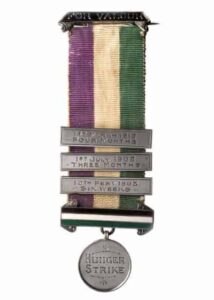

Photo Courtesy of Museum of London.

Is the jewelry often labeled “Suffragist (Suffragette) Jewelry” simply indicative of the fashion of the period or was it symbolic of a cause women (and some men) fought for passionately? Certainly, a case can be made for both points of view. A variety of mass-produced wearable emblems emblazoned with the message of the Suffragist Movement as well as individually produced pins memorializing keystones of the cause were proudly worn by its supporters. At the same time, fine jewelry bearing the colors of one of the most active groups (Women’s Social and Political Union – WSPU) was extremely popular, was this coincidence or subliminal support for the suffragists?

Photo Courtesy of Museum of London.

Undeniably the brooch designed by Emmeline Pankhurst’s (founder of the WSPU) daughter Sylvia is an excellent example of the Suffragist genre. Her design encompasses the portcullis symbol of the House of Commons, a convict symbol and hanging chains together symbolizing the suffragists who had been incarcerated at Holloway prison. These brooches were handmade, relatively rare and look nothing like the Art Nouveau, Edwardian and Belle Epoque fine jewelry labeled with the Suffragist moniker. The collection, housed in the Museum of London, includes these tribute brooches along with more mass-produced badges, sashes, scarves and other accessories that were worn as an external sign that one stood for women’s right to vote.

There are advertisements in various suffrage newspapers from both commercial and arts and crafts sources promoting suffrage jewelry, much of which consisted of individually made-up items as opposed to mass-produced commercial pieces. The problem is that if such pieces were not advertised or somehow identified through other means, there is no way today to link them up directly with the suffrage cause.1

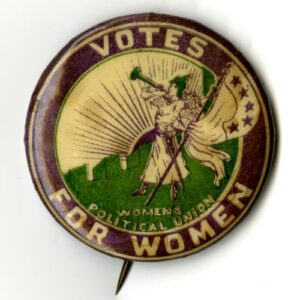

Photo Courtesy of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian.

While some form of political lapel button had been available in the United States since the times of Washington’s Presidency, in 1896 newly perfected celluloid buttons became feasible, allowing for a more colorful, yet still inexpensive, medium for these political mainstays. It was the suffragists who expanded the use of this format beyond simple candidate promotion to a wider arena – bolstering their cause. These buttons were not just simple souvenirs, but a valuable promotional item sold everywhere suffragists could be found. Millions of them were distributed and worn proudly throughout this long campaign for women’s voting rights.2

Many of these items were sold to raise capital for the cause. There were also instances where, rather than buying jewelry and badges, women donated their jewelry and precious metal household items to the cause. Depending on which would bring greater value, they were either melted (to be sold for scrap) or sold “as is” on the secondary market.

Beginning in 1908 the WSPU emblazoned themselves with green, white and violet as their emblematic colors. Bedecking oneself in the banners and badges of the movement was essential to propelling the crusade forward and was encouraged at rallies and marches. Special medals were awarded to women who were jailed for their participation and these were displayed proudly dangling from green, white and violet ribbons, some with additional bars added for each action in which they participated. Which came first… the colors or the acronym?

Purple is the royal colour. It stands for the royal blood that flows in the veins of every suffragette, the instinct of freedom and dignity… white stands for purity in private and public life… green is the colour of hope. – Mrs. Pethick Lawrence WSPU treasurer3

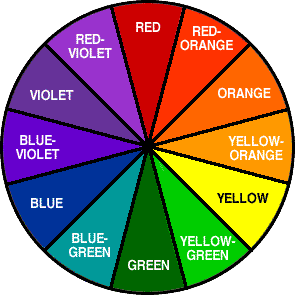

Photo Courtesy of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian.

Reaching back a century when Acrostic Jewelry was popular, it bears pondering whether the colors were chosen to have deeper (but not necessarily secret) meaning; Green (give), White (women), and Violet (votes). Since the suffragists were not being secretive with regard to the emblems and badges they wore, in fact, just the opposite was true, it doesn’t seem likely that they would wear jewelry that only covertly bore out their message. Nonetheless, these colors proved to be a very popular combination in fine jewelry of the period.

Therefore, as Goring notes, “it is important to recognize that not all jewellery in purple, white and green was intended for the suffragettes.”4 This is not to say that such generic pieces were not incorporated into a suffrage context, for women, who had been exhorted by the WSPU to “wear the colours,” may very well have purchased such items because of the coincidental color combination and not because they had been expressly manufactured for the movement.5

Jewelers wishing to jump on the bandwagon of the latest fashion trend would have undoubtedly picked up on the popularity of the WSPU color scheme as well as the innate love of the purple and green color arrangement and produced items that would practically guarantee a sale. One well-documented example is the renowned jewelry firm of Mappin & Webb who advertised suffragette jewelry in their 1909 Christmas Catalogue. And, according to Ivor Hughs:

In 1909, leading suffragists Emmeline Pankhurst and Louise Eates were both presented with specially commissioned pieces in purple, white and green.6

To provide further historical context for the use of the WSPU colors it is important to note that the latter half of the nineteenth century saw the discovery of demantoid garnet in the Ural Mountains of Russia. Its beautiful bright green color inspired a ‘demantoid fever’ that raged through Europe invigorating the Edwardian, Belle Epoque, and Art Nouveau design aesthetics. Another popular green gem of the period was peridot, which was said to be the favorite gemstone of King Edward VII, and was therefore incorporated in much of the jewelry produced in Great Britain from the mid-1800s until the onset of war.

Red-purple (violet) and yellow-green appear directly opposite each other on the color wheel making them complementary colors. The opposition of these colors creates what is referred to as maximum contrast and maximum stability. Color theory would account for the popularity of mating peridot or demantoid with a purple gem – amethyst (or rhodolite garnet). The color combination is striking to the eye and the coupling was inevitable. Add pearls or diamonds or white enamel to this combination and you have the colors of the WSPU. Jewelry in this color combination was created long before the WSPU and is still popular today. Labeling EVERY Art Nouveau, Edwardian, or Belle Epoque jewelry item in this color palette Suffragist jewelry is undoubtedly incorrect and any piece outside the years 1908 (WSPU declaring their colors) to 1914 (onset of war in Europe) absolutely incorrect.

All the buttons, badges, ribbons, stickpins, hat pins and handmade commemorative brooches and pendants that symbolized the Suffragist movement should certainly be considered “Suffragist Jewelry.” They were worn with honor and pride, displaying their message to all who saw them. Certainly, some fine jewelry of that era also qualifies, whether created to be “Suffragist Jewelry” or just purchased with the intent to be worn as such. Unfortunately, it is probably impossible to definitively declare which specific items deserve the honorable title.

Sources

- Florey, Kenneth. Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013.

- Goring, Elizabeth S. “Suffragette Jewellery in Britain,” Omnium Gatherum: A Collection of Papers – The Decorative Arts Society 1850-Present Journal 26, 2002: 85.

- Hughes, Ivor. Suffragette Memorabilia: Separating the Fact from the Fiction. New England Antiques Journal. October 8, 2015. Accessed August 15, 2016. (http://www.antique-collecting.co.uk/suffragette-memorabilia-separating-the-fact-from-the-fiction/)