The Aesthetic Period of Victorian jewelry can be defined as one of reaction against previous jewelry periods. Victorians became disillusioned with fashions and furnishings and sought a way out of the conventions of the past, moving toward a time of more refined artistic taste. William Morris was doing his best to keep the spirit of the Middle Ages alive in spite of the industrial revolution. In 1884, following Morris’ example, a group of craftsmen formed the Art Workers’ Guild. In 1886 a group of artists formed the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society and together these two groups set out to woo the public with their work.

The Gibson girl hairstyle depicted in 1890 in drawings by Charles Dan Gibson portrayed women in this new light. The “Gibson Girl” was independent, fun-loving, self-aware and self-assured. Hair combs, often carved from tortoise shell and embellished with gemstones, were essential accessories for this “modern” coiffure. New sporting activities for women, such as bicycling and golf, led to dramatic feminine wardrobe adjustments. Keeping the hands free, long chains held coin purses, watches, and lorgnettes. Whistle bracelets were a must for ladies who took long rides by themselves allowing them to summon help from a two-mile radius.

Women were increasingly involved in the business world. Working in politics they founded the Primrose League in 1885 and the Women’s Liberal Federation in 1886 working furiously toward achieving the right to vote. Young women were going to college and taking an active interest in sports and leisure activities. Fashionable women wanted to achieve the impression that they were a bit naughty or frivolous thus showing the world they were modern or fin de siècle.

In spite of these new jewelry necessities for the modern Victorian woman, in general, women wore much less jewelry and very little during the day. Diamonds were perceived to be in poor taste during daylight hours. In 1890 the Jewellers’ Association, fearing that women had abandoned jewelry altogether, appealed to the Princess of Wales for her help. She purchased a few things and tried to set an example, but dress balls and the opera were the only occasions that brought out any display of jewels at all.

Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Throughout the 19th Century, international exhibitions played a major role in introducing the public to innovations in art and industry. Celebrating the 400th Anniversary of the discovery of America, Chicago hosted the 1893 Colombian Exposition. The highlight of the show was electricity. Visitors to the show were awestruck by fabulous, illuminated displays by some of America’s top designers like Tiffany and Gorham. Case after case of Victorian chains, rings, bracelets, earrings, and watches were met with great enthusiasm. The jewelry was lighter and on a smaller scale than in previous years. Weighty Victorian brooches were replaced by smaller pins scattered on the bodice of a dress and diamond brooches were often worn in the hair for evening. Small stud earrings were desirable as the latest Victorian hairstyles exposed the ears.

The new generation of jewelry designers was appalled by the blatant copying of historic jewels and the heavy-handed creations of their predecessors. They sought to break with the tradition of imitative jewelry and create something completely new. Soft curves and natural shapes with more delicate coloring were the result of this overreaction to the past. Gemstones were cut en cabochon with a preference for amethysts, emeralds, and opals. C.R. Ashbee, a leader in the Arts and Crafts movement, was one of these new designers. Coming from the belief that jewelry should be designed for its intrinsic beauty and not its intrinsic value, Ashbee used pink topaz and amethyst set in dull silver or gray gold. Other jewelers followed suit.

The Art Nouveau style was developing in France during this period. Rene Lalique pioneered the use of feminine heads with long waving hair, soft colored stones, simple floral motifs and delicate enamels. He introduced fantasy and originality into his work and created a truly underivative style. In England, his work was perceived as the culmination of the new aesthetic that jewelers were striving to achieve. This made Lalique’s jewelry style an instant hit with the “new” Victorians.

A more conventional type of jewelry was still popular with many women of this era but there was a transformation of the style to a simpler look with a featured gemstone. Jewelers were specializing in providing a good selection of precious stones for their customers. Diamonds were still the preferred gem for special occasions and diamond rivières, tiaras, and bracelets set in silver-topped gold were the most popular items. This jewelry was more delicate than in previous eras and stones were set in a more airy manner reducing the metal as much as possible. In the late 1880s, advancements in jewelry manufacturing made platinum a viable metal for jewelry and it quickly became a favorite for diamond mountings. During the Boer War, near the end of the century, the supply of diamonds from South Africa was cut off and other gems regained some of their former popularity.

A design called a lace pin (a short bar pin/safety pin with a small design on top) along with bar brooches and delicate pendant necklaces were particularly popular decorated by shamrocks, stars (more dimensional than their previous iteration), knots and, most importantly, hearts. Some of these jewels were so small as to seem invisible, but they were “new” and that made them charming. The passion for novelty jewelry was still fueling the jewelry industry but, to keep it fresh, new designs were introduced. The “honeymoon” brooch was a favorite, designed as a bee perched upon a crescent moon. Other silly novelties included diamond chickens, jeweled lizards, frogs, and owls.

Those seeking this new aesthetic were influenced by a myriad of different events and people. Sarah Bernhardt, starring in Cléopatre, wore Egyptian motif jewelry with turquoise set in silver for the role. She was so popular that where she led, women followed, fueling a revival of Egyptian-styled jewelry. Jewelry from India also became popular after the eye-catching displays of this style at the Exhibition of 1886. English jewelers did not try to copy it as they had the work of the Greeks and Etruscans. The fact that this jewelry was entirely handmade with a lack of symmetry and precision appealed to those seeking something fresh. In an up-cycled jewelry trend that appeared c. 1885-1889, hand-pierced escapement covers removed from verge watches made circa 1600-1700s, originally designed to protect a watch’s balance wheel and staff, were re-purposed into earrings, bracelets, and pendants.

Jewelry of the Aesthetic Period

| HAIR ORNAMENTS & TIARAS | Tiaras were often necklaces with the ability to be attached to a fitted rigid frame so as to do double duty. Individual elements from these necklace/ tiaras could be removed and worn as pins and pendants. Russian styled tiaras with their spiky kokoshnik shapes were very popular in the 1890’s. Pins and brooches also doubled as hair ornaments securing chignons and curls along with tortoise and horn carved combs and hairpins. Miniature coronets or tiaras set on small combs and worn above the hairline at the center of the head adorned more than a few fashionable Victorians. |

| EARRINGS | From 1880 to 1890 earrings were fairly small, a single pearl for day and diamond studs in the evening. Pendant earrings re-appeared in the 1890s and were usually designed to move and catch the light and were studded liberally with diamonds. Screw back earrings made and appearance at this time and women were freed from having to pierce their ears. |

| BROOCHES & PINS | Brooches were small, delicate and plentiful. Quantity was definitely more important than continuity of design or theme. Elaborate star brooches, preferably set with diamonds, but sometimes with pearls, moonstones or opals, crescent brooches encrusted with diamonds and diamond-set sunburst brooches were the most popular. Gem-set butterflies, dragonflies, spiders, bees and flies along with enameled birds, violins, anchors, and arrows were in vogue. Frogs and lizards set with demantoid garnets and insects with plique-à-jour wings were other stylish motifs. Novelty and sporting brooches along with bar and feather brooches continued to flourish. Prince Edward’s love of horse racing ensconced the horseshoe as a good luck charm. |

| BRACELETS | Bracelets were worn in multiples, but instead of straps, bangles both wide and narrow clinked together decorated with diamonds, pearls, rubies, and sapphires. Sprung and hinged bangles and cuffs, as well as gold link bracelets, were fashionable. Bangles composed of multiple wires topped with a flower, scroll or geometric motif and velvet ribbons with diamond openwork slides predominated. |

| NECKLACES | Necklaces took on a fringed appearance and graduated rows of diamonds dangled from a delicate chain. Diamond necklaces designed as a series of flowerheads joined by foliate motif links and suspending diamond set chain swags displayed the new delicacy. Victoria’s daughter-in-law, Alexandra, was setting fashion trends long before she became Queen. The collier de chien French style dog collar necklaces she wore to conceal a scar were an instant success in England and America. Other necklaces were combined with the dog collar including strands of pearls and diamond riviére necklaces. Both long sautoirs and chokers remained popular into the next century. |

| PENDANTS & LOCKETS | The brooches of this period were often outfitted to do double duty as pendants. Crosses and hearts were the essential pendants for every "modern” Victorian woman. Hearts were often enameled in red green or blue with a central pearl or diamond. Lockets were smaller, generally, round with a monogram or set with a small gemstone. Longchains suspending a watch or lorgnette, often with enamel decoration, appeared around this time. |

| RINGS | Circa 1895 the earliest examples of Victorian solitaire diamond rings, set in both gold and silver appeared. Discovery of diamonds and gold in South Africa were the impetus for the popularity of these rings. Crossover rings defined the period. A pair of diamonds, a diamond and a ruby or sapphire, two pearls, crossing in the center, with scrolled shoulders are still in vogue. Class rings and association jewelry became a thriving business. Multi-hooped rings with a small gem-set motif perched in on the top with a heart, crown or ribbon motif was a popular style held over from the eighteenth century. |

The End of an Era

The extended Royal Family maintained their influence on fashion. The dog collar-style necklaces and ropes of pearls worn by the Princess of Wales were emulated throughout the globe. Upon the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, Edward and Alexandra would continue to set the style for the next era of jewelry and fashion.

Timeline

Late (Aesthetic) Victorian Period

General History

- Statue of Liberty dedicated.

Jewelry History

- Richard W. Sears starts a mail-order company to sell watches (second company to sell jewelry and watches founded in 1889).

- Tiffany setting for diamond solitaires introduced.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Hall-Héroult process for refining aluminum developed; first commercial production in Switzerland, value drops.Celluloid photographic film invented by Hannibal W. Goodwin.

- Gold extraction by cyanide process Invented by John Stewart, Macarthur and the Forrest brothers.

- The Belais brothers of New York begin experimenting with alloys for white gold (c.). David Belais introduces his formula to the trade in 1917 (18k Belais).

Jewelry History

- Tiffany & Co. purchases the French Crown Jewels.

- Birmingham (England) Jewellers’ and Silversmiths’ Association formed by manufacturers.

Jewelry History

- C.R. Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft founded in London, the first crafts guild to specialize in jewelry making and metalwork. <

General History

- Paris Exposition Universelle – Eiffel Tower constructed.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Black Opals discovered in NSW, Australia; commercial mining at Lightning Ridge begins in 1903.

Jewelry History

- René Boivin establishes Boivin in France.

- Tiffany & Co. exhibits enameled orchid jewels by Paulding Farnham at the Exposition Universelle.

General History

- Gibson’s Gibson Girl appears in Life magazine.

General History

- The marking of foreign imports with the name of the country of origin in English required by the enactment of the McKinley Tariff Act, October, 1890.

- Patent for artificial horn (celluloid).

Discoveries & Innovations

- Frémy publishes experiments with ruby synthesis, drawings of synthetic-set jewelry.

- Power driven bruting (girdling) machine for cutting diamonds patented in England.

- First commercial opal mine opened in Australia.

Jewelry History

- Marcus & Co. formerly Jaques & Marcus, established in New York.

- Vogue magazine founded in the USA.

General History

- World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Excelsior Diamond is found in South Africa.

- Cultured pearls first developed by K. Mikimoto in Japan; first spherical pearls grown 1905.’Platingeld’ introduced, used for simulated gold and platinum chains.

General History

- Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope Parlor (‘peepshow’) opens in New York City.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Cross & Bevean, UK, issued patent for cellulose acetate

Jewelry History

- Screw back earring finding for unpierced ears patented.

General History

- American Consuelo Vanderbilt marries the British Duke of Marlborough.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Bonzano Creek Gold Rush in Klondike, Yukon, Canada.

- The wireless telegraph invented by Guglielmo Marconi (first transatlantic wireless signal in 1901).

- Blue sapphires discovered in Yogo Gulch, Montana.

Jewelry History

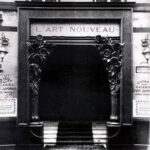

- Sigfried (aka Samuel) Bing opens his new Paris gallery of decorative art called L’Art Nouveau.

- René Lalique exhibits jewelry at the Bing gallery and the Salon of the Societé des Artistes Français; begins work on a series of 145 pieces for Calouste Gulbenkian.

- Daniel Swarowski opens Glass stone-cutting factory in Tirol, Austria.

General History

- Queen Victoria‘s Diamond Jubilee.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Casein plastics marketed in Germany.

Jewelry History

- Lacloche Frères established in Paris.

- Boston and Chicago Arts and Crafts Societies founded.

General History

- Spanish-American War.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Alaska Gold Rush.

- Commercial sapphire mining begins in Rock Creek, Montana.

- Commercial tourmaline mining begins in San Diego County CA.

General History

- Boer war in South Africa starts, lasts until 1902.

Jewelry History

- Aigrettes reach the peak of their popularity (c.)

- Diamond supplies curtailed by the Boer war, prices for De Beers’ reserve stock rise.

General History

- Paris Exposition Universelle.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Oxyacetylene torch invented by Edmund Fouché.

- The diamond saw is invented by a Belgian working in the USA. (c.1900)

- Synthetic rubies exhibited at Paris Exposition.

Jewelry History

- Tiffany & Co. exhibits a life-size iris corsage ornament set with Montana blue sapphires.

- Boucheron, Fouquet, Lalique, Vever and other French jewelers display their Art Nouveau jewels at the Paris exposition.

- The Kalo Shop founded by Clara Barck Welles in Chicago, IL begins jewelry making in 1905, closed in 1970.

- USA officially adopts the gold standard with McKinley’s signing of the Gold Standard Act.

More Victorian Jewelry

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery: Second Edition: Colchester, Essex, N.A.G. Press Ltd., 1987.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.