Egyptomania is an extreme obsession for all things Egyptian and, throughout history, a passion for Egypt has been a recurring theme. By the time Napoléon Bonaparte stormed Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, Egyptomania had already reached the level of obsession in France and his actions thrust it even further, onto the world stage. Not strictly a military campaign, scientists and scholars accompanied the army and noted their observations for all the world to share. While Bonaparte was eventually defeated, this campaign led to the 1799 discovery of the Rosetta Stone, which was essential in the creation of the field of Egyptology.

The scientific/scholarly side of the endeavor resulted in the publication of many books detailing observations and knowledge gained during the campaign. Vivant Denon’s book, Voyage en Haute et Basse Egypte (1802) was a creative spark for artists, designers, and, indeed, all aesthetic ventures. Egyptian décor began to appear in all facets of the decorative arts in France, propelled in part by Emperor Napoléon’s command. In 1833 an obelisk from the Luxor Temple, gifted to the French by Pasha Muhammed Ali, arrived in Paris. The monolith was erected in the Place de la Concorde to great fanfare where it became a beacon of inspiration to all. Jewelers were not immune to these stirring discoveries and soon jewels bearing an Egyptian theme began to pop up in store windows along the tony streets of Paris.

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, this new field of Egyptology spawned numerous archaeological expeditions to the region with the anticipation of treasure among the tombs of the Pharaohs. From 1859-1869, the Suez Canal was under construction and the French fascination for the project was so pervasive that the Paris Exposition of 1867 featured Egyptian-inspired jewels from Boucheron, Mellerio, Baugrand, and others. Empress Eugénie herself (wife of Napoléon III) requested jewels in the Egyptian taste from her court jeweler, Lemonnier (most famously an aigrette with a lotus flower and bird’s wings). The thirst for Egyptian-themed jewels soon spread across the continent and jewelers such as Giuliano, Castellani, and Fontenay included some Egyptian revival jewels alongside their other archaeological and revival styles.

While they took their inspiration from these Egyptian themes, the designs that resulted were not authentic to the Egyptian style, just thematically derivative of the motifs. Cloisonné enamel, which was a Second Empire favorite, was often used to depict Egyptian designs, which while popular, was not historically accurate. In fact, “revival” might not be the proper terminology when compared to other movements, such as the Etruscan revival, which had jewelers like Castellani striving for exact duplications in technique and style. At the fin-de-siècle, when the fashionable jewelry mode was Art Nouveau, Egyptian motifs remained prevalent.

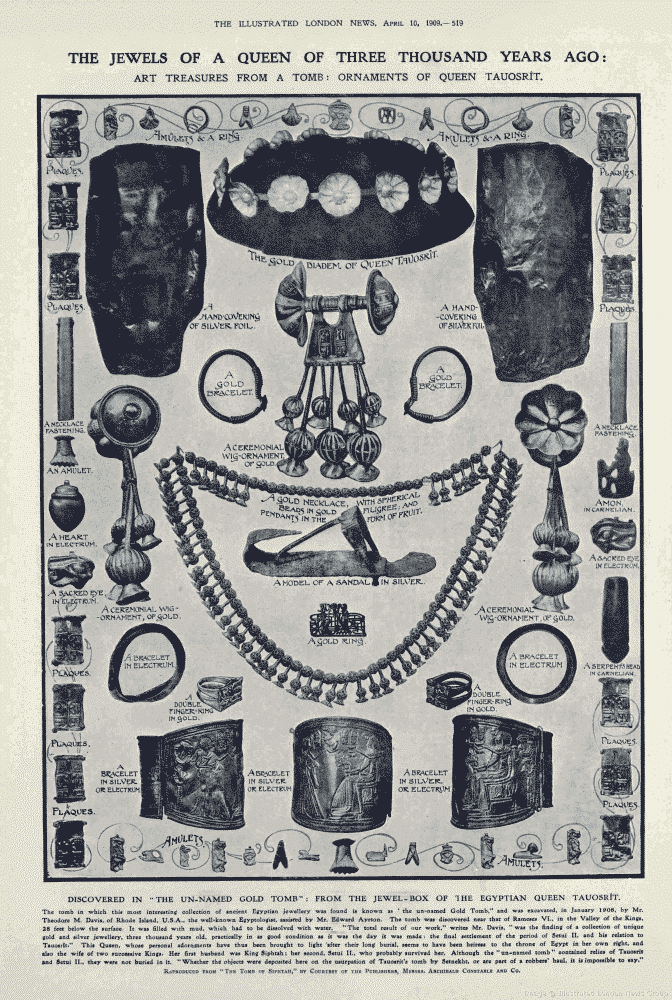

Continued exploration of the region and amazing discoveries kept Egyptomania in full swing throughout the early part of the twentieth century. Gaston Maspero opened the temples at Karnak, Edward Ayrton found a royal tomb at Thebes in 1908, and Borchardt found the bust of Nefertiti c.1912, to name a few. Spurred on by treasure dealers who came to Paris to ply their wares, antiquities were finding their way into collections around the world.

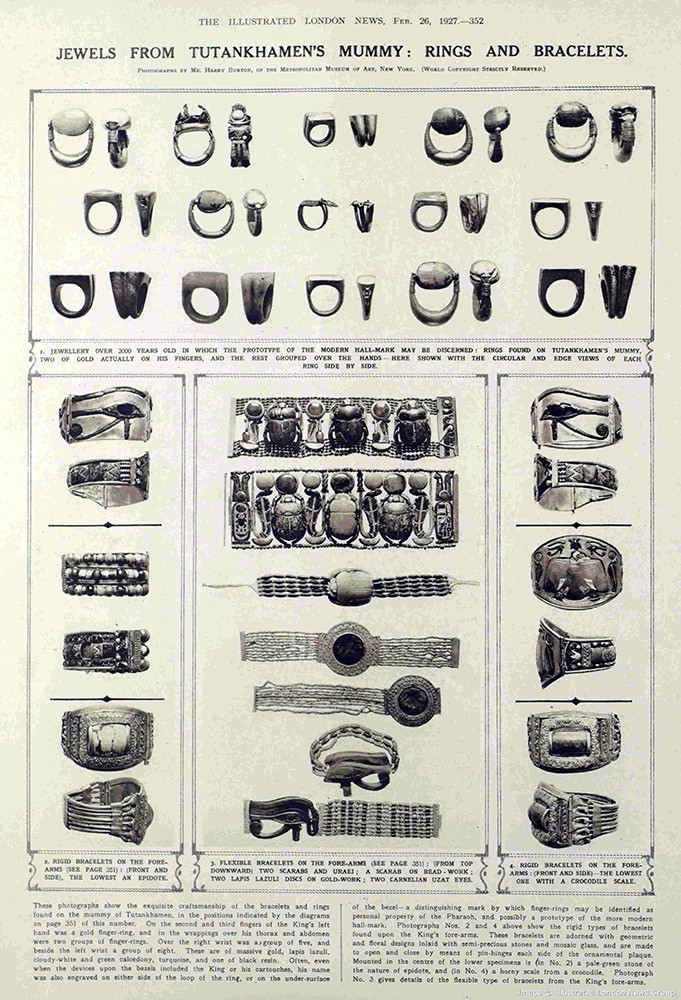

It is quite possible, by the sheer impetus of its popularity, that this fashion for Egyptian-inspired jewels would have continued undimmed into the Art Deco period. A tremendous boost was added with Carter’s 1922 discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun, thereby ensuring its enduring demand. The treasures found in the boy king’s tomb propelled Egyptomania into full-fledged hysteria. The apex of the style was reached c.1929, the year of the Cairo Exhibition. 1

Egyptian Revival Jewelers

Egyptian revival in jewelry was initiated in those heady days in Paris when Napoleon returned from Egypt with a treasure trove of design inspiration. The aesthetic was given additional impetus by milestones such as the raising of the Luxor obelisk in the Place de la Concorde, the building of the Suez Canal, decryption of the Rosetta Stone, and a plethora of other amazing discoveries. The apex of Egyptomania was achieved when Carter located the Tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922, the frosting on the cake. All this fuel for design inspiration provided jewelers the motivation to create jewels in the Egyptian taste for nearly a century, appeasing the vast appetite for all things Egyptian.

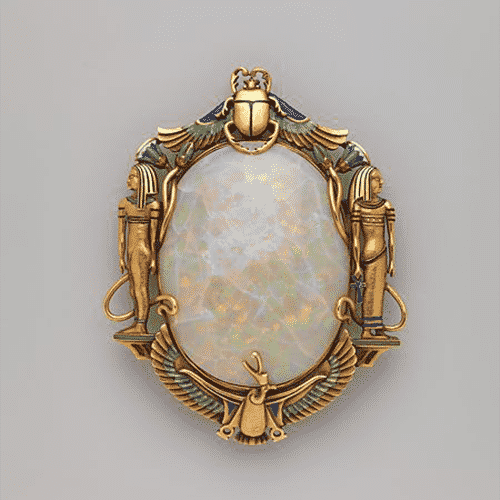

Castellani admired and understood the work of the ancient Egyptians however, his Italian clientele did not love the style the way they adored the revival jewelry based on discoveries in their own region of the world. Therefore, Egyptian-style jewelry by Castellani was very rare. Giuliano, however, enthusiastically worked in the style c.1860-1895. He collected articles of faience and scarabs to mount as jewels and also created enamel and gold items using hieroglyphs and other ancient writings for design inspiration, along with polychrome enamel works that resembled Egyptian intarsia jewels.2

Tiffany & Co. brought their own unique style to the Egyptian revival. Known for their use of Favrile glass in jewelry and decorative objects, they cast iridescent favrile glass “beetles” and set them into all manner of wearable art. They also produced jewelry that featured bits of Egyptian faience, scarabs, and other items along with gemstones, and gold beads.3

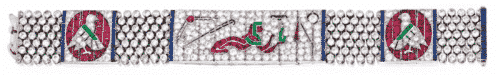

Van Cleef & Arpels too created a line of Egyptian Revival jewels. Their Art Deco contributions to the style were produced in platinum, encrusted with diamonds, and decorated by ruby, emerald, sapphire, and onyx depictions of Egyptian scenes and motifs. 5

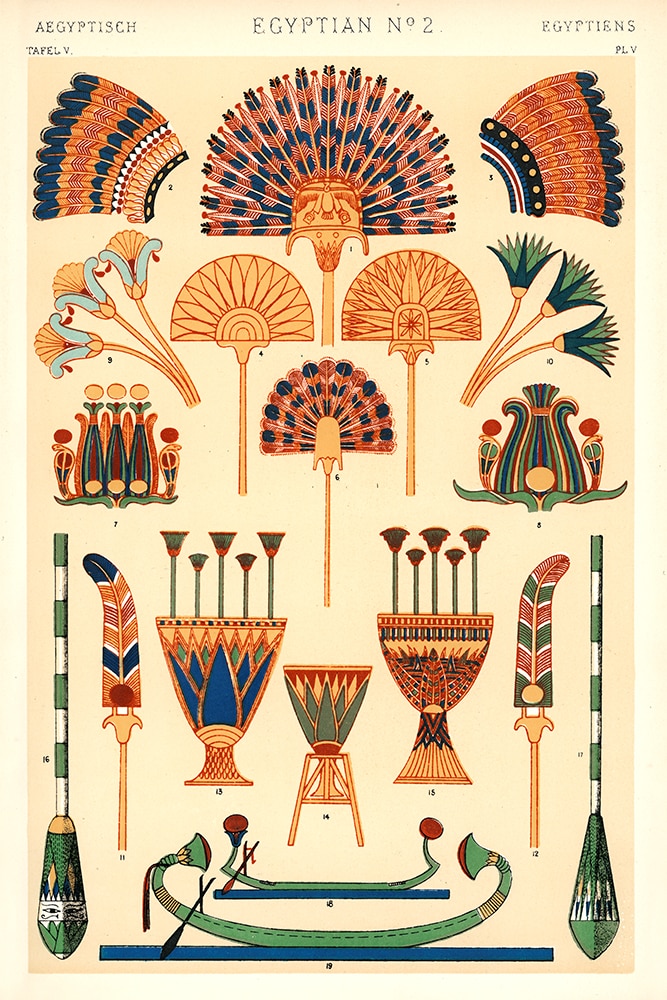

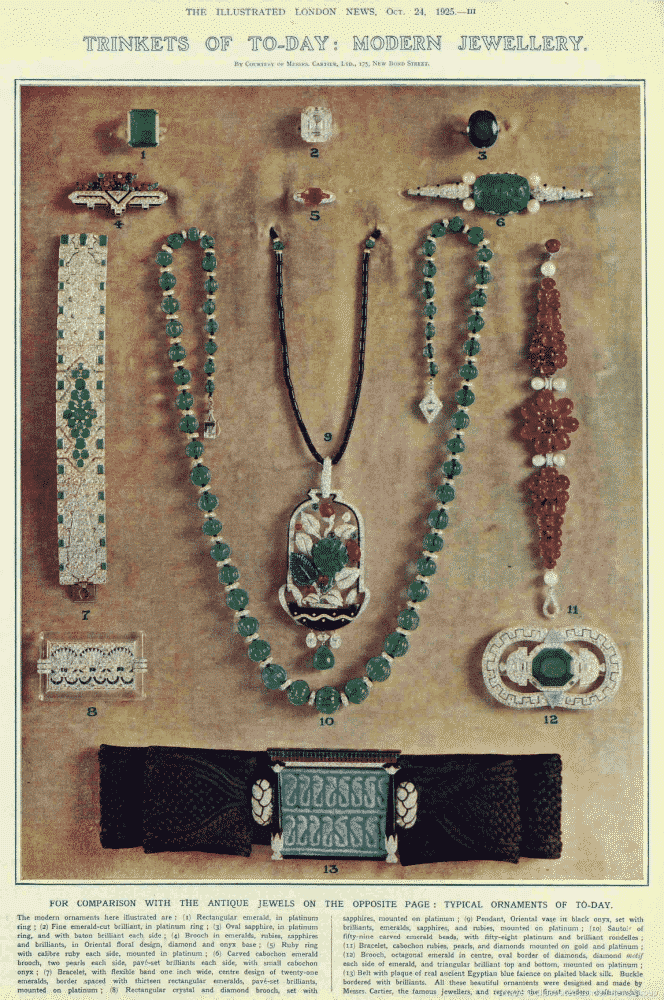

Cartier was probably the most prolific purveyor of the Egyptian motif. Beginning c.1910, long before the discovery of King Tut’s tomb, they created Egyptian-style jewelry by studying the major sourcebooks for inspiration. Description de l’Egypte featured an illustration of the temple of Khons at Karnak which is almost certainly the inspiration for the Temple Gate Clock. Design books commonly circulated among jewelers during this period and The Grammar of Ornament was no exception. This popular tome quite likely figured in many of Cartier’s Egyptian jewels that featured motifs of a similar style to those illustrated in “Grammar”.

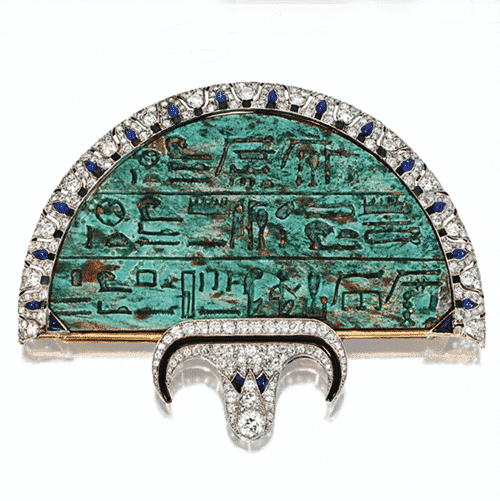

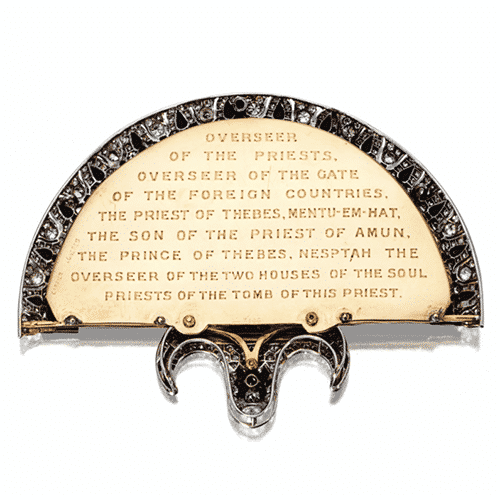

Another type of Egyptian-inspired jewelry employed by Cartier is a style that incorporates actual antiquities within the piece. Cartier struck up a relationship with Egyptian artifact traders in Paris and soon began to produce contemporary jewelry that included bits of actual antiquities. Placing these miniature treasures into settings with details inspired by actual flora, fauna, architecture, and figural images, and adding diamonds, gold, and other enhancements, created some incredibly unique jewels with a good deal of archaeological integrity. Designing elaborate settings to frame diminutive antiquities was popular up until the 1925 Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris. With the advent of the use of platinum in jewelry and the monotone color scheme of Art Deco, Egyptian-inspired jewels adapted. Cartier, among others, created the more two-dimensional Art Deco style jewels in onyx, diamonds, and platinum with Egyptian themes. Cartier continued to produce jewels in this manner until the onset of World War II.6

Sources

- Coffin Sarah D. Set in Style: The Jewelry of Van Cleef & Arpels: New York Smithsonian, Cooper Hewitt, 2011.

- Frelinghuysen, Alice Cooney. Nature Studies: The Art Jewellery of Louis Comfort Tiffany. In Phillips, Clare, Editor. Bejewelled by Tiffany 1837-1987 (pp.64-81). New Haven and London: Yale University Press in Association with the Gilbert Collection Trust and Tiffany & Co., 2006

- Mouillefarine, Laurence and Ristelhueber, Véronique. Lacloche Joailliers. Italy: OGM, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Éditions Norma & L’École des Artes Joailliers.

- Munn, Geoffrey C. Castellani and Giuliano: Revivalist Jewellers of the 19th Century. New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1983.

- Nadelhoffer, Hans. Cartier: Jewelers Extraordinary: New York, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1984.

- Nicholls, Dale Reeves; with Foote, Shelly & Allison, Robin. Egyptian Revival Jewelry & Design. Atglen, PA, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2006.

- Rudoe, Judy. Cartier 1900-1939. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1997.

- Vever, Henri, Purcell, Katherine (translator). French Jewelry of the Nineteenth Century. Paris, France: H. Floury, 1906-1908 – Reprinted: London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd., 2001.