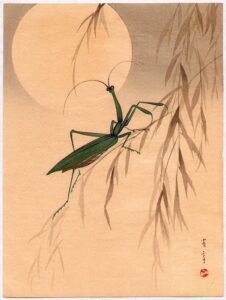

Watanabe 1851-1918.

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, there were many forces at work in the world of decorative arts that would propel artisans out of the humdrum and into the incredible. A marshaling force for inspiration in the arts was the reopening of the trade routes with the East in 1858. The Japanese were invited to participate in the 1862 International Exhibition in London and the Japanese prints and woodcuts, with their simple yet elegant interpretation of nature, had a profound influence on those looking for a new aesthetic. Japonisme, as it came to be called, provided the antidote to the fussiness of Victorian Era design that the new craft movement was searching for. Jewelers soaked up the Japanese bond between nature and design, its simplicity of form, the intense use of color, and the concept of mixed metals, giving birth to an entirely new decorative style.

The revolution that sparked the Arts and Crafts Movement in England arose from dissatisfaction with shoddily made and design deficient machine-manufactured goods. The Movement’s artisans advocated the inclusion of art into everyday objects thereby providing a place for art in our daily lives. The promotion of self-expression by this movement resulted in guilds and cooperatives that provided an environment to nurture this burgeoning revival of creativity. In France, Europe, and the United States, the Arts and Crafts Movement provided a framework that supported emerging new ideas in the arts, especially jewelry and metalwork. This movement toward handcrafted goods, in combination with the emerging Japonisme, were the ingredients that would blend together and become Art Nouveau.

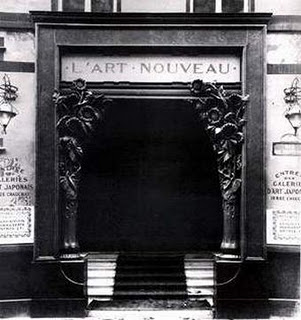

In Paris, art dealer Samuel Bing rechristened his revitalized Asian art gallery “L’Art Nouveau” inadvertently giving the new aesthetic a name. In 1895 Bing created, in essence, an international exhibition to celebrate the re-opening of his gallery. He brought together many of the artists that would form the core of the Art Nouveau movement. The opening of L’Art Nouveau showcased all types and styles of decorative objects including; Tiffany favrile glass, Gallé glass, and items in a variety of decorative arts by Lalique. The Société National des Beaux Artes, L’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, the Société des Artistes Français and others had been encouraging and supporting this revolution for some time, but it all came together, albeit in a somewhat mismatched conglomerate, at Bing’s gallery.

Having laid the groundwork for his new venture, Bing set out to create an Art Nouveau pavilion for the 1900 International Exhibition in Paris. Bing personally supervised the work, using artists he felt suited his interpretation of the ideal – Edward Colonna, Georges de Feure, and Eugene Gaillard.

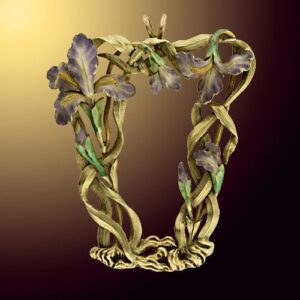

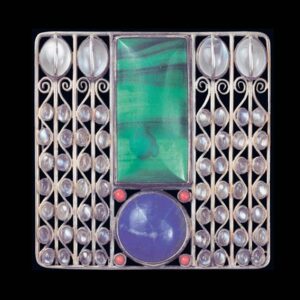

A predominant theme emerged in Art Nouveau design; the free-flowing line. Sometimes referred to as the “whiplash” line, it was used to suggest movement and was an interpretation of the shapes and lines found in plants, a woman’s hair, feminine curves; essentially everything that moved waved and undulated in nature. The way in which this line was employed came to define the characteristics of Art Nouveau as it manifested itself in various countries. In England, it appeared as a Celtic revival flowing through squares, triangles, and knots. The French had a figurative approach, using “the line” to define a woman’s hair or the movement in a plant. Other cultures used it to create free-flowing abstract designs.

“The importance of the melodious line was expressed by Walter Crane: ‘Line,’ he wrote, ‘Is all important. Let the designer, therefore, in the adaptation of his art, lean upon the staff of line – line determinative, line empohatic, line delicate, line expressive, line controlling and uniting'”1

Various themes and motifs were recurrent in Art Nouveau jewelry. Insects as fantasy creatures, especially dragonflies and butterflies, were interpreted in a myriad of ways and mediums. Plique-à-jour enamel was particularly suited to provide color, light, and life to the gossamer wings of these fascinating creatures. Beetles, grasshoppers, spiders and other insects also inspired the jewelers working in the Art Nouveau aesthetic. The Victorian serpent, coiled so meekly in mid-nineteenth-century jewelry, was reinterpreted with newly sensual movement, detail, and color. Other reptiles emerged from their earlier stiff and staid renditions newly alive with movement and glorious hues. Peacocks, with their magnificent plumage, preened anew with vibrant pigmentation and sinewy movement. Swans, swallows, and cockerels swooped and swirled playfully and sensually throughout Art Nouveau jewelry. On the darker side, bats, owls, vultures, grotesques and mythological creatures, fabulously embellished and menacingly rendered, added a fresh and chilling choice for personal adornment. For the less adventuresome, miniature landscapes combining many aspects of the natural world were also variously interpreted in jewelry.

The Victorians, other than in a mythological rendering or as a cameo or intaglio, had considered the decorative use of the female figure and face, objectionable. Art Nouveau jewelers, however, now reveled in the idea that the female form could be combined with elements from the natural world such as butterfly wings, and the resultant fantasy creature could soar with color and sensuality. These feminine fantasies appeared on diadems, brooches, bracelets, and rings. Once the bonds of Victorianism were overcome, a “cult of the female figure” ruled the design world. Changing roles for women in society inspired artisans. The beauty and accomplishments of great actresses and opera singers not only provided jewelers with inspiration but, by wearing these fresh new flamboyant jewels themselves, they helped propel the aesthetic into the new century.

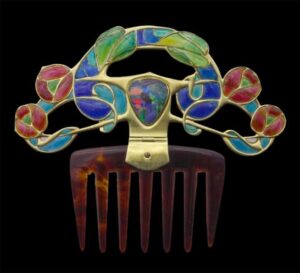

Art Nouveau jewelers were revolutionary in their choice of new mediums as well as in their uses for the old ones. Gold and silver were manipulated to a softness that seemed alive. Gems such as opal and moonstone, glimmering softly and mysteriously, suited the new look. Horn, bone, and ivory could be textured and sculpted into flowing with the “line” and thus became important elements. A rebirth and reinvention of enamel were critical in adding color and dimension to the work. Plique-à-jour enameling was rediscovered and used magnificently to create translucent natural interpretations of plants and insect wings, transmitting light and mixing in background colors, bringing the jewels alive. Champlevé enamel was masterfully applied in new ways to add depth and mystery. Pâte de Verre, a kind of glass that could be manipulated to a gem-like appearance, could be shaped and polished into all manner of objects and was used extensively throughout this period.

One of the most influential designers working in the Art Nouveau style was René Lalique (1860-1945). Although trained as a jeweler, Lalique worked in many different areas of decorative arts. Early in his career, he sold designs to the great jewelry houses of the period; Boucheron, Cartier, and Verver. Eventually, he produced his own designs to great success. As he began to experiment with enamel, Lalique became completely enamored with glass, a medium which he would eventually make his life’s work. After causing a stir in the art world with regard to the appropriateness of his theme, the use of the nude feminine figure was to become Lalique’s trademark. Needless to say, it was widely copied.

Henri Verver (1854-1942), another highly influential artisan in the Art Nouveau movement, brought his firm renown by producing the designs of others, primarily Eugene Grasset (1841-1917). Hair combs, exquisitely rendered in plique á jour enamel and pearls with organic motifs, were one of Verver’s great successes. The firm of Fouquet founded in 1860, would contribute to the Art Nouveau movement primarily through Alphonse Fouquet’s son Georges (1862-1957). Georges took the firm in a whole new direction using opals, enamel over chased gold and colored stones to produce his jewels. Another designer, Charles Desrosiers, joined Fouquet and designed some of the most magnificent jewels of the period. Collaboration with such important artisans as Alphonse Mucha and Etienne Tourette propelled the firm to new heights. Also working in Paris was Lucien Gaillard (1861-1933) specializing in plaques de cou, hair combs and pendants. Tremendously influenced by Japanese style, Gaillard worked often with horn, enamels, opal and colored stones in his designs. Patination eventually becomes his specialty.

The major jewelry houses each participated in the Art Nouveau movement in a slightly different way. Art Nouveau and the Edwardian style were evolving side by side in France and England. In a customer-pleasing effort, the major jewelry houses combined elements of each to create an entirely different sort of mixed jewel. Boucheron created very large pieces with high-quality stones that satisfied the criteria for both styles. Chaumet, Coulon, and Cartier all produced magnificent Edwardian jewelry with some crossover into the Art Nouveau aesthetic.

Specialization was the reason that French Art Nouveau jewelry rose to such superior heights of technical achievement. Enamel was one specialty that became characteristic of Art Nouveau jewelry and not all jewelers were proficient in the art. Often, enamelists worked freelance and were available for hire by any jeweler who needed their special skill. Quite a few of the jewels of this era were designed by an artisan, created by a jeweler, and finished by a specialist. Many of the major jewelry houses of the day hired out these various elements to workshops with the appropriate specialization.

Mass Production of small medals became a way to spread this jewelry to the masses. These medals were very popular and often relied on themes from antiquity, such as Greek and Roman gods and goddesses, feminine profiles, religious motifs, and symbols from nature. These miniature works of art were inexpensive to produce and therefore affordable to purchase. They took the form of brooches, pendants, buttons, stickpins, cuff links, and charms and were churned out in such large volumes that many of them exist yet today.

Art Nouveau existed in other countries in similar forms. In Germany and Austria it was referred to as Jugendstil. Art Nouveau/Jugendstil jewelry in Germany generally took its themes from nature. Flowers, along with other plants, were particularly well represented. The principle designers’ works were prolifically copied in lesser materials such as alpaca, copper, and glass but with excellent workmanship to create jewelry for the middle class. Theodor Fahrner (1868-1929) was a major producer of jewelry in this style. Drawing on the Darmstadt colony of artisans, Fahrner produced inexpensive jewelry for the masses from their avante-garde designs. In Austria, the most popular jewelry was created by the Wiener Werkstaätte under the design supervision of Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956). This workshop emphasized the interaction between the designer and those executing the design, thus ensuring the continuity of the design.

In England, the movement was an offshoot of the Arts and Crafts movement and exhibited a great deal of crossover with that aesthetic. Ironically, the most successful items produced in England were those that were mechanically reproduced, in direct opposition with the Arts and Crafts core philosophy. Liberty & Co. and Charles Robert Ashbee began to use machines to reproduce their jewelry circa 1900 and as a result, there are many of these pieces still available today. Archibald Knox introduced a stylized Celtic revival into Liberty’s line with great success, often enhanced by enamel and opal in silver and gold with a “faux” hand-hammered texture.

In the United States, the Art Nouveau movement could be found in jewelry designs that were mass-produced in Newark, New Jersey and Providence, Rhode Island. Small, inexpensive, commercially produced articles with an Art Nouveau design motif were created for the merchant class in abundance. Major American jewelry houses though created fine and unique Art Nouveau Jewelry. Tiffany & Company established the Tiffany Studios specifically to produce one-of-a-kind, handmade Art Nouveau pieces. Tiffany used unusual gems and baroque pearls with flowing lines and naturalistic motifs. Another prominent jeweler, Marcus & Co., produced a quantity of this Art Nouveau jewelry derivative of the French floral-themed jewels with extensive use of enamel.

The Art Nouveau style as it developed in France renewed jewelry creation as an art, incongruously, it was to be imitated ruthlessly around the world. What began as a revolution in the interpretation of design, drawing artisans from every discipline, ended up as a mass-produced product in an oversaturated market, attempting to meet the desires of consumers at all levels of society. The Art Nouveau movement drew to a close with the onset of war in Europe. The style was not picked up again until after the war but some of its design elements can be found in the Modernist Movement as it breaks through into popular culture c.1930.

Shop at Lang

French Art Nouveau Plique-à-Jour Pill Box

Medicate yourself in chic sophisticated style with this enchanting Art Nouveau pill box from turn-of-the-last-century France. Rendered in 18K yellow gold in exo…

SHOP AT LANG

Art Nouveau Brown Zircon and Diamond Dinner Ring

Here's something nouveau and different! Original Art Nouveau rings (circa 1900) are scarce enough, but a 1 1/8-inch-long dinner ring featuring an unexpected cen…

SHOP AT LANG

Art Nouveau Plique-a-Jour Enamel, Pearl and Diamond Lavaliere

Translucent apple-green petals, centered by tiny twinkling rose-cut diamonds, crown sinuous gleaming 18K golden stems in this stunning and quintessential Art No…

SHOP AT LANG

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Art Nouveau Jewelry, London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd., 1985.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Egger, Gerhart. Generations of Jewelry: from the 15th through the 20th Century, West Chester, PA: Shiffer Publishing, Ltd. 1988.

Notes

- Becker, p.15↵