Minoan and Mycenaean Jewelry

Crete

When describing jewelry from Greece one should start with the Minoans. Around 3000 BC signs of a new civilisation on the island Crete started to emerge. The origin of this new culture most likely lies in Asia Minor, a theory that is supported by the jewelry the Minoans produced. The forms and techniques used resemble Sumerian jewelry. Over the time frame, 3000 – 2000 BC the civilisation developed into a unique and splendid culture and its jewelry became a style of its own.

The Minoans were sea-faring traders who maintained close contact with the Egyptians, Syrians, Hittites and those living on the islands of the Greek archipelago and mainland Greece. Their trading routes may have gone as far west as the east coast of Spain. Apart from exchanging goods, the Minoans would have been bringing knowledge and techniques to wherever they went. Trading posts were established and Minoan ‘colonies’ or settlements acted as a hub for technical and cultural innovations.

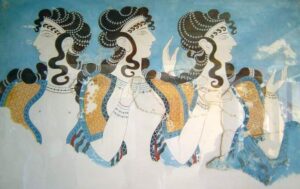

From around 2400 BC gold jewelry was produced on the island from imported gold. Graves from this era containing pendants, diadems, hair ornaments, beads and bracelets from sheet gold on top of rather sophisticated loop-in-loop chains, all with characteristic Babylonian influences, have been excavated. Some 400 years later the fine techniques of granulation and filigree were introduced. The use of bead necklaces, bracelets and hair ornaments is nicely illustrated on one of the many frescos that are preserved in one of the palaces of Knossos.

Showcase

Mycenaean

Being an offspring of the Minoan culture, the Mycenaean civilisation comes to its height at around 1450 BC when it conquers the Minoan palaces on Crete. Jewelry produced by the Mycenaeans doesn’t differ much from Minoan jewelry. Reynold Higgins, co-author of 7000 Years of Jewellery mentions that:

“Mycenean jewelry is more plentiful but less adventurous in content than the Minoan”‘

The Mycenaeans had access to larger quantities of gold and subsequently more gold jewelry was produced.

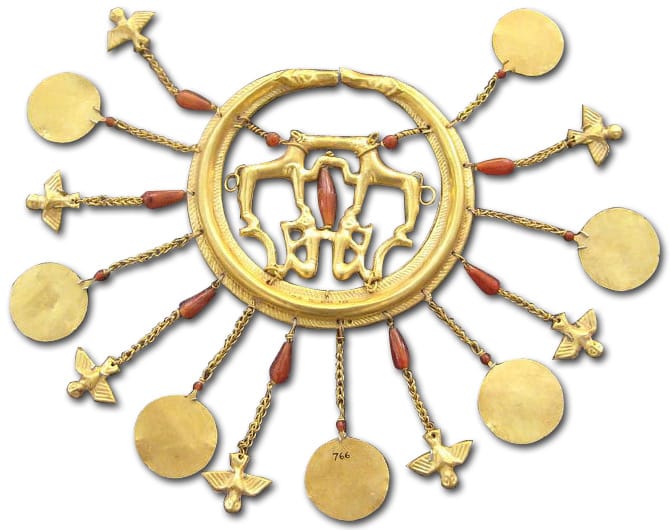

Courtesy of the Louvre.

Large-scale manufacture of beads shaped as spirals, flowers, human heads, flowers, beetles and other stylized forms was developed. Parts of the basic shapes would be stamped out of sheet gold in parts with the aid of dies. Next, the parts would be joined and the bead filled with sand. The Mycenaean craftsmen booked progress on the techniques of engraving of precious stones illustrated by complicated seals for rings, the use of simple enamels, colored stones for inlay and the art of making fine chains from gold wire.

Around 1100 BC the Mycenaean civilisation disappears suddenly. The reasons for this abrupt discontinuation are subject to suggestion, a natural disaster, disease, war, all are possibilities. Fact is we don’t really know for sure what happened. What we do know is that for 200 years hardly any jewelry is being produced in the Greek lands.

Greek Revival

There is little to no evidence that there has been a continuation of jewelry production in the Greek areas. This makes it remarkable that the jewelry produced after the 1100-900 BC period strongly resembles that of the Mycenaean and Minoan cultures. A possible explanation could be that the Phoenicians, traders from the Levant, reintroduced the styles and techniques which they had picked up from the Minoans and Mycenaeans before the Dark Ages (1100-900 BC). The Phoenicians are well known for their excellent craftsmanship around the turn of the second to the first millennium BC. Their influences came, amongst others, from the Myceneans only to return the favor and teach the Greeks of the 8th and 7th century BC what they had learned from their ancestors. The Eastern techniques and styles the Phoenicians imported make jewelry from this period a mix of old Greek tradition with new oriental accents.

Some superb 9th and 8th century BC gold work from Athens, Corinth and Crete has been excavated. Over the period that follows we see a shift of wealth: the Greek islands are producing more and more high-quality jewelry while the manufacture in Athens decreases. A shortage of gold on the Greek mainland may have been the cause. A 100-year period between 575 and 475 BC saw another decline in jewelry production, the little jewelry that has been found from this time didn’t come from the Greek mainland but from Greek colonies in Italy. After the Persian wars between 490 and 480-479 BC gold became more plentiful again.

Classical Period

During the beginning of the Classical Period (475 – 330 BC), the jewelry style was a continuation of the styles we see in the 7th century. The workmanship lost a bit of its finesse but the general idea stayed the same. Over the course of the classical era, we see some changes though. Naturalistic wreaths emerged over the 5th century BC and became popular during the 4th century BC.

Elaborate earrings featuring human figures, typical for the later Hellenistic period, start to appear around 350 BC. The old-style beads and pendants were adapted to fit into the ‘modern times’. Complicated necklaces with acorns, birds and human heads became popular. Bracelets were produced in the form of spirals or nearly closed circles with elaborate covers. Some finger rings acted as purely decorative jewelry and others were engraved as signets or featured engraved seal stones. Granulation and inlay were used rarely, filigree and enamel became more popular and we encounter the first engraved stones set in finger rings.

Showcase

Hellenistic Period

The period from 325 BC until the rise of the Roman empire in 27 BC is called the Hellenistic Period, a time when gold became plentiful again in Greece. Gold mining operations in Thrace initiated by Philip II and Alexander’s successful campaigns to the East brought bounties from Persia and provided the Hellenistic goldsmiths with the much-needed base metal. The jewelry production from the 3rd century BC remained in tradition with that of the classical period.

The conquests of Alexander the Great in Persia, Asia Minor, and Egypt changed the Greek world in a huge way. The Persian Empire got flooded with Greek colonists who ‘Hellenised’ their new neighbours. In return, the Greeks were influenced by the Egyptians and Western Asians in a greater way than ever before which can be seen in the jewelry of the 2nd century BC. Three things changed.

- New decorative motifs were introduced such as:

- The reef knot was introduced from Egypt where it had been popular as an amulet since the beginning of the 2nd millennium. Once adopted it stayed popular into Roman times.

- The crescent which started to get used as a pendant in Hellenistic jewelry. This motif came from Western Asia where it had been in use as a representation of the moon god.

- the popularity of new Greek motifs like the gods Eros and Nike.

- New jewelry forms were introduced such as:

- Hoop earrings with animal or human heads.

- Diadems with reef knot motifs which emerged around 300 BC and remained popular for about 200 years.

- New types of necklaces of complicated chains with animal head finials that were worn from shoulder to shoulder rather than around the neck or straps with pendants of buds or spearheads.

- Important technical innovations like:

- The use of stones and glass for colorful inlay, possibly the most impressive change of the Hellenistic era that has caused the polychrome jewelry so characteristic of this period.

- Beads were not threaded but linked together. This technique is typical for the 2nd and 1st century BC.

- The sophistication of the Greek glyptography; stones were drilled with the help of a bow drill or wheel, abrasives and diamond tips for fine lines. Intaglio‘s had long functioned as seals and were usually made of carnelian and sard. Cameos were introduced during this era. The favorite stone being used was Indian sardonyx which has a banded structure that was ideal to create contrast between fore- and background.

Sources

- 7000 Years of Jewellery, Various Authors, edited by Hugh Tait, British Museum Press, London, 1986.

- Ancient Jewellery: Interpreting the Past, Ogden, Jack, British Museum Press, London, 1992.

- Jewelry, from Antiquity to the Present, Phillips, Clare, Thames & Hudson, London, 1996.