Popular throughout the Victorian Era, the jewelry we think of as “Scottish” is just as likely to have been made in England as in Scotland. Also referred to as “pebble” jewelry, this colorful and exuberant jewelry originated in Scotland utilizing traditional Highland themes employing native agate and granite to punctuate the popular designs. Much of Scotland’s Highland heritage was squelched after the 745 rebellion against the English and outward symbols of clan allegiance were forbidden. At the turn of the nineteenth century interest in Scotland was renewed in the readers of the popular historical novels, penned under a cloak of secrecy, by Sir Walter Scott. Basing his stories on the rich history of the Highlands, he presented an idealized and romanticized view of his beloved Scotland, drawing interest from all corners of the globe. In 1822 Scott planned and executed a spectacularly ceremonial visit to Scotland by King George IV, the first by a Hanoverian monarch. The King paid homage to Scotland’s proud Highland traditions by appearing in a Royal Stuart tartan kilt and plaid and unwittingly began a long tradition of Royal visits. Queen Victoria made her first visit there in 1842 and loved it so much that she purchased Balmoral Castle in 1847, making it a home for English monarchs into the twenty-first century.

Railways were popping up all over the British Isles and connecting people and places like never before. A new “tourist” trade sprang up as folks who were previously not able to afford leisure travel now found not only the means but the mode. Scotland became a prime destination not only for its beautiful scenery but also because of the fascination it held for its Queen.

Wearing the Royal Stuart tartan became a regular sight for anyone keeping an eye on the monarchy. Prince Philip adopted it and the Princes Albert and Alfred had their portraits painted wearing their kilts. The opening ball for the 1851 Great Exhibition was another occasion for the children to exhibit their tartans and, in 1855, the Prince of Wales wore Highland dress for the Fete at Versailles. At times it seemed like the Queen was single-handedly keeping the tartan manufacturers in business through her distribution of Highland-style gifts to family, friends and Royal retainers.

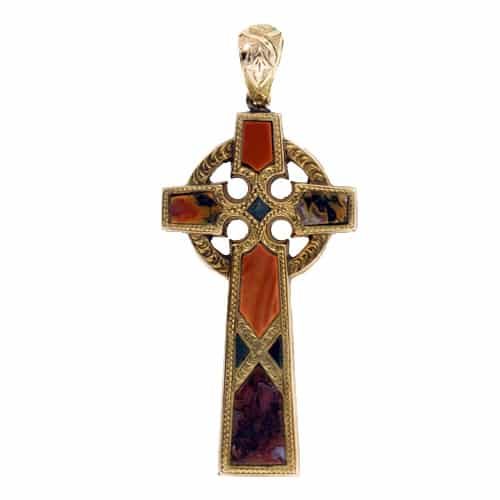

Along with the tartan came the traditional functional jewelry used to secure plaid wraps and kilts. Most of the jewelry was in silver rendered by local silversmiths, often with intricately hand-engraved designs that included meandering Celtic knot motifs, flowers, leaves and other natural themes. Native “pebbles” of Scotland, notably agates, amethyst, rock crystal, granite and cairngorm along with local river pearls and colorful enamels, were used to create multi-hued accents and patterns in the traditional motifs. The stones were precisely cut to form designs conforming to the setting, often to such tight tolerances as to form a seemingly seamless mosaic.

Annular and penannular brooches were the traditional styles used to hold the plaid at the left shoulder and were the first to be swept up by the growing tourist trade. Endless Celtic knots, shields and crests, clan symbols (usually featuring a “sprig” of a local plant) and the “Cross of St. Andrew” (Scotland’s patron saint) were other traditional designs used for this purpose. Kilts were secured by dirks, small replica knives with jeweled hilts and scabbards, some of which were even functional.

Having the longest Highland tradition, heart-shaped brooches, usually surmounted by a crown, thistle, or fleur-de-lis, were known as “Luckenbooth” hearts, taking their name from the small lockable booths in St. Giles’s Kirk in Edinburgh where they were first sold. When these featured two intertwining hearts, the letter “M” was formed at their intersection and they were known as “Queen Mary” brooches. Thought to ward off evil spirits, these were widely distributed as love tokens.

Inevitably, there was enough demand for “Scottish” souvenir jewelry that the local jewelers had trouble keeping up. By the mid-1800s, business opportunities were recognized by jewelers in other parts of Great Britain and they were soon making “Scottish” jewelry in Birmingham and Exeter. Birmingham’s booming jewelry manufacturing industry, including die-casting, was particularly well suited to the creation of this type of jewelry. Along with the export of it’s manufacture, the motifs used in the design of “Scottish” jewelry began to follow the demands of English fashion if not strictly Highland tradition.

At first non-traditional designs crept in that still “gave a nod” to Highland themes like bagpipes, rowboats, knights, and tam-O’shanters. Eventually, there were heart and shield-shaped padlock closures and “Order of the Garter” designs, including strap and buckle motifs, followed by anchors, arrows, horseshoes, serpents (Queen Victoria’s favorite), stars and seashells. No longer just kilt and plaid fasteners, there were bracelets, earrings, pendants, boxes, cuff links, almost every type of jewelry and accessory sported by the fashionable English man or woman. Brooches could be seen adorning hats, blouses, cloaks, capes, and cravats, they were not just for securing tartans anymore.

With the outsourcing to Birmingham, the use of “pebbles” from Scotland dwindled. Birmingham jewelers used stones from other sources and had them cut in the world-famous cutting center in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. The fittings were manufactured in England and then sent to Germany to have the stones expertly cut, fitted and set. Circa 1870, there was even a penchant for malachite set “Scottish” jewelry and this distinctive banded green stone had to be imported from Siberia for the purpose. Later styles, circa 1880-1900, included plain mounts that served to secure the stones with very little, if any, silver showing in between.

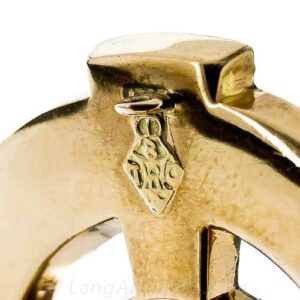

Much of the pebble jewelry produced was unsigned. A diamond-shaped Design Registration Mark (1842-1883), known as a “kitemark” does appear on some jewelry. Kitemarks from 1842-1867 consisted of the “Class” at the top within a circle, the “Year” at the top, the “Month” at the left point, the “Day” at the right and the “Bundle” number at the bottom. From 1868-1883 the “Day” was at the top, “Bundle on the left, “Year” on the right and “Month” at the bottom. These marks are helpful in dating a piece but do little, if anything, to identify the maker. Jewelry made in Birmingham is sometimes marked with the full complement of marks including the anchor, lion passant, date letter, maker’s mark and duty mark.

Historians have used the catalogs from the International Exhibitions to identify who the major players were in the Scottish jewelry trade. Aberdeen jewelry was generally of minimalist design with little if any, engraving and featured salmon pink and gray granite. The best-known Aberdeen jewelers were M. Rettie and Sons and Jamison. Birmingham jewelers Bradford and George Unite along with Exeter jeweler, Ellis and Sons were known to produce cape pins and “safety-chain” brooches. Edinburgh goldsmiths, G&M Chrichton excelled at plaid brooches in silver decorated with citrine and amethyst. Other notable Edinburgh jewelers include McKay and Cunningham, Marshall and Sons and Meyer and Mortimer. Also included in the company of these more well-known Scottish jewelers would be James Muirhead and Sons, Glasgow, Royal Jewellers.

The passion for this remarkable jewelry remained high throughout the Victorian era. The fact that the style was both fashionable and affordable had more than a little to do with its popularity. The colorful mosaics and whimsical designs seemed to stay new and fresh well into the start of the twentieth century. Following World War I, its popularity waned a bit, but a large quantity of pebble jewelry was still being made. “Scottish” jewelry produced in the post-World War II era is not as fine and the quality of the agates doesn’t come close to those in the jewelry produced during the reign of Queen Victoria.

Sources

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Reddington Dawes, Ginny, Davidov, Corinne. Victorian Jewelry: Unexplored Treasures. London: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1991.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Scottish Jewellery: A Victorian Passion. Milan, Italy: 5 Continents Editions, 2009.