And there is another substance, the work of man, not nature, but none the worse for that, at any rate from the point of rarity, for its creator is dead and it can never be made again as his secret died with him. I refer to the vitreous substance called purpurine.

The material has much the nature of obsidian, is of that wonderful red colour named by the French ‘sang de boeuf’, and is very heavy, having gold in its composition.1

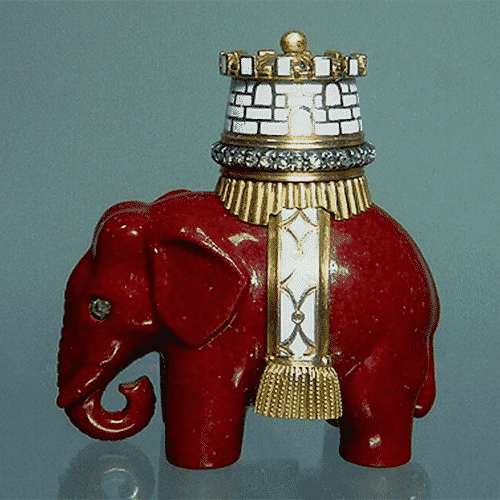

The inventory at Cartier also makes mention of the use of purpurin. As the result of what Hans Nadelhoffer referred to as “…mania for all things Russian aroused by the Ballets Russes…”2 Cartier visited Russia for the purpose of establishing a relationship with the workshops and lapidaries creating carved gemstone animals and enameled objets de vertu and other decorative “Russian style” bibelots. One such supplier was Ovchinnikov, a rival of Fabergé, who furnished Cartier with various objects including a purpurine toad. Cartier also ordered objets de vertu in purpurin from Karl Woerffel, a Fabergé supplier. With regard to the pricing of these miniature works of art, Nadelhoffer reports:

Size, type of engraving and stone quality were the decisive factors, though purpurine was treated as substantially more expensive than the different types of natural stone.3

It is believed that the earliest manifestations of this unusual glass were red glass beads from India c. 3rd millennium BCE. Red glass beads from Sri Lanka, c.1st millennium BCE, are also thought to be an early version of what would become purpurin. During the Renaissance era, Pope Gregory XIII hired Venetian glass masters to teach at the Vatican Mosaic Studio and their work and research resulted in a rediscovery of a workable formula to produce what they called ‘porporino.’

C.1700 A substance known as ‘haematinon’ from a palace on Capri, that had belonged to Emperor Tiberius, was analyzed and copper was correctly identified as the substance causing the rich red color. The source of the copper was, however, misidentified as coming from a glass slag resulting from the smelting process. A recipe for a true glass purpurin was produced in 1844 by Schubarth. Alkali-lead glass with copper oxide and magnetite infused with small amounts of magnesium oxide and carbon, cooled slowly, appeared to be a match for the Pompeian “blood glass.”

Tsar Nicholas I requested that Roman mosaicist Michelangelo Barberi come to St. Petersburg to establish a mosaic shop. Brothers Giustiniano and Leopolde Bonafede, Venetian glass masters, arrived in Russia to run the Russian Imperial Glassworks. Leopold’s potash lead crystal formula for purpurin was used to produce beautiful examples of the substance. In 1867 at the Paris Exposition Universelle there were five entries featuring the glass. Further studies by the Fabergé workshop produced a soda lead glass that had more similarities to the ancient “haematinon” than the previous recipe used at the Imperial Glassworks. The Fabergé formula was then used in all further works by the firm.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 put an end to the Fabergé workshops and the recipe was lost. It seems that none of the jewelers using this unique material documented their work and purpurin has been relegated to a historical footnote.

Alternate Spelling: Purpurine

Sources

- Bainbridge, Henry Charles. Peter Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court: London, Spring Books, 1972.

- Engle, Paul. “Conciatore – The Life and Times of 17th Century Glass Maker Antonio Neri.” www.conciatore.org, 2/08/2016, https://www.conciatore.org/2016/07/faberge-and-purpurine.html. Accessed 6/11/19.

- Nadelhoffer, Hans. Cartier: Jewelers Extraordinary: New York, New York, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1984.