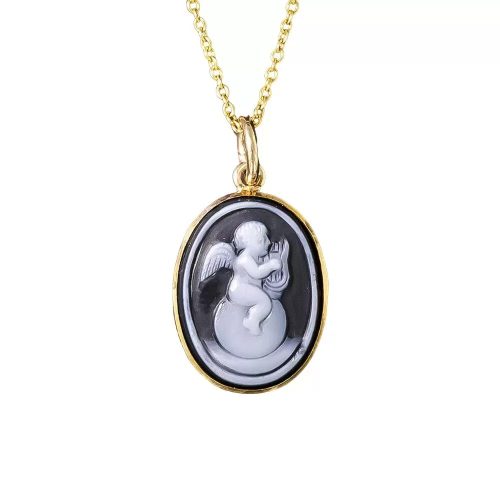

Cameos, valued since antiquity as engraved gems, were exceedingly popular during the Georgian and Victorian periods. Many different materials were used for carving cameos. For hardstone cameos, varieties of agate including onyx, sardonyx, and jasper were popular. These stones, with layers of different colors, allowed for depth and nuance in the carvings. Other non-layered gemstones such as malachite, coral and amethyst were fashioned into magnificent monochrome cameos.

Shell was another popular medium for use in cameo carving because it was light in weight and therefore didn’t limit the size of the piece. Tropical helmet shell was extensively used for its good color contrast and depth of layers. The Cassus rufus variety was white and pink, the Cassus madagascariensis had white and brown layers. The depth of the white layer in the helmut shell was sufficient to allow very high relief with lots of detail.

The methods used for carving these two types of cameos were as vastly different as the materials themselves. Hardstone was cut on a specialty lathe with steel drills and wheels. Carvings using this process took months to complete. Shell cameos could be carved by hand with a burin or engraving tool, taking only days to complete a magnificent carving. These less labor intensive therefore less expensive shell cameos were popular with tourists looking for just the right souvenir of their trip.

The myriad of cameo subjects included figures and scenes from Greek and Roman history and mythology. Renaissance art, classical sculpture, famous paintings and official portraits also provided inspiration. Religious imagery included Christ, the angel of the annunciation, PAX, and the crown of thorns. Cameos were considered “smart” jewelry because of the intellectual nature of the subject being carved. Tourists on holiday, viewing the full sized artworks, were delighted to take home a wearable miniature version as a remembrance.

(1763-1814) c.1908.

Empress Josephine is credited with initiating the fashion for cameos. Antique gems from the royal treasury were set by her jeweler, Nitot, in the Crown of Charlemagne and in bracelets for the Empress. A portrait of Josephine wearing a parure of cameo jewelry sparked a multinational trend. During the Restoration in France, the fashion died out while in England the trend stayed alive continuing to build. France once again enjoyed cameo jewelry under the rule of Louis Philippe.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

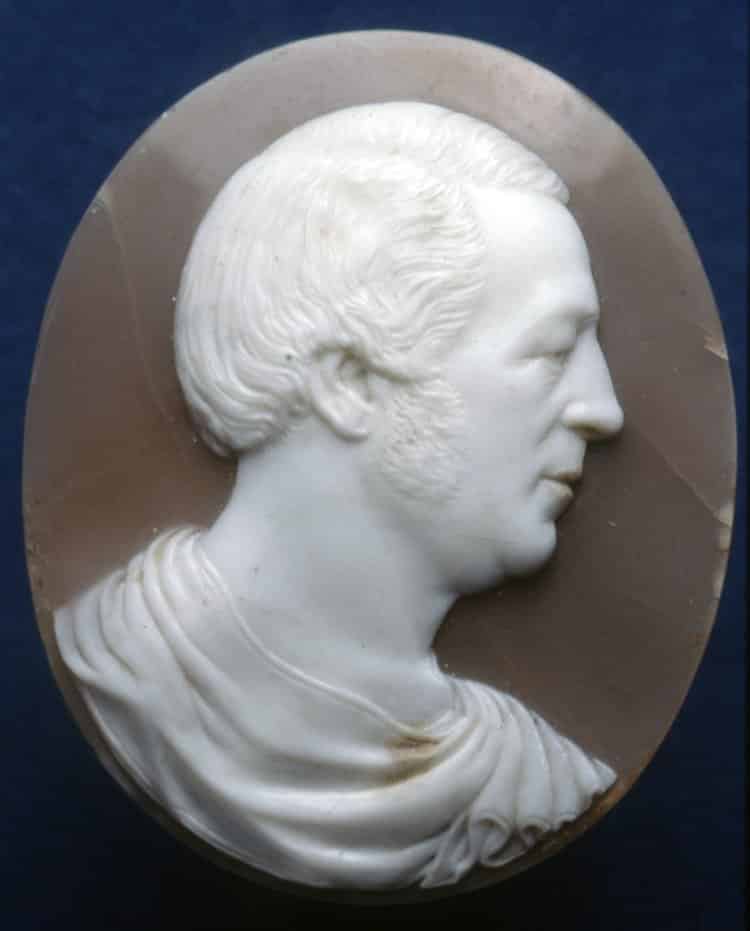

Imitations of ancient gem carvings were exceedingly popular with the Georgian and Victorian consumer. The inventory of engraved and carved gemstones of the past was more accessible to Victorian gem carvers than one might think. Catalogues of line drawings depicting famous collections were printed and sold. Plaster casts of these earlier works were circulated among collectors. John Tassie’s glassworks began production of molded replica cameos circa 1791. Nineteenth-century gem carvers had access to classical works as well as those of their contemporaries resulting in a great deal of copying and the creation of untold numbers of replicas. Carvers began to sign their cameos in the mid-eighteenth century in an effort to prevent dealers from selling their work to collectors as antiques.

A third technique, commesso, joined together layers of different materials such as hardstone, coral, and mother-of-pearl, was a French form of gem carving that resulted in a pictorial relief, not a true cameo.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Gem engraving was often the means for a struggling sculptor to make a living. Engravers from all over Europe and America congregated in Rome, the international center of cameo cutting, to produce these small artworks for the tourist trade. As a result, the sculpture and artwork of Rome both contemporary and antique were the subject of many cameos. The production of cameos representing more recent works of art helped propel the desire for cameos firmly into the nineteenth century.

The relative ability to quickly carve shell cameos permitted the artist to use live subjects. Often portrait cameos were produced after a marble bust had been made of the subject. The gem engraver would later copy the bust as a cameo. By this time photography was available to provide subject matter for cameo carvers. To distinguish carvings “from life” the artist would sometimes make that notation on the reverse of the cameo.

Cameos commemorating a marriage or other event could be produced in any quantity. Even if the live subject was available, these commemorative cameos were usually produced from a photograph preventing long tedious sittings for the subjects and the carver could create as many identical cameos as ordered. This made commemorative cameos available to a wide range of society previously unable to afford such a luxury.

Cameos were imported by the thousands into England waiting to be mounted by the many jewelers specializing in cameos. Jewelers often specialized in one type of cameo or another. Antiquities, coral, mosaic, and even different subject matter often went to a jeweler who carried only that specialty. Many unsigned shell cameos were available to be selected by a customer to be mounted to their taste.

Many options for mounting were available. Archeological styles, Etruscan revival, plain gold bezel, framed in gemstones or set in intricately created Renaissance revival enameled frames were available to the customer to complete the piece. Rings, brooches, bracelets, lockets, and pendants could all be set with cameos. Choice of subject, frame style, material and mode of wear made for an unlimited array of cameo jewelry and offered the wearer an excuse to own multiple pieces set with cameos.

Cameo Artisans

| Cameos | Artist | Signature |

|---|---|---|

© Trustees of the British Museum. | Niccolò Amastini Italian 1780-1851 | |

c.1880, Jasper. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Georges Bissinger French Fl.1860-1890 Exhibited: | None |

© Trustees of the British Museum. | Joseph Edgar Boehm Born in Vienna – Hungarian parents 1834-1890 | BOEHM |

c.early 19th Century, Sardonyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Domenico Calabresi Italian Patronized by Pope Gregory XIII | |

c.1876, Onyx. Apotheosis of Napoleon I – a large sardonyx cameo (24 x 22 cm) From the ceiling by Ingres in 1854 in the Paris Hotel de Ville. | Adolphe David French 1828-1896 Gem engraver and medallist. | None |

c.1840-50. Sardonyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Giuseppe Girometti 1779-1851 Noted gem engraver, medalist, and sculptor. He won numerous prizes for his hardstone cameos. He worked as head engraver at the papal mint. | GIROMETTI |

© Trustees of the British Museum. | Pietro Girometti 1811-1859 Son of Giuseppe. Some of his works are attributed to his father under whom he learned the art of gem carving. | GIROMETTI |

c. 1850. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Joseph Greenough American Boston MA 1848-1879 Trained as a sculptor from a family of sculptors, he is thought to have learned shell cameo carving during time he spent in Italy. | J.A. GREENOUGH – including a number, date, and place. |

c. 1790, Onyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Christian Friedrich Hecker Italian Worked in Rome after 1784 | HECKER |

c.1855, Sardonyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Paul Victor Lebas French fl. 1851-1876 | P. LEBAS |

c. 1781, Cornelian. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Nathaniel Marchant English 1739-1816 Award-winning Intaglio engraver, “Sculptor of Gems” to the Prince of Wales, 1789, “Chief Engraver” to His Majesty, 1799. Many works by Marchant were lost during an air raid in 1941. | MARCHANT |

c.1726-1775, Sard. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Johann Lorenz Natter German 1705-1763 Gem Engraver & Medallist. | NATTÉR EPOIEI |

c. 18th century, Onyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Giovanni Pichler Italian 1734-1791 Gem Engraver in Rome. | PICHLER |

c. 1816, Sardonyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Benedetto Pistrucci Italian Roman trained sculptor whose patron was George IV, made a career of gem carving in London and also worked for Royal Mint. | PISTRUCCI |

c. 1870, Shell. © Trustees of the British Museum. | James Ronca Swiss/Italian 1826- ? Working in London took over for the Saulini’s making the Royal Family Order badges. | RONCA |

c. 1850 Onyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Tommaso Saulini Italian 1793 -1864 Roman cameo carver, worked in hardstone and shell, produced cameos for the Royal Order of Victoria & Albert. Scuptor Gibson who made busts of the royal family and negotiated the carving of medals and badges between the Saulinis and the Royal Family. | T. SAULINI F. |

c. 1850, Onyx. © Trustees of the British Museum. | Luigi Saulini Italian 1819-1883 Sketched his subjects’ first (sometimes from a photo taken by a nearby photographer who worked with Saulini.) Very talented hardstone carver (trained by his father Tommasso (1784-1864) continuing the family trade) also carved less expensive shell cameos. He used sculptures/statues as inspiration. Son of Tommaso – Cameo portraitist. | L. SAULINI F. |

c. 1900, Opal (attributed) © Trustees of the British Museum. | Wilhelm Schmidt Idar, Germany 1845-1938 Studied gem carving in Paris. Working in London (changed his name to William) and carved Renaissance inspired cameos set by Brogden, Giuliano and Child & Child. He was famous for carving cameos in opal matrix. | None |

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery: Second Edition: Colchester, Essex, N.A.G. Press Ltd., 1987.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Miller, Anna M. Cameos Old & New: 2nd Edition.Woodstock VT: GemStone Press, 1998.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Jewellery in Britain: 1066-1837: Whitby Hall, Whitby, Norwich: Michael Russell Publishing Ltd., 1994.