© Trustees of the British Museum.

Glyptography comes from the Greek word glyptos which means to carve. In jewelry, glyptography is the art of gemstone carving and applies to both intaglios and cameos. Begun in ancient times as one of the earliest forms of communication, glyptography continues to be found today in jewelry and decorative arts.

Circa 15,000 BC, early rock carvings called petroglyphs depicted signs and symbols scratched into rock in an attempt to communicate and record events. These early scratchings were comprised of pictographs that recorded events and ideographs representing thoughts and ideas. Pictographs eventually evolved into the earliest known form of writing, cuneiform.

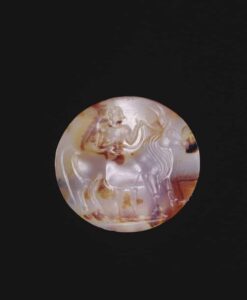

It wasn’t long before these symbols were employed in an attempt to identify and protect property and to authenticate documents. The carvings themselves were no longer made on walls but on smaller more portable surfaces such as tablets and smaller yet, seals. Seals made of wood, ivory, and stone were small in scale and contained engraved symbols that could be pressed into soft clay or wax which in turn could be affixed to nearly any surface. Items that had been “sealed” were considered safe and protected and violators were dealt with harshly. The carved stone seal itself was often worn as an amulet of good fortune and offered protection from evil to the wearer.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Cylinder seals were some of the earliest produced for this purpose. The symbols were carved into the cylinder as intaglios which were rolled over soft wax or clay imprinting it with the engraved message. Often the cylinders were pierced through the center, like a bead, so that they could be worn on a string. The Egyptians were prolific at this art but their engravings were controlled by religious dogma which limited subject matter, design, and creativity. Egyptian seals were carved in soft stones or made from faience. The use of a bow drill, combined with the introduction in c. 1375 BC of the horizontal shaft on this drill increased production dramatically.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Craftsmen from the Mycenaean civilization, c. 1600 to 1100 BC, continued to create stone seals which they cleverly incorporated into gold rings. They had figured out how to carve chalcedony and quartz but, with the decline of the Mycenaean civilization, the art of stone carving was nearly lost. The Greeks attempted to engrave stone with limited success. The carvings were crude and unimaginative. The wheel and belt drive, which allowed for skilled gem carving, were lost to the Greeks and all gem carving had to be done by hand. Circa 900 BC, The Etruscans, who not only were skilled goldsmiths but expert stone engravers, migrated to Italy. Combining their skills with those of the Greeks and with the influence of Greek mythology and style the art of stone carving was revived.

The lost technology of the cutting wheel and drill to carve stones was rediscovered by the Greeks around the 6th century BC. Seals became standardized into oval-shaped cabochons, the themes were still drawn from mythology but the renderings became more detailed and naturalistic. The use of seals became an integral part of daily life and seal makers were highly regarded.

Color became a factor in the creation of engravings and carvings. The symbolism of the color combined with the translucency of various gemstones served as important ingredients in the carving done by the Greeks in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Artisans began to sign their work. Everyone in Greece was permitted to wear a carved stone and often particular subjects were chosen as a talisman for the wearer.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

The conquests of Alexander the Great introduced a variety of new stones to the workshops of the glyptographers and Alexandria became known as the birthplace of the cameo. It was no longer necessary to carve the image into the stone as an intaglio; multi-layered sardonyx allowed the stone carver to create depth by manipulating the material so that the figures or scene could be carved in relief in the lighter colored layers and the darker color could serve as background. Sometimes multiple layers were used to provide shading and detail to a cameo. The tools necessary for this new art were already available to the artisans.

It wasn’t long before Alexander commissioned a cameo of his likeness and the cameo portrait was born. Since the classical motif was still being employed, Alexander was depicted as Zeus and thus his cameo portrait was more representative than it was a true portrait. Alexander’s exploits continued to provide glyptographers access to gold and gemstones like never before.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

During the heyday of the Roman Empire, the art of the cameo came into its own. The conquered Greeks continued to produce cameos for the Romans who used them for everything. Cameos were found as decorations on armor, as pins to secure cloaks, and collected simply for the pleasure of collecting. Popular subjects for cameos were Jupiter, Minerva, and Juno as well as Roma, who was the Roman adaptation of the goddess Athena, and a myriad of allegorical figures. The Romans’ insatiable desire for cameos kept the Greek artisans suitably occupied. Cameo cutters were known as caelatores and intaglio carvers were cavatores or signarii.

Seals were of vital importance to the Romans. Signet rings were so valued that upon the wearers’ death instructions were left as to the disposition of the signet. Symbolic and talismanic carvings were very important to the Romans. Symbols for good luck, love, magic, and worship were popular themes. The color and material chosen for the carving were as important as the subject of the carving itself.

The art of glyptography declined gradually until the fourth century AD when it disappeared along with the Roman Empire. The art of the cameo had faded but wood and ivory commemorative carvings of historical and religious events were produced in abundance. These survived to serve as an inspiration to Renaissance glyptographers. The rise of Christianity caused the old symbols to be discarded and new religious symbols such as the fish, anchor, and dove emerged.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

In the fifth century the “motto cameo” appeared on the scene. Short sentiments, often encircling a symbol, were carved into stone and given as gifts. Pagan motifs were upcycled to conform to the rigid Christian dogma. Simplistic symbols such as Egyptian palms and Greco-Roman vines and wreaths were adapted along with the more complex Hellenistic Helio or Orpheus figures which came to represent a beardless Christ figure. All the old carvings from hundreds of years before Christ were repurposed and reinterpreted to reflect the new iconography of the Christian teachings.

In the Middle East, stone carving continued. Here the subject matter was limited to inscriptions as a result of the Muslim restriction on depictions of living things. Passages from the Koran and simple prayers were the typical subject matter for these carvings.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Around the thirteenth century, the demand for cameos and intaglios was revived. The Renaissance brought with it a renewed respect for the ancient Greco-Roman arts. Better tools and technology and a new knowledge of perspective and light influenced the artisans of the Renaissance. Craftsmen copied the old cameos and created new ones with the same thematic styles. Huge collections of carved gems were amassed by wealthy and influential citizens. The classic mythological themes lent an air of sophistication to these collections as knowledge of their subject matter was considered a sign of high intelligence.

In the sixteenth century, the supply of gemstones suitable for carving became depleted. Artisans carved their new works on the back of ancient cameos. The search for suitable carving material eventually led to the use of shell. While shell was an ideal material for cameo carving, it was not at all useful in carving seals.

Seals continued to be in great demand and cameos were popular for collecting and wearing. Their production for use as commemorative items or gifts increased dramatically. The speed and ease at which shell cameos could be produced made them ideal for mass production. In the eighteenth century, gem carving schools created numerous skilled cameo carvers and the passion for collecting them thrived. Classical subjects continued to be popular themes, but souvenir cameos depicting tourist attractions and portrait cameos were increasingly available. Collected by the famous and infamous, cameos were everywhere. A noted gem carver, Roman-Vincent Jeuffroy (1749-1826), led the school instigated by Napoleon Bonapart to encourage the art of glyptography.

Early in the nineteenth century, the glyptic arts fell out of favor due to a flooding of the market with forgeries of ancient works. Without collectors fueling the market, the art declined. Cameos were still produced but those who wanted memorial or commemorative jewelry embraced the emerging photographic arts for this purpose and the cameo sunk to the lowly status of fashion jewelry. The glyptic arts never completely vanished but they have not had a significant market since the Victorian era.

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Miller, Anna M. Cameos Old & New: 2nd Edition.Woodstock VT: GemStone Press, 1998.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Jewellery in Britain: 1066-1837: Whitby Hall, Whitby, Norwich: Michael Russell Publishing Ltd., 1994.