Photo Courtesy of Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Tiaras have been worn by royalty and commoners alike and, while they symbolize wealth and rank, they are not necessarily an emblem of monarchy like a crown. The design of a tiara is usually semicircular and can be worn on the head in many ways, including low on the forehead or sloping from the top of the head to just over the ears. By contrast, a crown is circular and sits atop the head and surrounds the entire circumference. Both crowns and tiaras are adorned with gems and are made from precious metal but symbolically they are separate and distinct head ornaments. Monarchs can and will wear tiaras, but someone who is not a head-of-state will not appear in a crown. The evolution of the tiara began alongside side that of the crown, in ancient times, and continues on into the twenty-first century.

Antiquity

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Since the rise of humankind, we have sought ways in which to decorate and beautify ourselves by wearing items we find attractive. The desire to adorn one’s head with beauty first manifested itself in the creation of wreaths of foliage and flowers. Eventually, these plants began to take on deeper symbolism. In ancient Greece, at the Olympics, the victors were crowned with olive wreaths. Laurel wreaths were presented to champions and myrtle served to symbolize newlyweds. Figures throughout mythology were depicted wearing laurel wreaths. Firmly ingrained in our history, the laurel wreath continues to symbolize scholarship by being awarded to Master’s Degree graduates and the term Laureate refers to those awarded a laurel wreath, such as the Nobel Laureate. The motif continues to be applied in architecture, the arts and graphic design. Military emblems, pins, and many other such items often depict a wreath to this day.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

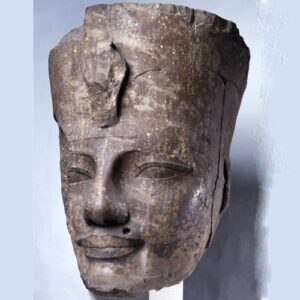

All the symbolism and culture associated with the awarding and wearing of botanical wreaths was translated to a more fixed medium when we began to smelt and refine metals. Through the study of ancient paintings, tapestry, and sculpture, we can see that wreaths soon evolved into crowns, tiaras, and diadems. Few of these ancient tiaras have survived for us to study, but the evidence of their pervasive use is irrefutable. The ancient Egyptians are a prime example. The Egyptian crowns were many and varied in design, shape, and color, their symbolism was critical both politically and religiously. Many artifacts from the ancient Egyptian civilization can be dated and identified by interpreting the crowns depicted on them, as different crowns were favored during different periods.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

The term diadem is from the Greek diadein – to bind around. Early Greek diadems were basically renderings of their botanical predecessors in gold, as bands with pediments. Such wreaths were used to adorn shrines and temples and were designed to follow the symbolism of particular gods: ivy denoted Dionysus, laurel for Apollo, wheat for Demeter, goddess of prosperity, olive branches for Athena, myrtle for Aphrodite, and Oak for Zeus. The Etruscans created a more traditional diadem, while the Scythian created a stiff halo-like headdress that evolved into the kokoshnik. The term tiara is of Persian origin and denoted the high headdresses that Persian kings wore in combination with a diadem

Photo Courtesy of National Archaeological Museum of Greece.

The Romans, while emulating the Greeks, were not as skilled in their designs. They were, however, ultimately responsible for the addition of gemstones to enhance the traditional leaves and flowers on diadems and tiaras and they solidified the tiara as an image of imperial authority. Women of rank were rendered in portraits and sculptures wearing golden bandeaux, wreaths, and halos. The fall of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity combined to drive the wearing of diadems, tiaras, and crowns from fashion. The ancient world became to be looked upon as immoral and all association with it was frowned upon. Tiaras continued to be depicted in art but not actually worn.

Medieval Tiaras

Medieval society set great store by the wearing of head ornaments. Royalty wore pinnacled coronets and rings of leaves, plants and flowers and the dowries of wealthy brides included a jeweled coronal or garland as part of their wedding attire. These ornaments remained popular until the sixteenth century when the aigrette and billiment rose to fashion heights.

Art from this period was disparaged as primitive and, as there was no sense of historical preservation, much of the secular art of the Middle Ages was lost. We are left, overwhelmingly, with religious-themed art that doesn’t necessarily depict society and its attire. One of the few remaining artifacts, The Iron Crown of Lombardy has become the symbol of medieval Italy. There is a narrow band of iron, about three-eighths of an inch wide, on the inside of this crown that is said to have been forged from one of the nails used at the crucifixion of Jesus.

18th Century

Late in the eighteenth-century tiaras returned and the emphasis changed from goldsmith’s renderings of naturalistic botanicals to gem-set creations that were all about the stones, their size and value, and not about the gold work. Classical motifs, scrolls, and hearts alongside natural themes were popular, but this time rendered in diamonds and gemstones. The tiara came to be the most important symbol of wealth and rank for English women and its popularity continues today.

19th Century

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Napoleon, emulating the style of Imperial Rome, ushered in the neoclassical revival. When he crowned his first Empress with a tiara as a symbol of sovereignty, the design was a neoclassical laurel wreath rendered in diamonds. Bonaparte saw to it that his entire court linked itself to ancient Rome with classical motif tiaras of laurel, spirals, Greek-key patterns and the like. A popular tiara design included the use of ancient cameos and intaglios depicting classical scenes. One of these created for Josephine raided the royal collection of eighty-six ancient cameos to secure enough for a parure for the Empress. This style was imitated in a plainer version set with contemporary cameos for the less well-to-do.

Napoleon’s second wife, Habsburg Archduchess Marie Louise received even more spectacular jewels and parures that always included a tiara. Women invited to court were expected to adorn themselves similarly and tiaras were considered the best way to display one’s wealth. When the Bourbon monarchs were restored to the throne the custom of wearing tiaras continued.

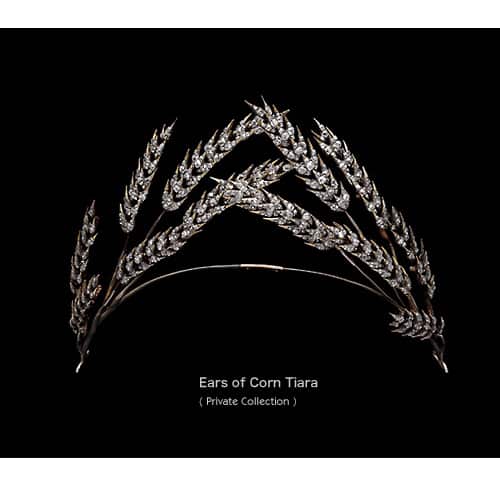

After the English defeated Napoleon at Waterloo, suites of jewelry for English women also included a tiara. While the classical designs remained, the naturalistic designs of the eighteenth century also returned to popularity in the form of garlands, flowers, bouquets and bows.

Following the death of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria entered a prolonged period of mourning. The influence of mourning on jewelry was widespread. Jet, Berlin iron, cut steel and black enamel were the materials used to create mourning jewelry. Parures, including matching necklace, earrings bracelet, and tiara, in these subdued materials and black color, were considered crucial for the royal or wealthy women of this era.

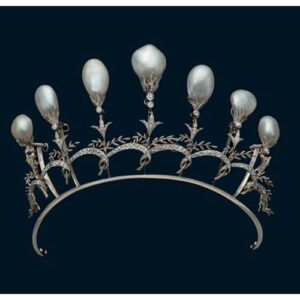

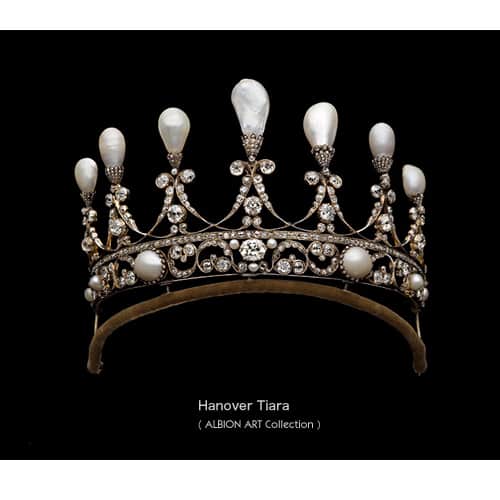

© Albion Art.

In France, the Revolution had put an end to rich displays of jewelry. With Napoleon III as emperor and his marriage to Eugenie de Montijo in 1853, the grandeur of the court in France was revived. The empress was the recipient of the remodeled crown jewels and she led the way for a revival of tiaras and parures of magnificent jewelry in France. In 1870 when the Third Republic was established in France, the tiara was once again relegated to private events. Publicly, aigrettes and combs were the fashion.

Elsewhere in Europe, magnificent jewelry for the royals was the order of the day. Elaborate creations rendered by jewelers at the height of their craft were seen in every country. International exhibitions featured jewelers and their splendid creations, with the tiara firmly in the place of honor. The designs ranged from national emblems to symbols of rank or family badges and the ever-popular return to the naturalist themes of the past. The discovery of diamonds in Africa fueled demand for diamond set tiaras and parures. The introduction of electric light-reinforced glittering diamonds as a popular choice.

In Russia the displays of opulence were unrivaled. Fashion dictated matching gems for every gown. The kokoshnik (translation cockscomb) a head-dress from Russian traditional folk costume and worn since antiquity, inspired two tiara styles: the halo and the fringe (often referred to as a tiara Russe). These styles swept Europe, having a universal influence on tiara design. Even after the Revolution of 1917, this style continued to be made in Paris by Cartier for another ten years.

20th Century

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

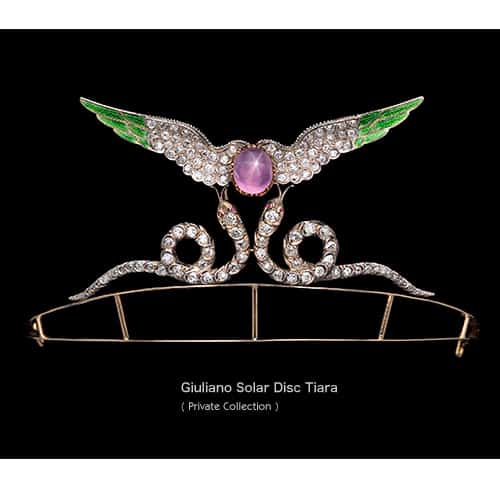

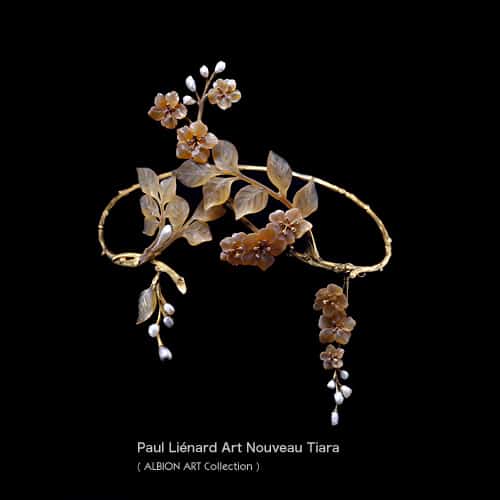

In the early twentieth century, two artistic styles were emerging in decorative arts and jewelry, the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau. Tiaras were not immune to these stylistic changes and the results were some very unique and interesting tiaras. A renewed interest in nature and new techniques such as plique-á-jour enamel, carved horn, and bone, resulted in amazingly lightweight head ornaments with incredible artistic appeal.

At this same time, the introduction of platinum allowed jewelers to create lacy feathery tiaras with little metal showing. At the court of Edward VII tiaras were more prevalent than ever and this trend combined with the use of platinum resulted in a redesigning of the family jewels, setting them into these new airier designs. The hairstyle of the day, the pompadour, gave these tiaras a good foundation. As the world began its preparations for a World War, the tiara disappeared and the narrower, less showy, bandeau and aigrette again took its place.

During the period between the World Wars, the tiara began to reappear. Tiaras were worn to formal parties, balls, the opera and other major social gatherings. Again the designs were borrowed from nature with laurel wreaths, vines, flowers and the like leading the trend. The roaring 20s ushered the bandeau back into popularity and saw the use of carved gems, and geometric shapes, typical of the jewelry period we now call Art Deco. Jewelers began to supplant the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts styles with these geometric motifs that were more in line with the age of machines. Unprecedented versatility was designed into tiaras so that they could be disassembled and the pieces worn in a variety of ways. In addition, the short hairstyles of the day forced jewelers to come up with innovative designs that would allow their creations to be worn without the supportive hairstyles seen up until that time.

The stock market crash in 1929 put many jewelers out of business and displays of wealth became rare. Tiaras were still worn by brides and royalty but American socialites were no longer flaunting their wealth. In Europe, the wealthy who wished to remain fashionable began ordering their jewelry set with less valuable gems like aquamarine and topaz. The coronation of George VI in 1937 ushered in a revival of extravagant jewelry and tiaras, but it was short-lived. The onset of World War II put an end to the social events where lavish displays of jewelry were necessary.

The post-war mid-twentieth century saw luxury come again into vogue. The wealthy and the royal dusted off their jewels and proudly displayed them anew. Brides continued to include tiaras as an important part of their wedding wardrobe. Jewelers were again put to work resetting gems to reflect current fashion. New wealth from the Middle East increased demand for jewelry of all kinds, including tiaras. The design emphasis switched from displaying rank and wealth to decorative elements. Major gems began to be worn in necklaces, rings and earrings instead of as centerpieces on a tiara. In America, women of wealth were vying for the jewelers’ attention demanding the latest in jewelry fashion which included tiaras.

By the late twentieth century, the wearing of tiaras became the purview of royalty. Women of wealth continue to wear tiaras occasionally, for extravagant events, but it is not the “requirement” it once was. Brides, however, have not given up their right to be “Queen for a Day” and continue to keep tiaras in fashion for their special time. A renewed respect for the designs of the past has helped save some of these magnificent creations from redesign so that we may enjoy their beauty in museums and on the heads of royalty into the future.

Related Reading

Sources

- Dunn, Jimmy. Crowns of Ancient Egypt, an Introduction. © 2010. (http://bit.ly/1E4Llt8)

- Munn, Geoffrey. Tiaras: Past and Present, London: V&A publications, 2002.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Tiara, Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2000.