Introduction

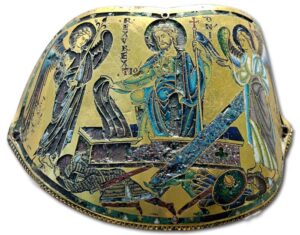

Essen’s Cathedral Treasury. c. 1100.

The style which followed the influence of Byzantine architecture and arts on the rest of Europe is called the Romanesque style. It became widespread in Northern Europe when Charlemagne (Charles the Great) was crowned emperor in 800. This event made him the equal of the Byzantine ruler, a situation which called for a court style with equal ‘grandeur’. The Christian character of Byzantine jewelry together with its techniques was adopted by the Carolingian and later the Ottonian courts. Strong ties between the two courts and the Byzantine one were established by marriage and diplomacy over the centuries.

The Byzantine styles remained in fashion for over four centuries until, in 1204, the fourth crusade came no further than the plundering of Constantinople. Although this event brought back new ideas and vast amounts of precious stones and metal to northern Europe, the position of the Byzantine Empire had been compromised. Its powers dwindled and its style gradually fell from favour in the decades after the plundering of the capital. In the early 15th century, the Romanesque style gave way to the new Gothic style. Typical Romanesque items like earrings and bracelets disappeared in Northern Europe for several centuries.

Romanesque jewelry was for the most part dedicated to the church. Personal jewelry, although present, was of lesser importance during the younger days of the Romanesque period. During the period 600 – 1000 AD most of Europe had converted to Christendom, a process in which monasteries played a key role. These monasteries were founded throughout Europe and the monks living there occupied themselves with the production of jewelry. One example is the 9th-century Isenric of St Gall who established a tradition of fine goldwork in his monastery. In the 10th century, monk goldsmiths were recorded all over Europe. But it wasn’t just the production of gold work that we can attribute to these monks, their workshops acted as schools for secular apprentices as well thus spreading their skills and knowledge.

The transfer of know-how from ecclesiastic to secular goldsmiths enabled new craftsmen to set up shop in the new cities which rose during this time. By 1180 the goldsmiths of London started to work together in a guild and in 1200 the goldsmiths of Paris were described:

…sit in their shops at their little counters in front of their furnaces making cups of gold and silver, brooches, jeweled bracelets and clasps and setting jewels in rings”.1

There seems to have been no differentiation between the profession of the jeweller and the goldsmith; they were one and the same person. An increase in jewelry wearing must have taken place by the end of the Romanesque period, something we can derive from new laws that were put in place restricting jewelry available to commoners. (Sumptuary Laws)

Materials

Gold remained the most prestigious metal used for jewelry. Precious stones were very important and entered Western Europe through the Italian traders in Venice and Genoa who obtained them in Constantinople. The crusades (starting in 1096) first brought vast amounts of new materials into Europe. In the 12th and 13th centuries, there was a stagnation of trade with the East as a result of hostile relations between the Christian West and Muslim East. In addition, the Spanish Crusade caused a break in trade with Arab Spain.

Precious stones weren’t popular because of their beauty alone. The 11th-century bishop and writer Marbod documents the beliefs of the powers of precious stones in his Libellus de lapidibus, a work about which is said to be:

…the classic on the subject of the marvelous properties of stones.2

Different stones shielded the wearer from all kinds of harm and sickness. These beliefs had come straight from the ancient past and still live on today.

Styles & Techniques

(c.1170-80).

The styles and techniques used in the Romanesque period are similar to those of the Byzantine Empire. Christian motifs were the most popular and dense surface decoration was a remnant of Germanic times. Most of the innovation that took place occurred at the end of the period and may be better attributed to the newer Gothic period.

It may be interesting to note that a fair amount of precious stones in Romanesque jewelry seem to be recycled stones from Byzantine jewelry. Many stones set in collets on royal jewelry show drill holes, indicating that they had a different purpose at an earlier date.

Types of Jewelry

Personal jewelry in the Romanesque period was often functional but sometimes purely decorative jewelry. Belts, brooches, and signet rings are the best examples of functional items that were turned into jewelry. Brooches were either used as garment fasteners or were sewn onto dresses in the Byzantine style. Precious stones and pearls were used to enhance fine fabrics in patterns or as loose stones attached to robes’ rims and seams. One of the most important items at that time was the belt. Naturally, these belts became subject to decoration. Their buckles could be of precious metal and the leather was a perfect place for precious metal clasps, sometimes adorned with gemstones. After the Byzantine examples, purely decorative jewelry like pendants, earrings, chains, necklaces, bracelets and gem set rings were also worn. The crown was an important item as well, again after the Byzantine example.

The heavy draperies of these times left little room for jewelry. The quality of the fabric and embroidery, together with jewelled brooches sewn onto the dress were a prevalent way of expressing status. Cameos, especially Roman and Byzantine ones were highly fashionable and played an unusually large part in jewelry.

We can’t discuss Romanesque jewelry without mentioning the magnificent jewel-encrusted reliquaries, book covers and other objects that do not really fall under the term ‘jewelry’ when ‘personal decoration’ is used to define the term. Reliquaries in particular often form a great remnant of style and a great indicator of techniques available to the goldsmith of that day. Where personal jewelry often got lost over time these reliquaries have survived to the present because of their spiritual significance and the fact that they were in the possession of the Church.

The Treasures in 'Der Schatzkammer' in Aachen, Germany

Sources

- Middeleeuwen, de Boer, D.E.H, van Herwaarden, J and Scheurkogel, J. Martinus Nijhoff uitgevers, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1995.

- 7000 Years of Jewellery, Various Authors, edited by Hugh Tait, British Museum Press, London, 1986.

- Jewelry, from Antiquity to the Present, Phillips, Clare, Thames & Hudson, London, 1996.

- A History of Jewellery 1100-1870, Evans, Joan, Dover Publications, Inc, New York, USA, 1953/1970.