As the austere and world-weary 1940s morphed into the fabulous and affluent 1950s, gold jewelry retained its popularity but with a twist, a tassel or a texture. Ribbons and bows, flowers and leaves so popular in the 40s, were being rendered in the new more textural style. Gone were the smooth and silky expanses of mirror finish; the satin ribbon-like gold swaths and sinuous swirls were usurped by woven, linked, twisted and textured chunky gold renderings of the same themes. The influence of Abstraction and Surrealism on the art world found it’s way into the design of everyday objects and these same curvilinear shapes began to impact the world of jewelry. Grittier, amplified and articulated three-dimensional textile motifs were employed to set off bold gemstones and make a fearless fashion statement. After the parsimonious war years, the world was ready for flamboyant displays of gems and jewelry.

The world of haute couture sought to celebrate the feminine figure with a wide array of sumptuous fabrics featuring silks, brocades, and lace. In 1947, Christian Dior introduced a new look in fashion that brought femininity back, rejecting the somber wartime silhouette. A fitted bodice and décolleté neckline atop a full skirt flowing out from a tight-fitted waistline called for a newly revised design aesthetic for the fashion’s complimentary jewels and accessories. When it came to jewelry the phrase “the more the merrier” seemed apropos.

Photo Courtesy of DeBeers.

To punctuate this elegant display of elan, diamonds set in platinum swept across the feminine décolletage and swirled on lobes newly revealed by upswept hair which was held in place by diamond clips. DeBeers Diamond Corporation ensured that the demand for diamonds would not wane with their ‘A Diamond is Forever’ campaign. By an ingenious focus on using a multitude of smaller diamonds instead of a large focal gem they were able to promote diamonds to every income level, especially the rapidly growing middle class. They cleverly awarded prizes to jewelers worldwide who encompassed beauty, design, function and most of all, diamonds, in their modern compositions.

Photo Courtesy of New York Social Diary.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

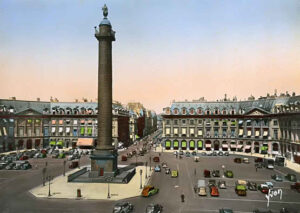

Once again, Paris was the center of Haute Joaillerie with the pulse of the jewelry world firmly beating in the Place Vendôme and on the Rue de la Paix. The major pre-war jewelry houses, Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Sterlé and others, were still the height of popularity finding a wider audience among the newly prosperous by relying heavily on their pre-war designs while innovating and integrating new looks such as Cartier’s innovations on its iconic panther brooch. American jewelers were raising their profiles with the keen use of designers like Jean Schlumberger for Tiffany. In New York Harry Winston was in his heyday, securing important diamonds, gems and pearls in dainty, flexible platinum settings. He believed gemstones were the essential element of the jewel; they alone dictated the design. His breathtaking creations were enormously successful with his wealthy clientele.

Photo Courtesy of Bonham’s.

There was a trend for matching accessories, which fueled an appetite for suites of jewelry or demi-parures rendered in either bold gemstones and gold or in diamonds and platinum. Various combinations led the trend: necklace and earrings, dress clips or brooch and earrings or bracelet with brooch or earrings and were required accessories for the new daywear fashions. Earrings for daytime were short but bold and clipped on the ear with nary a dangle. Bracelets were typically textured wide straps and featured articulated woven and twisted motifs that sometimes concealed a watch. chokers of pearls, woven gold collars and twisted torsades, often displaying an elaborate gem laden clasp, adorned the neck while brooches edged the neckline or bodice. Rings were slower to evolve from the big bold gems of the 40s, but gradually eased into a more elaborate yet genteel style.

Brooches

Naturalistic motifs exploring all forms of flora and fauna were more popular than ever and brooches exemplified the trend. Flowers solo and in bunches, enameled, bejeweled and textured in gold, carved from gemstones or rendered in platinum and diamonds, flourished on every type of jewelry, but most especially on brooches. Leaves and feathers, articulated and stationary, were carved from gem material, woven and/or textured in gold, and flowed singly and in clusters on the feminine bodice. Accompanying these bouquets and vines were their counterparts from nature, bees, bugs, nuts, and berries. Super serious and raucously ridiculous zoomorphic collections of animals posed and pranced accented by enamel and gemstones of every hue. Not to be left out, undersea life was also in vogue, seahorses, fun fish, crabs, squid, and octopi floated realistically and comically throughout the 1950s.

Earrings

While earrings from this period included both dangling pendant and button styles, the period is known for its gem-laden oversized earclips. Gold leaves, flowers, spirals clusters, and disks were daywear de rigueur. Evenings more often glimmered with diamond set clips in a multitude of shapes and designs, some suspending a single large diamond or an entire cascade of smaller diamonds. Large pearls and mabe pearls either alone or with a decorative surround were a classic touch.

Bracelets

Bangles, ropes of pearls, torsades, and gold mesh were popular styles for daywear bracelets. Mesh and wire bracelets flanked delicate watch dials, doubling wristwatch with bracelets for day and evening wear. For evening, a diamond-encrusted bracelet with a large central focal element in a floral, rayed or swirl motif, completed by a slender line of diamonds or diamond strap was a glittering 50s look. Another uniquely 50s style was the charm bracelet, serving a dual purpose as jewelry and as an opportunity for personal expression. Amassed as travel mementos, used to mark memorable occasions or collected to just be whimsical, charms were a hot ticket item. Literally, anything was fair game to become a charm dangling from a chain link or bangle bracelet: large disks with engraved dates and messages, articulated novelty items and an amazing variety of everyday items. Clustering as many charms as possible on the bracelet was the goal of most collectors, a few, however, sported a more austere bracelet with one (or a few more) emblems.

Necklaces

Chokers clinging to the base of the neck were the design of choice for day and evening, perfectly complimenting the open necklines of mid-century fashion. Necklaces came in many forms, but one of the most popular was a bib front tapering to a line of gems or links at the back. For daytime, the composition was usually dominated by yellow gold with lots of texture and colorful gemstones. For evening, diamonds in lines, bibs and with symmetrical and asymmetrical swirl elements and articulated diamond fringe and waterfalls. Rows of larger pearls and gemstone beads, some with elaborate clasps, could transcend the time of day. Multiple strands of smaller beads and pearls were usually worn with a twist as a torsade. While tiaras were once again in style, they were no longer a dedicated jewelry item, so necklaces (and sometimes brooches) did double duty as hair ornaments.

Rings

Rings remained large well into the 1950s but the lines softened to more curvilinear outlines. The Bombe ring was trendy and usually dotted or encrusted with colored gemstones. Coiled and twisted wirework superstructures supported large gemstones high atop the finger. Ballerina rings and glimmering gemstone clusters came in a plethora of various sized and shaped stones. Bypass rings were oversized and often highlighted outlandishly large gems and motifs.

Mid-Century Modern

Growing alongside the traditional jewelry design houses there was a modernist movement of Mid-Century American Studio Jewelers in the United States that took their inspiration from pre-war Europe. Salvador Dali, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau were among the artists who inspired American Studio Jewelers to create “Jewelry as Art” or “Wearable Art. Drawing their inspiration from the philosophies of Bauhaus, Dadaism, Surrealism, Isomorphism and Cubism, the modernist‘s work was characterized by abstract and non-objective form. Creations by Mid-Century American Studio Jewelers were often one-of-a-kind and totally hand fabricated.

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Raulet, Sylvie. Jewelry of the 1940s and 1950s. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1988.