No longer mourn for me when I am dead,

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled.1

© UCL Bentham Project.

Mourning rings are memorial rings used to commemorate a deceased relative, a close friend, or historical figure. Early accounts of their use date from the Roman Empire, around the time of the defeat at the battle of Cannae against Hannibal (216 BC). The Carthaginian general ordered the golden rings to be taken from all slain Romans which were then sent to Carthage as evidence of the many Roman noblemen who perished during the battle (only the elite in Roman society were granted the right to wear golden rings during the reign of the Caesars). In remembrance Romans would take off their golden rings and substitute them with ones of iron in days of general mourning.2 In more recent history, mourning rings were identified from the 15th to the early 20th century with the apogee of their wearing occurring during the 18th century.

During the later years of the medieval period it became customary in some circles of society to remember a departed loved one with a plain – half – hoop ring, engraved or enameled with the initials of the deceased alongside the date of departure. In the 17th century hoops with a triangular cross-section were added to this repertoire, as well as rings with a lozenge or hexagonal bezel on which the initials of the deceased were enameled or engraved, accompanied by mottos as “memento mori” or vanitas symbols.

These rings were given at the funeral to close friends and/or family members as specified in the will of the deceased. The will of William Shakespeare, from 1616, mentions that sums of money are bequeathed to several friends to buy them golden rings. The value of those mourning rings would equal to about USD 3,000.00 in current days (26 shillings, 8 pence.)3This tradition lasted well into the 19th century. Records of the Old Bailey criminal court in London, UK show 190 incidents involving the theft of mourning rings between 1730 and 1908, often resulting in the felons being sentenced to death or transported to the penal colonies. One account mentions the shoplifting of 14 such rings from a London jeweler, showing that jewelers used to stock these rings (only part of the parcel was engraved) and have them engraved on demand.4 One of the production centers of those goods was in Birmingham, UK.5

Judge Samual Sewall:

Lost a ring

(by not attending the funeral)6

Escaped unluckily from me

A Large Gold Ring, a Little Key;

The Ring had Death engraved upon it;

The Owners Name inscribed within it;

Who finds and brings the same to me

Shall generously rewarded be.7

While mourning rings were originally handed to people belonging to the innermost circle of the deceased, in time it became a sport to collect those rings. In some circles, it was almost obligatory to bequeath large amounts of mourning rings-up to 200 rings at one 18th-century funeral were handed out in the New England region of the United States representing up to a 10th of the estate’s total value.8 Similar extravagances were also reported from the UK.9 Although this was not usually the case, people – in particular slight acquaintances – would be offended when no ring was bequeathed to them. Important figures in the community such as doctors, reverends and judges were usually included in wills and there developed a craze to collect these funeral “presents”. People of questionable taste conversed with one another in terms like “I made” or “I lost a ring”. Between 1687 and 1725, Judge Samual Sewall of Salam, MA was given 57 mourning rings which represented quite a capital on its own. No doubt his involvement in the Salam witch trials greatly contributed to that; a powerful man to whom you wished your relatives to stay on his good side.10

Styles of Mourning Rings

As with most jewelry, we can recognize some trends in mourning rings11, following the overall style of the day. Throughout the ages, a simple hoop ring remained in fashion. The materials used extended from gold and silver to pinchbeck, copper and bath metal.

- 16th century:

Plain half-rounded hoops engraved with the initials of the deceased and date of parting

- 17th century:

Hoops, half-rounded hoops or hoops with a triangular cross-section with a lozenge or hexagonal bezel. Enameled or engraved with mottos and/or vanitas symbols.

- 1660-1720:

Enameled simple -half rounded – hoops with cut-out skulls between foliage designs.

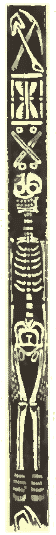

- 1734-1747:

Hoops (half rounded) completely cut out with vanitas symbols as a skeleton, hourglass, shovel, and spade and crossed bones on a ground of black or white enamel (image on the left).12

- 1730-1815:

Plain hoops with the name and date of death on a ground of black or white enamel. Also plain hoops with bezels, set with gemstones.

In the earlier part of the period; coffin-shaped bezels enclosed a skeleton under a clear crystal cover.

In the latter part; oval bezels with a golden monogram of the deceased on a ground of hair, urns, and other vanitas symbols crafted from hair.

- 1735-1775:

- From about 1735, elegant wavy hoops or scrolls, enameled and with the names of the deceased. Also, bezels set with gemstones or skeletons under a clear crystal cover.

- 1775-1800:

- Marquise-shaped bezels came into fashion.

- 19th century:

- Plain hoops were still the norm but also gypsy ring types with portraits on ivory, hair backgrounds or gemset (diamonds).

Many times the text reads “ob” or “obt“, which is an abbreviation for the Latin

word “obiit”, meaning “died”. The enamels were usually monotoned black or white; black was used for married persons, while white indicated an unmarried – usually young – person.

Hallmarks on Mourning Rings

In the UK almost all jewelry was exempt from compulsory hallmarking in the period from the early 18th century until 1973, with the exception of mourning (and wedding) rings. It was not until 1878 that the levying of duty on mourning rings was ceased.13 The reasons for the exception are not clear, but they may have to do with the fact that these rings were usually of a high carat (22 ct) and made from gold coinage (under control of the mint) and thus needed to be hallmarked for consumer protection.

Sources

- Girod, Daniel. Antieke Memorie-Sieraden. Kunst & Antiek journaal, May 1998.

- Morse Earle, Alice. Customs and Fashions in Old New England. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894.

- Chaffer, William and Markham, Christopher Alexander. Hall-marks on Gold & Silver Plate. Reeves and Turner, London, England. 1905.

- Kunz George Frederick, Rings for the Finger. J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London. 1917.

- Reddington Dawes, Ginny and Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery. Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Dalton, O.M. Catalogue of Finger Rings, British Museum. 1912.

Notes

- Opening stanza of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 71.↵

- Kunz, p.11.↵

- Purchasing power.↵

- Old Bailey ref.# t17980418-54.↵

- Girod↵

- Morse Earle p.378.↵

- 18th century advertising in the Boston Evening Post for a lost mourning ring.↵

- Morse, p.376.↵

- Dawes/Collings, p.160.↵

- Morse Earle, p.376.↵

- Dalton↵

- Also found as early as 1722; see Georgian Jewellery, p.159.↵

- Trade notes, 1881. Chaffers et all.↵