Byzantine jewelry was a full continuation of the Roman traditions which were kept alive behind the high walls of the new capital, Constantinople. The Roman techniques and styles continued to form the foundation of Byzantine goldsmith‘s skills who weren’t complete copycats; some innovations such as the use of Christian iconography and further specialisation of new and old techniques occurred. Production in the old jewelry centres of Alexandria and Antioch gave way to increased production in Constantinople. Byzantine jewelry had a huge influence on the manufacturing of personal decorations in the rest of the Medieval world. The Carolingian (start 742 AD) and the later Ottonian courts (start 962 AD) were linked to the Byzantine Empire and adopted their fashion resulting in the northern European Romanesque jewelry style.

In the Byzantine Empire jewelry played an important role. It acted as a way to express one’s status and as a diplomatic tool. In 529 AD Emperor Justinian took up laws regulating the wearing and usage of jewelry in a new set of laws, later to be called the Justinian Code. He explicitly writes that sapphires, emeralds, and pearls are reserved for the emperor’s use but every free man is entitled to wear a gold ring. This may tell us something about the widespread use and great popularity of jewelry. One could easily argue that there hadn’t been a need for such a law if jewelry had been a purely aristocratic phenomenon.

The Byzantine Empire was wealthy. It had gold mines within its borders and its geographical position was perfect for trade between the East and West. Successful traders, military officers, and high officials in the empire’s administration would all have been in a position to afford luxurious jewelry. In an attempt to keep jewelry exclusive Justinian ruled that only he got to decide who wore the finest jewels by presenting his favorite ‘servants’ with presents from the imperial workshops. It is important to note that the emperor’s monopoly didn’t mean that only a few high-ranked people wore jewelry, on the contrary, all other precious stones and gold, in general, were allowed to be worn. Items that are expected to be made in the imperial workshops have been found throughout the empire. These items could have been diplomatic gifts to local rulers or have been carried there on the bodies of military leaders and diplomats of the empire itself.

Materials

Just like in Roman times gemstones were extremely popular and the display of gems became more important than the surrounding goldwork. Precious stones came mainly from the East. Flourishing trading contacts with India and Persia brought vast amounts of garnets, beryls, corundum, and pearls to Constantinople. Gold was being mined within the empire’s borders in modern-day Greece, the Balkans, and Turkey, where silver was found with gold. The people of the Byzantine Empire liked their jewelry colorful. In addition to gemstones, the desired polychrome effect was achieved by the use of enamel.

Techniques & Styles

Gemstones were often were rounded (if not already done by nature), polished and then drilled. A gold wire would then be passed through the drill hole and bent into a loop on either side of the gem. This way the gemstones could be attached to one another to form necklaces, pendant earrings, headwear or bracelets.

Another typical Byzantine way of using gemstones was to cut them into polished cabochons and set them in collets. The gem became more important than gold in Byzantine times and less effort is put into gold surrounding big gemstones. The art of glyptography was kept in honor and cameos and intaglios were popular as ring stones and pendants.

Traditionally, motifs on gold were produced in a few ways: repetitive motifs were embossed on gold with the aid of a die, more individual work was chased and fine detail was achieved by engraving with a very fine-tipped tool. The Byzantine masters added and perfected the technique of highlighting such fine details in relief with the use of niello. Openwork had been popular in the Roman Empire and continued to be a favorite method of decorating goldwork in Byzantine times. Opus interrasile work became even more detailed and was used more elaborately than before.

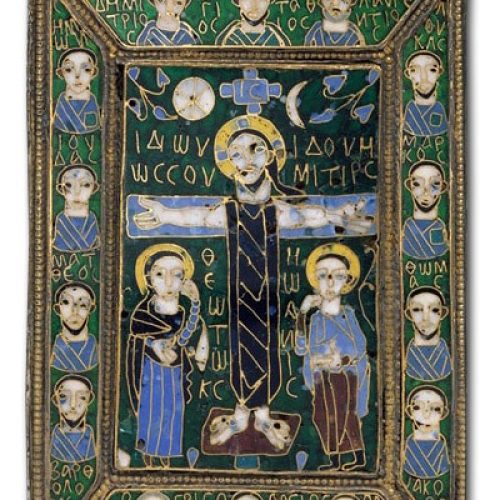

From the 9th century on the technique of cloisonné enamel found its way into the workshops of the Empire and quickly became a very popular appearance. The technique came from the West where it had developed into a widespread means of achieving polychrome jewelry earlier. The Byzantine jewellers became experts in the execution of this technique and used it a lot to depict saints.

Types of Jewelry

The typical Byzantine jewelry box would have been filled well. From headwear to earrings and necklaces to body chains, bracelets, and rings, just about every possibility to decorate one’s body was used. Large gem-set necklaces were in favor with the ladies while men wore pectoral ornaments, often coin based which may have served as military decorations or some other status symbol. Christian iconography in the form of crosses and enameled saint images used as pendants were a common sight. The classical loop-in-loop chains were substituted by linked (openwork) discs and/or linked gem beads as described above to form necklaces. Bracelets, often worn in pairs, such as the still popular snake bracelets or the new bangle bracelet with a hinge decorated the wrists of Byzantine women. Rings were popular and have probably been made everywhere in the empire. Sometimes with a stone, but often made of inscribed metal only. Large earrings are typical as well. Rather long pendant earrings and crescent shapes being the most popular.

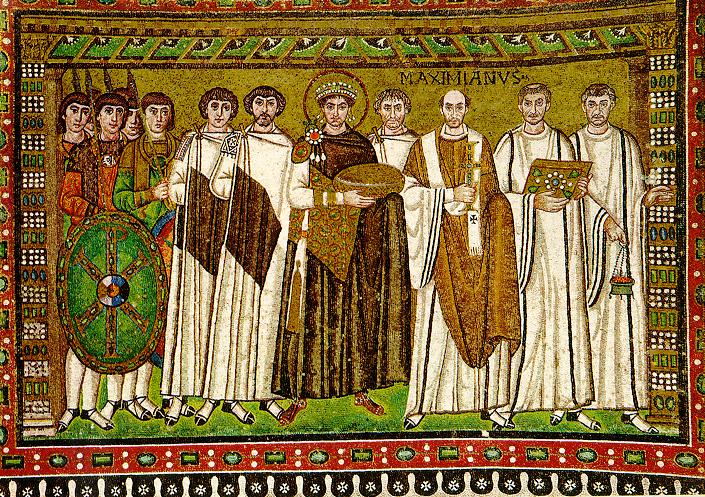

The Mosaics of the San Vitale

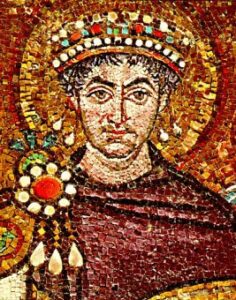

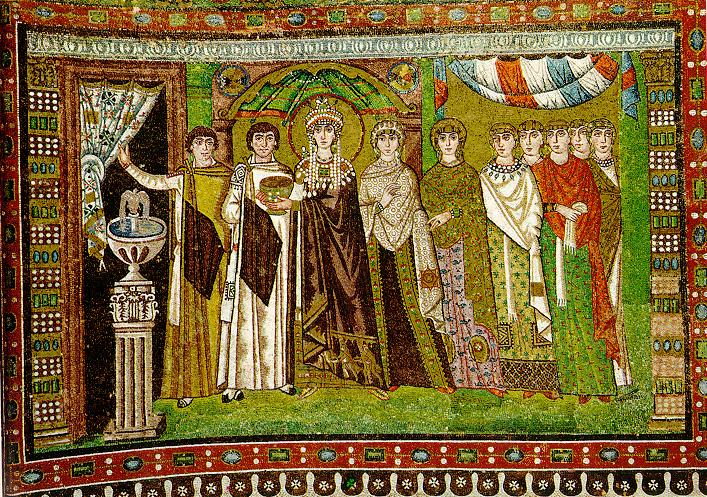

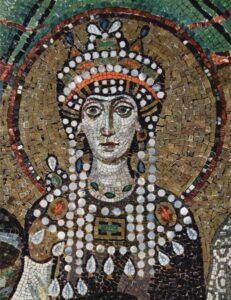

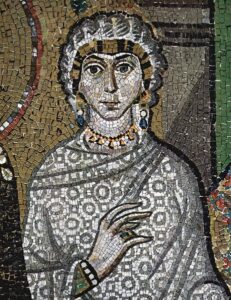

After the fall of the western Roman empire, the Italian city of Ravenna was in the hands of Germanic leaders until the Byzantine emperor Justinian defeated the Ostrogoths in 540 and conquered the city. He had a church built in the years after the victory called the San Vitale in which he ordered mosaics of himself and his wife Theodora to be made. These mosaics were completed in 548 and show us a glimpse of the rich court jewelry. Let’s take them under the loupe.

On the right is the detail of the emperor himself. He wears a brooch that seems to be featuring a bright red center stone set in a gold collet surrounded by pearls. The brooch has three huge drop-shaped pearls suspended from it by gold chains. Behind it, we see the blue of three fine sapphires and the green of what may be an exquisite emerald. On his head sits a golden crown, elaborately decorated with pearls and precious stones. His ears feature another form of pearl decoration, it’s without certainty that this is stated but it looks like 2 pairs of large drop shapes pearls are attached to one another and hung over the ears of the emperor. Compare the emperor’s ear decoration with that of the empress below and note the difference; her earrings have been explicitly depicted as being pierced through the lobe while Justinian’s aren’t and appear to be hung around his ears.

On the right, we see the detail of Empress Theodora. She is wearing a dazzling amount of jewelry. Her head is decorated with long strands of pearls hanging off a diadem of some sort which in its turn is decorated with sapphires, emeralds, and red precious stones, possibly rubies or garnets. She is wearing typical Byzantium pendant earrings with (from top to bottom) an emerald, pearl and sapphire; the three gems that were the emperor’s prerogative. Around her neck, she wears a gemstone necklace of drilled stones attached to each other with gold wire loops. The top of her dress is decorated with pearls, large emeralds, and red gemstones. Something that appears to be a garment fastener is visible over the empress’ right shoulder, featuring yet another emerald and a large pearl.

On the left, we see one of the court ladies wearing a golden diadem, pendant earrings that are very similar to those of the empress and a classical gold necklace. She is depicted holding up her right hand which clearly shows a gold ring with a gemstone. From under her robe a pearl bracelet and a golden bangle bracelet, set with emeralds, emerge.

The hand of another court lady is pictured to the right. Here another ring and bracelet, both set with gems, can be seen.

Sources

- Middeleeuwen, de Boer, D.E.H, van Herwaarden, J and Scheurkogel, J. Martinus Nijhoff uitgevers, Groningen, The Netherlands, 1995.

- 7000 Years of Jewellery, Various Authors, edited by Hugh Tait, British Museum Press, London, 1986.

- Ancient Jewellery: Interpreting the Past, Ogden, Jack, British Museum Press, London, 1992.

- A History of Jewellery 1100-1870, Evans, Joan, Dover Publications, Inc, New York, USA, 1953/1970.