Diamonds are the gemstone most commonly associated with engagement rings, but that has not always been the case. They first made their appearance in betrothal rings circa the fifteenth century but were not universally presented as betrothal/engagement rings until the seventeenth century. This is partly to do with the supply of diamonds, their affordability, and their popularity, or lack thereof. Until sufficient supplies of diamonds were available and techniques evolved that enabled them to be cut to maximize their brilliance and fire, they were mounted pretty much as they came out of the earth and worn only by those wealthier citizens who had access to the limited supply. Today the supply is more than adequate to provide diamonds to enhance every engagement ring and they are available in many shapes, sizes, and colors.

Although diamonds have a longstanding tradition of being the featured gem used for engagement rings, many other gems have also served as the central symbol of everlasting love. Among others, Sapphires, rubies, and emeralds have been conspicuously displayed in engagement rings, with or without diamond accents. Most famously in recent history was the sapphire ring presented by Prince Charles to his fiancée, Lady Diana Spencer, upon their engagement. Princess Diana picked the ring out herself from a Garrard’s catalogue. Diana’s son William continued the tradition by presenting his bride-to-be, Catherine Middleton, with his mother’s sapphire engagement ring. Colored gems can have deep and spiritual meaning to some and traditionally, they have also been thought to be suffused with amuletic and healing powers. This additional symbolism can enrich the significance of an engagement ring beyond a declaration of love to one of protection and strength.

All this power pent up in a ring makes its acquisition quite possibly the most exciting and terrifying purchase you or your perspective mate may ever make. So many styles to choose from: what metal, which gemstone, a matching wedding band… antique, modern???… questions spin endlessly. Sometimes there is a family ring to be resized, remodeled or traded in, but most often you are starting from scratch to pick out or design this outward sign of your love.

No other piece of jewelry is so deeply rooted in historical design sensibility as the engagement ring. An examination of the historical influences on engagement ring design often yields the answer to your design questions. Do you love Art Deco or are you a devotee of a more delicate Edwardian style? Should your ring be a replica of one worn by a historical figure or more practically, do you want your ring to be able to survive a trip to the gym and some serious gardening on the weekends?

In this time of “anything goes,” the choice of a modern sparkler or a historic beauty is up for grabs. There’s no wrong choice as far as fashion dictates, just the right choice as governed by personal preference and lifestyle. Highlights of the major design period originals and reproductions available for your “pop the question” presentation are detailed below.

Modern Engagement Rings

Contemporary engagement rings run the gamut from plain to elaborate and all increments in between. The emphasis has moved from the style of the setting to the cut of the diamond. The solitaire, a plain hoop with a specially selected diamond in any shape or color, optimized to produce the maximum brilliance and perched in delicate prongs (or bezel set) has come to be seen as the classic style. Since the 1950s this design has often included diamonds or gemstones flanking the central stone thereby subtly enhancing that crisp classic uncluttered look. A halo of smaller diamonds surrounding the central gem in a shimmering outline, and sometimes lining the shoulders or the entire ring shank, is a thoroughly modern design. Manipulating and splitting the shank itself into a myriad of shapes and undulating channels glimmering with pavé/micropavé or channel-set lines of diamonds provides another twenty-first-century look.

Retro Through Post-Ware Engagement Rings

At the close of the 1930s, with war approaching and platinum being reserved for the war effort, gold re-emerged as the metal of choice for jewelry, including engagement rings. Some countries banned jewelry manufacturing completely and in Britain, they allowed only “utility” wedding rings of 9 karat with a weight not to exceed two pennyweights. Gemstone rings featured larger less expensive gem materials and diamonds were scarce, mostly limited to those that could be culled from existing jewelry.

The end of the war allowed the jewelry industry to slowly ramp back up as the routes that gemstones traveled to market were reopened and precious metals were released from their wartime restrictions. In 1947 the De Beers ad slogan, ‘a diamond is forever’ cemented the diamond as the premier gemstone for engagement rings. Men returning from war were anxious to get back to a sense of normality and there were weddings galore. Modest diamonds were set in illusion heads to maximize their brilliance. Wedding sets were popular and yellow gold was still used for their construction with the illusion head in white gold to brighten the stone.

By the 1950s the jewelry business was thriving once again. Platinum was available and the “all-white” look for jewelry was all the rage. The combination of platinum and diamonds was irresistible and engagement rings were no exception. For the more modest budget, white gold filled the bill. Diamonds were featured more prominently in prong settings with a tasteful pair of side stones, or a discreet line of melee. The prongs were often large and incised to act as a modified illusion setting. Echoes of the Art Deco Era remained in the millegrained details and classic design elements.

Art Deco Engagement Rings

Abstract art and the clean, modernist design ideals of the machine age resulted in jewelry with a much more severe, geometric look. Jewelers of the day despaired at this lack of ornament, but little did they know that this aesthetic would remain popular for decades despite the changes in fashion and continuing innovation in the jewelry arts.

Art Deco engagement rings were usually composed of white metal (either platinum or gold) and diamonds. Innovation in the diamond and gem-cutting industries resulted in new diamond shapes, used both as central elements and as distinctive geometric accents, along with new shapes of calibré-cut colored gemstones. The innovative baguette-cut diamond was integral in creating the bold, angular look of Art Deco jewelry. Round brilliant-cut diamonds were used to pavé larger areas with baguettes used to define the edges and borders.

Alongside the classic platinum and diamond ring, another popular Art Deco aesthetic featured a surround or other symmetrical accent, of small colored stones that provided a punch-up to the “all white” look. Rubies, sapphires, emeralds and black onyx were all popular choices to use in juxtaposition with diamonds to accentuate the geometric aspects of Art Deco jewelry compositions. These timeless beauties are so distinctive as to be instantly recognized as quintessential Art Deco.

Edwardian Engagement Rings

The birth of the Edwardian aesthetic had its beginnings in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Jewelry styles moved from large and overstated to delicate at a very quick pace. The garland style that is a hallmark of the Edwardian period harkened back to eighteenth-century designs. Inspiration was taken from the ornamental motifs found in books and observable in situ on buildings, gates, monuments and in museums. Platinum replaced silver atop gold rings as the metal for diamond settings and eventually, thanks to the 1903 invention of the oxyacetylene torch, jewelry made of platinum without the gold underpinnings became possible.

Rings rendered in platinum took on a diamond-dotted lacey appearance. Millegrained and knife-like edges were possible, giving jewelry both textured and smooth mirrored accent possibilities. Pierced openwork fantastic designs rolled, scrolled and undulated in platinum and diamonds. The outbreak of World War I effectively ended the Edwardian Era, but designs changed little until after the war as jewelers and jewelry metals were put to work in the war effort. The Edwardian jewelry style persists in popularity and design influence more than one hundred years into the future.

In the book “Rings for the Finger” published in 1917, George Frederick Kunz wrote:

At the present time many platinum wedding rings are made perfectly plain, others are engraved with a laurel wreath as a peace or anti-divorce symbol, with oak leaves for strength, ivy for clinging devotion, and some other symbolic devices. Many alliance rings are made of two parts, one bearing the names of the engaged couple, the other the date of the engagement. Narrow gold rings with diamond settings are also used, closely resembling the type of diamond ring that has been worn as a guard-ring for many years.1

Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts Engagement Rings

Though not unheard of, true Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts engagement rings are rare. It could be that these rings have been lost through time and attrition or remodeled or recycled but whatever the reason, very few remain available on the estate and antique jewelry market today. The Arts & Crafts Movement eschewed the use of more expensive precious stones, such as diamonds, in favor of colorful cabochons highlighted by enamel. The metal of choice was usually silver or other white metal, with the occasional use of gold. While some of the rings made during this era may have served as engagement or wedding rings, there is no definitive engagement ring style.

The whiplash lines of the Art Nouveau era can be found in engagement ring styles. The use of gold (as well as silver) with sculptural effects that encompass the entire piece and the use of the undulating line are telltale design elements. Pastel-colored gemstones, as well as diamonds, are commonly included in Art Nouveau jewelry. This period was also known for the use of unusual materials such as horn and plique-a-jour enamel which were totally unsuitable for use in a ring that would be worn daily as an engagement or wedding ring. These design periods overlapped with Victorian and Edwardian Eras making it more likely that engagement rings from that time would fit design elements of those categories more readily.

Victorian Engagement Rings

The rising middle class, with its disposable income, ascended as a result of the Industrial Revolution. Lavishing one’s wife with jewelry was the perfect way to display a successful man’s nouveau riche standing. The 1867 discovery of diamonds in South Africa helped meet the ever-increasing demand, essentially bringing diamonds to the masses. Soon every bride-to-be wanted a diamond engagement ring.

Many solitaire styles featured a central diamond pushed up above the ring, allowing light to shine through from all directions. The Tiffany solitaire diamond mount, introduced in 1886 by Charles Louis Tiffany, was the most notable example of this style and became an instant classic that is still popular today. For the more modest budget, rings composed of smaller stones, cluster rings, and half hoops set with rows of stones were also favored. Acrostic rings composed of colored stones spelling out romantic messages, symbols such as hearts and lover’s knots, as well as the language of flowers were all steadfast Victorian engagement ring motifs. Another fashionable Victorian style was the “Toi et Moi” ring set with two larger stones representing the entwining of two hearts and two souls.

According to the 1875 Young Ladies’ Journal

Any pretty fancy ring may be worn as an engagement-ring. Pearls or diamonds are considered the proper gems. The engagement-ring is not considered after marriage to answer the purpose of a keeper. A keeper should be a chased gold ring without stones in it. It is worn on the same finger as the wedding-ring.” also “… opals, on account of their signification being “sorrow” are not fashionable for engagement rings.2

Georgian Engagement Rings

By the mid-18th century gemstones, including diamonds, twinkled out of sweetly elaborate openwork styles. Very clever hearts with coronal surmounts, pierced by arrows, surrounded by symbolic knots, and paired with colored stones of amuletic significance. A secretive cult of lovers gave rise to a fashion for jewelry with hidden messages including gimmels with letters attached spelling out sentiments such as “amour” and “forever.” Keeper rings designed as a surround of diamonds were popular as safeguards for the wedding ring. By the mid-eighteenth century, the diamond ring was the first choice of those becoming affianced.

Betrothal rings often featured rose and table-cut diamonds because the custom was for these stones to be passed down from one generation to the next. Diamonds were discovered in Brazil c.1727 thus dramatically increasing the supply thus making diamonds de rigueur for the well-dressed of the day. Those who could afford “new” larger stones were able to enjoy designs with more complicated facet patterns made possible by advances in diamond cutting technology, the early brilliant-cuts predominating. Both were set in more delicate mountings that had split shanks, and graceful openwork. King George III presented Queen Charlotte with a diamond solitaire engagement ring in 1761 demonstrating the long history of this popular style.

Antiquity & The History of Engagement Rings

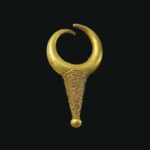

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Betrothal rings from antiquity are not a practical choice for everyday wear, but it is interesting to explore the roots of the modern engagement ring as having come from these much earlier customs and traditions. Conventions and practices with regard to betrothal rings were as varied as the countries and centuries in which they were presented. There were assorted notions as to which hand and/or which finger should bear the betrothal ring, whether to wear two rings or one and, with two, whether to wear them together or separately. The style and design of the ring including which gems, what shape, symbols, enhancements, and mechanisms were constantly changing much as they do today, sometimes due to technological innovations and sometimes as a result of changing fashions. Even the most basic question of when to present the ring, i.e. betrothal – upon asking for her hand or at the wedding or both evolved over the centuries and from region to region.

The English word engagement has its roots in the French word engager meaning to pledge. Use of the word in everyday English parlance began circa the seventeenth century and referred to battles or fighting. Engagement joined the wedding lexicon circa 1742 and was defined at that time as a betrothal or promise of marriage. Interestingly enough this was about the same time that the presentation of an engagement ring became customary among those who had the means to afford it. Prior to this time, there might be a separate betrothal and wedding ring but the styling and construction were quite different from the rings we see today.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Early betrothal rings not only symbolized love and marriage but originally represented an actual value in coin with the promise of more at the wedding. In some cases, the amount of money to be awarded was defined by law and could be presented in coin or in the form of a ring confirmed to have a value equivalent to the legally required coins. Other ring designs had functional uses and/or symbolic meaning for the future of the relationship. Rings designed as keys symbolically granting access to the household and all it contained, occasionally they were actually functional and physically allowed access to goods necessary to run a household. A seal or signet ring was more than a symbol, it granted the wearer to the authority to “sign” for goods and services using the seal.

One notable custom involves the question of which hand and even which finger a betrothal or wedding ring should be worn. This varied from culture to culture and generation to generation. The Greek Church stipulated that the right hand was to be used for betrothal and wedding rings and most European countries did the same from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries. The French favored the right hand until circa the fifteenth century and some Scandinavian countries continue that tradition today. Other cultures split the betrothal ring and wedding ring between the right and left hands.

Various fingers (and even knuckles) were designated for the special purpose of bearing this important symbol of love. Religious rituals placed the ring on the “third” finger (what we call the ring finger) because the religious presiders at marriage ceremonies would point to the fingers in order (index to ring) and say “In the name of the Father, of the Son and of the Holy Ghost,” touching each finger in turn ending on the ring finger where they then placed the ring. Jewish betrothal rings were placed on the index finger and there is artistic support to indicate this was the custom throughout seventeenth-century Europe as well. Thumb rings were popular during the reign of George I in England, and the thumb has also been the custom in India. In addition, there was a widely held erroneous belief that a vein leading directly to the heart ran through the “fourth” finger (counting from the thumb) on the left hand and that therefore the betrothal ring should rest on that finger. We know now that blood flows through all our fingers and eventually returns to the heart making them all equally connected, but the tradition continues.

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

The French had a fondness for the gimmel ring and in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the gimmel graduated from a friendship ring to a full sponsalium annulus or “ring of affiance.” The name gimmel has its root in Latin – gemellus – meaning twin. Gimmel rings began to turn up all over Europe in various forms and designs. The most popular was the twin ring with clasped hands that could be unclasped by rotating the rings on the pivot point. Puzzle rings were seen as a type of gimmel ring, though they usually had five or more intertwined rings. Similar alliance rings consisted of a gem-set ring and a signet ring, worn separately by bride and groom respectively, that could be joined together at the marriage ceremony.

During the American colonial period a tradition of presenting “keeper rings” as betrothal rings, typically consisting of a hoop of small diamonds. Once the marriage took place and the wedding band was put on the finger, the keeper ring would be put back on the finger to act as a guard ring for the simpler, but more important wedding ring. Losing one’s wedding ring was considered bad luck and most wedding rings were never removed during a lifetime of marriage, so the keeper/guard ring had a very important function and may have been the precursor of the modern engagement ring.

As you can see the history of this important and symbolic jewelry gift is long and varied. Other jewelry items rise and ebb in popularity or become obsolete, but engagement rings are here to stay. No matter the choice of style, gems and materials, the important feature of an engagement ring is the outward representation of the love it symbolizes. Choosing the ring that “speaks” to the personal tastes and lifestyle of you and your fiancé, and represents the love you share, is a magical journey. Bon Voyage!

Sources

- Church, Rachel. Rings. London: V&A Publishing, 2014.

- Collins, Kathrine. As Endless is my Love as This: A History of Marriage Rings. London: Empress, 2014.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714-1830. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collector’s Club Ltd., 2007.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Kunz, George Frederick. Rings for the Finger. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1973. (J.B. Lipincott Company, 1917).

- Levi, Karen, Editor. The Power of Love: Six Centuries of Diamond Betrothal Rings. London: Diamond Information Center 1988.

- McCarthy, James Remington. Rings Through the Ages: An Informal History. Harper & Brothers: New York, 1945.

- Sataloff, Joseph. Art Nouveau Jewelry. USA: (no publisher listed), 1984.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Rings: Jewelry of Power, Love and Loyalty, London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd., 2007.

- Scarisbrick, Diana & Henig, Martin. Finger Rings: From Ancient to Modern. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2003.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Rings: Symbols of Wealth, Power and Affection, London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd., 1993.

- Tait, Hugh. Seven Thousand Years of Jewelry. London: British Museum Press, 1986.

- Ward, Anne, Cherry, John, Gere, Charlotte & Cartlidge, Barbara. Rings Through the Ages. New York: Rizzoli, 1981.

- Zorn Karlin, Elyse. Jewelry & Metalwork in the Arts & Crafts Tradition. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. 1993.