Diamonds tend to be described in such glowing terms as “beautiful,” “exquisite,” or “impressive.” The Sancy is that rare gem that carries more unorthodox labels such as “versatile” and “entertaining.” Versatile because documentation shows it being used for a variety of purposes beyond that of just a piece of jewelry – most notably as collateral for filling the coffers of numerous financially strapped royal monarchies. However, beyond such mundane uses, the Sancy has also been a part of some spicier endeavors such as being the gift from a grateful husband to his new bride following their wedding night. The diamond is entertaining due to the many rich – yet unconfirmed – tales associated with it that are the stuff of pulp fiction. This article will deal with the fact and fiction that is part of the saga of the Sancy Diamond.

The Sancy Diamond story begins in Portugal with a royal by the name of Dom António. The grandson of King Manual I, Dom António seizes the crown of Portugal upon the death of Cardinal King Henry. However, complications arise when neighboring Spain refuses to recognize his ascendancy, forcing Dom António to fight to win the throne. Needing funding for his cause, Dom António decides to leverage the impressive crown jewels of Portugal as his primary means of fundraising. Sailing off to England, Dom António’s quest for finding an English buyer proves unsuccessful. Moving on to France, Dom António finds a willing buyer in a man destined to become the diamond’s namesake, Nicolas de Harlay, Seigneur de Sancy.

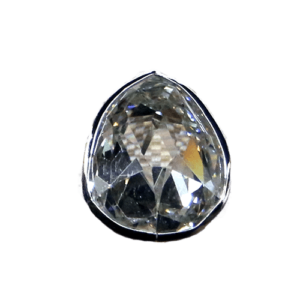

A fancier of diamonds and other fine gems, documentation tells us that Sancy purchased a 36 carat diamond later to be called Le Beau Sancy. It is commonly agreed upon that it was during this transaction that de Sancy also procured the larger almond-shaped 53.75 carat stone that would later bear his name. As for Dom António, he returns to Portugal with the money from the diamonds only to have his now well-funded army defeated by Spain, his quest for the throne of Portugal denied.

Meanwhile, back in France, legend has it that Sancy loans his newly acquired large carat diamond to his follicularly-challenged king, Henri III, who in turn uses it as an ornament on a small hat he wears constantly to conceal his bald head. The real story is Nicolas de Harlay, Seigneur de Sancy loyally serves Henri III, enjoying the rank of Colonel General and the command of Swiss troops he raised in the service of his king. However, Sancy’s real aptitude is in finance. It is a talent not lost on Henri III’s successor, Henri IV. Upon pledging his services to his new king, Henri IV wisely appoints Sancy the Minister of Finance and gives him the task of raising money for his financially strapped monarchy. The affluent Sancy solves the issue by offering his diamond as collateral to secure funding. He follows this scenario repeatedly; successfully filling the royal coffers while somehow always managing to redeem the stone.

Ironically enough, Sancy eventually finds himself in the same financial state as the monarchy he is serving. Now personally strapped for money, he is forced to part with his beloved (not to mention useful) gem collection, putting them – including the as yet unnamed 53.75 carat diamond – up for sale. Deciding his best chance for selling the diamonds lies with the English monarchy, he dispatches his brother to broker a deal with King James I. Unfortunately Sancy’s brother’s attempts to get an audience with the king prove unsuccessful and he returns to France without a sale. Like the diamond’s previous owner’s efforts to sell this diamond, the second time around again turns out to be the charm. This time it is Sancy’s cousin who, using his position as the French Ambassador to England, finally manages to meet with the King and a deal is made. Records of the Crown Jewels housed in the Tower of London in March of 1605 show the diamond being purchased by the monarchy from Sancy. It is from this point on that the stone is forever referred to by his name.

A much livelier version of this story is an unconfirmed tale that Nicolas de Sancy used a trusted servant as a messenger to dispatch the gem to England. Of course, the servant is set upon by thieves who somehow know he is transporting the valuable stone. Whether it was due to loyalty, duty, a sense of honor or just plain stupidity, the servant – when confronted by the thieves – refuses to hand over the diamond and is killed for his efforts. Yet, the thieves leave empty-handed. Rumors swirled as to the whereabouts of the diamond as Sancy calmly orders his servant’s body brought to him. An autopsy is performed on the corpse and the diamond is extracted from the dead man’s stomach. Sancy’s servant had swallowed the stone and given up his life rather than surrender it! Talk about your faithful employee! The tale’s gruesome ending lends credence to its status as an unconfirmed story.

Meanwhile, our true story continues with the Sancy diamond remaining in English royal hands for years, passing from James I to Charles I. Here, the diamond is again used as collateral. In the all too familiar story of a cash-strapped monarchy, it is Charles I’s turn to use his ownership of the stone to his advantage. In 1644 Charles sends his wife, Henrietta Maria, to do his bidding, she travels to the Netherlands, then to France offering some of England’s crown jewels – including the Sancy – in an attempt to raise money for her husband’s fledging monarchy. Eventually Henrietta “pawns” the jewels, including the Sancy and Mirror of Portugal diamonds to the Duke de Épernon who loans the crown 427,566 livres against the gems. When the English monarchy defaults on the loan, the Duke forgives the debt and keeps the stones. Eventually, the Duke de Épernon sells the Sancy and the Mirror of Portugal diamonds to Cardinal Jules Mazarin, who had already accumulated quite a collection of diamonds. Upon Mazarin’s death, his impressive collection passed into the French Crown Jewels.

King Louis XVI of France broke apart much of the jewelry in the Crown jewels and had them remade into ornaments for himself and Queen Marie Antoinette. Documentation dated 1791 shows the Sancy diamond as part of the French Crown Jewels inventory with a value of £40,000 and a weight of 53 12/16ths carats. Like many of its crown jewel contemporaries, most notably the Regent, the “French Blue” (or Hope as it is now known), the Hortensia, and many others, the Sancy diamond falls victim to the violent chaos of the French Revolution and is stolen from the Garde Meuble in 1792. Although some of the precious stones are recovered fairly quickly, many disappear forever. Upon its return, the Sancy is again pawned by the French to the Marquess of Iranda of Madrid to raise money to supply its army. From there it winds up with the widow of Charles IV of Spain who passes it to her lover who in turn tries to sell the diamond to Charles X of France.

Eventually, the diamond is sold to Russian Prince Nicholas Demidoff in 1828. Upon Nicholas’ death, the diamond passes to his son Paul. Following their wedding night in 1836, a grateful Paul presents to his wife the Sancy diamond as a “morning gift” – a Nordic custom. With Paul’s death in 1840, the stone disappears for a short time, reappearing in 1867 on display at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in the case of the famous French jeweler M.M. Bapst. Details begin to blur at this point, with one story having Bapst selling it (or a similar diamond) to the Maharajah of Patiala. Another version of the story has the diamond being purchased by Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy. Whichever road the Sancy diamond took, it does eventually wind up in the possession of the Jejeebhoy family. They retain ownership of the stone until 1889 when it is purchased by Lucien Falize, a goldsmith and Renaissance man.

Three years later, the well-traveled Sancy is purchased by William Waldorf Astor and it remains in the Astor family for 76 years. The Maharaja of Patiala also claimed ownership of the Sancy, but his diamond weighs 60.40 carats thus cannot be the Sancy. The Sancy returns to France in 1978 when it is sold for a price reported as $1,000,000 to the Banque de France and Musée du Louvre. A description, at the time, by the Gemological Institute of America states:

The diamond which is in the possession of Lord Astor weighs 51 ¾ (old) carats and has dimensions identical with models generally accepted as authentic. The diamond owned by the Indian potentate weights 60.40 carats and, although pear-shaped, actual measurements do not correspond to the accepted ones.1

In 1976 The Sancy was examined by E. A Jobbins, formerly of the Institute of Geological Sciences and he stated the following:

The ‘Sancy’ diamond is pear-shaped and approximates to a double rose cut, with mostly triangular facets but with a central pentagonal facet on each side, the latter facets roughly parallel to each other. There are slight scratches on one of the pentagonal facets. The maximum dimensions of the stone are 25.7 mm long, 20.06 mm wide and 14.3 mm deep. The weight is 11.046 grams or 55.23 metric carats, and the specific gravity (determined in toluene) is 3.519.The stone is reasonably clean, apart from a small flaw near the surface (repeated by reflection in the facets). Comparison stones were not available to us and we were, therefore, unable to colour-grade the stone, but the general appearance suggests a good colour. The stone is lively and the fire (dispersion) is well displayed…

The fluorescences of the stone by ultraviolet light are extremely interesting. By short-wave (235.77 mm) UV light, the stone fluoresces a deep yellow, but we saw no phosphorescence on cutting off the radiation. By contrast, under long-wave (365 mm) radiation, the stone fluoresces a pale salmon pink, with a very noticeable greenish-yellow phosphorescence. This behaviour is not common and, in itself, would serve as a good identification test for the stone. We were unable to detect any absorption spectrum when white light was passed through the stone.

Contact immersion photographs (by exposing photographic paper upon which the stone rests in water to short UV light) reveal that the stone is transparent to this radiation (235.7 mm) and would appear, therefore, to be a Type II diamond, as are many other large diamonds.2

The Sancy remains on display today at the Gallerie d’ Apollon in the Musée du Louvre along with other former Crown Jewels of France.

Sources

- Balfour, Ian. Famous Diamonds, Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd., 2009. Pp. 244-250.

- Copeland, Lawrence L. Diamonds… Notable and Unique, United States: Gemological Institute of America, 1974. Pp. 106-109.

- Khalidi, Omar. Romance of the Golconda Diamonds, Middletown New Jersey: Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., 1999. Pp. 71.

- McCarthy, James Remington. Fire in the Earth: The Story of the Diamond. Harper Brothers, New York 1942. Pp. 138-141.

- Streeter, Edwin W. The Great Diamonds of the World: Their History and Romance London: George Bell and Sons, 1882. Pp. 259-268.