Studying the history of this diamond is an exercise that will challenge even the most talented detective. Almost everything about this diamond’s story – from its origins to its current whereabouts – is up for debate. Those attempting to uncover the true story will find themselves sorting through a history rife with rumors, falsehoods and conflicting stories that resist verification. Add to this the fact no one has even seen this stone for over 90 years makes this diamond’s story a first-class mystery. One almost wishes this diamond were alive so that it could not only shout “Here I am,” but also set the record straight by separating the facts from fiction. Thus is the legacy of the Florentine diamond.

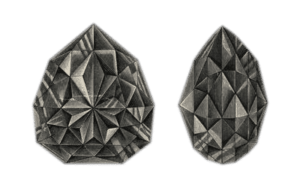

Our story begins with the famed French traveler Jean Baptiste Tavernier. It was during a trip to Italy that he reported examining an impressive diamond owned by the Great Duke of Tuscany, the future Ferdinand II (1610-1670). A member of the Medici family, the Great Duke is generally accepted as the first documented owner of the diamond. These records indicate the stone weighed 139 (old) carats with a color approximating the color of Citron. Today this would translate to a diamond weighing 137.27 metric carats with a greenish-yellowish cast. The diamond is also described as having an irregular octagonal outline with a double-rose cut that included 126 facets. Although there is no documentation to support this theory, the cutting style of this stone suggests it to be of Indian origin. Where and how the Great Duke came into possession of this diamond is unclear and undocumented. What is known is that the Medici family would maintain ownership of the diamond until the death of the last of the male Medicis.

A separate story that completely collides with the Medici ownership is a tale that the Florentine diamond was the property of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (1433-1477). Some accounts report the diamond as lost on a battlefield and found by a soldier. Believing the diamond to be glass, the soldier sold it for a florin. Since records of the time show this diamond was cut by a European – Lodewyk van Bercken – into a pyramidal shape, it is unlikely this is the same diamond that was owned by the Medici family.

In spite of the Medici family’s best efforts to keep their wealth and jewels in Florence, by 1743 the Florentine diamond had become part of the Austrian Crown Jewels. Maria Theresa of Austria was married off to Francis Stephen, Duke of Lorraine. In what was as much a business deal as a productive marriage, the union between Francis and Theresa included giving the Duchy of Lorraine to France and the Duchy of Tuscany to the Austrians. This newly formed alliance created the Hapsburg-Lorraine Dynasty. Sixteen children resulted from this marriage, including Marie Antoinette (born Maria Antonia).

Photo was c.1870 – 1900.

The Florentine diamond was set into a crown for the coronation of Francis Stephen as Emperor Francis I. The diamond remained a part of the Austrian Crown Jewels until 1918 when, at the conclusion of World War I, the Hapsburg Empire came to an end. The Austrian Imperial family sought exile in Switzerland bringing with them the crown jewels including the Florentine diamond, now set in a brooch.

It is during this time period that the Florentine diamond disappears. Whether it was due to the confusion brought on by the ending of the Great War, the dissolving of their country, their hasty exit, or the stressful journey to their newly adopted country, the Florentine diamond did not arrive with the royal family in Switzerland. Rumors swirled as to its fate. Had someone forgotten to pack it? Was it lost in transit due to careless handling? Did the royal family sell it during their journey – perhaps as a bribe to enter Switzerland? Or perhaps it was an inside job, stolen by a member of the royal family’s household.

Of the many rumors surrounding the fate of the Florentine diamond was a report that the stone was among the Austrian Crown Jewels stolen by Hitler when Germany annexed the neighboring country in the 1930s. However, for that to have happened it would have meant the royal family had left the stone behind. As stated earlier and according to documentation, they took it with them. Then there’s the additional rumor that, at the conclusion of World War II, the victorious American troops came into possession of the diamond and returned it to Vienna. However, this account was proven false by the Officials of the Treasure Room in the Museum of Art when they stated that the gem was not in their inventory. A further rumor has the diamond traveling to South America, being re-cut and reappearing in the United States.

Then there’s a parallel story involving a diamond named the Shah of Persia. Weighing in at an impressive 99.52 carats it appeared on the scene in 1923 and seemed to be a re-cut of a larger diamond. Since it was sporting what some thought to be a similar color to the missing Florentine, it was believed to be the same stone with a new cut. However the provenance of this diamond proved highly suspect and this information, combined with the fact that it was a cushion-cut stone, made it highly unlikely it could have been fashioned from the Florentine.

There is yet another account that reports a brilliant-cut diamond was offered for sale in Geneva in 1981. This account could indeed be a portion of the surviving Florentine diamond. Upon examination of this stone, there is evidence of it having been re-cut and its former owner stated that the diamond originally had an old-style cut that was now out of fashion. But again, there is not enough evidence to make a definitive identification.

The unfortunate truth is we may never know the Florentine’s fate or see it again. If only it could talk.

Sources

- Balfour, Ian. Famous Diamonds, London: Christie, Manson & Woods Ltd., 2000. Pp. 107-109.

- McCarthy, James Remington. Fire in the Earth: The Story of the Diamond: New York: Harper Brothers, 1942. Pp. 166-168.

- Florentine Diamond. Internet Stones.com, © 2006.