a cross. The chain compliments his bejeweled clothing. Matched sets of jewels and clothing forming parures were much loved in the Renaissance and records of just about every sovereign owning a few of these parures have been found.

On both his index fingers he wears a ring, set with a faceted stone.

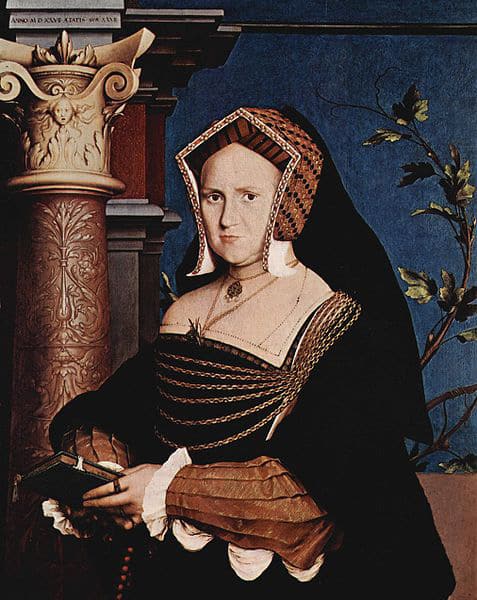

These three portraits (Mary Wotton, Lady Guildenford on the left, her husband, Sir Henry Guildenford in the middle and Jane Seymour, Henry VIII’s third wife on the right) provide an insight into the fashion among English nobles at the end of the 1520’s. The ladies still wear a bulky Medieval head dress but their dresses are up to date with a low square neckline. Lady Guildenford wears a short necklace with a pendant, rings and has long gold chains running along the bodice of her dress in the same fashion as her necklace. Lady Seymour is wearing a parure that matches her dress. Sir Guildenford has an emblem as his hat jewel and wears a heavy collar featuring a pendant.

Anne of Cleves was Henry VIII’s fourth wife. The portrait shows her wearing an elegant parure. Her head is covered in a coif which has an unusual pendant fixed to its left side, hanging over her left ear. The rims of her coif are jeweled in the northern fashion. Her short necklace is formed of gem-centered flowers with white enamel, matching the border on her dress. A gem-set cross pendant is suspended from it. She further wears a long chain of heavy links spanning her neck twice. Several rings adorn her hands.

Around the middle of the 16th century, the square low-cut dresses gave way to a new fashion of high-collared ones. An intermediate example can be seen here with Elizabeth Seymour displaying a simpler, but by no means less elegant dress with an affixed gold pendant, a necklace, and several rings.

The era of Elizabeth’s reign (1558-1603) saw a different fashion. Men had been wearing just as much, or perhaps, even more, jewelry than women under Henry VIII, but this now changed. Elizabeth was very fond of jewelry and it shows in the many portraits that were produced of her. Following her example, women started to wear more elaborate jewelry than men. Dresses were closed at the neck with high collars and necklaces worn over the dress, suspending large pendants. Twenty-seven-year-old Elizabeth is wearing a rather modest outfit with a few aiguillettes as the only dress jewels.

Here, some 15 years later she is wearing a far more elaborate dress. Her hair is adorned with pearl strings and other jewels. Around her neck are a pair of very long pearl strands that cascade across the excessively jeweled bodice. A large pendant with a huge ruby is suspended from her girdle. The sleeves of the dress exhibit pearls near the wrist and the shoulders. Look closely, there is a bejeweled crown on the table behind her left elbow.

In this portrait, it is obvious how fond Elizabeth was of jewelry. Her dress is encrusted with pearls and jewels. She’s wearing a headpiece of gems and pearls. Jeweled agraffes march down the front of the garment. A large chain of office with pearls and gems drapes from her shoulders and the shoulder edges bear gems as well. Behind rests a triple-stranded pearl necklace. It also appears that the white slashes in the portrait probably represent aiguillettes. A bejeweled ermine rests on her left wrist. Her collar is dusted liberally with pearls and she is wearing a jeweled ring.

Philip II of Spain illustrates the sober way of fashion that was common among the men of Spain. A sedate line of aiguillettes is arrayed along the brim of his hat. He’s wearing a chain of office suspending a golden fleece pendant and he has jeweled buttons on his jacket and cloak. The strap and hilt of his sword appear to be adorned with gold.

His daughter, Catalina Micaela wears a more elaborate parure of necklace and belt along with strings of pearls, and rings. There are pearls in her hair and on her hat, gem-set ouches or aiguillettes are arrayed down the front of her garment. Around 1600 laws were put in place by Philip III, the successor of Philip II which restricted jewelry for women and prohibited the manufacture of jewelry with relief for all purposes other than church plate.

France

A portrait of Francis I (reign: 1515 until 1547,) a contemporary of Henry VIII and dressed in a very similar way with a velvet hat featuring hat jewelry in the form of an enseigne and aiguillettes and a bejeweled tunic. Francis loved jewelry and actually started the concept of ‘Crown Jewels’ in 1530 when he declared that certain pieces would be inalienable heirlooms to his successors. The concept of an heirloom only concerned gemstones so resetting was still possible and jewelry was often updated. Other monarchs followed his example in the years after his reign. Ironically, Francis found himself having to pawn off most of his jewelry and by the end of his life, the majority of his collection was tied up elsewhere as collateral.

Son of Francis I, Henry II is a sovereign said to have disliked jewelry. During his reign, France got entangled in a long period of war and disruption and consequently, jewelry took a fall. Perhaps ironically, we find him here depicted in painted enamel on gilded copper.

Elizabeth of Austria, Queen of France between 1570 – 1574. This portrait was painted circa 1571 and depicts her wearing a jeweled dress set with rubies, diamonds, and pearls.

Related Reading

Timeline

Renaissance

Discoveries & Innovations

- Benvenuto Cellini is Born in Italy, describes Plique à Jour Process in ‘Treatises’ in 1568.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Probierbüchlein (Little Book of Assays) Published, Becomes an Important Guide to Assaying of Metals.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Spanish Conquistadores Send Colombian Emeralds Back to Spain.

Jewelry History

- Arabesque Style Becomes Popular in Renaissance Scroll Work.

Discoveries & Innovations

- First European Lab for Smelting Ores to Test for Gold.

- Silver Found in the New World on Roanoke Island, VA; Settlement Evacuated 1586.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Colorless Zircons Mined in France.

General History

- The Baroque Period Starts.

Jewelry History

- Human Hair First Worn in Memorial Jewels.

Sources

- Benvenuto Cellini, The Treatises of Benvenuto Cellini on Goldsmithing and Sculpture. Dover.

- 7000 Years of Jewellery, Various Authors, edited by Hugh Tait, British Museum Press, London, 1986.

- Jewelry, from Antiquity to the Present, Phillips, Clare, Thames & Hudson, London, 1996.

- A History of Jewellery 1100-1870, Evans, Joan, Dover Publications, Inc, New York, USA, 1953/1970.

- A History of the Modern World, 8th edition, Palmer, Robert. R. & Colton, Joel. McGraw-Hill, Inc. New York, USA, 1995.

External Link

- Kleinodienbuch der Herzogin Anna von Bayern – BSB Cod.icon. 429, München, 1552 – 1555 in the digital collection of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. A digitalized book full of illustrations giving you a great view into 16th-century jewelry!

Notes

- A History of Jewelry 1100-1870, Joan Evans.↵