Synthetic Corundum Timeline

| Year | Image | Info |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 |  | |

| 1801 |  | |

| 1817 | Guy-Lussac Found that Heating Ammonium Alum Would Obtain Pure Aluminum Oxide. Synthesizing Corundum Was On Its Way! | |

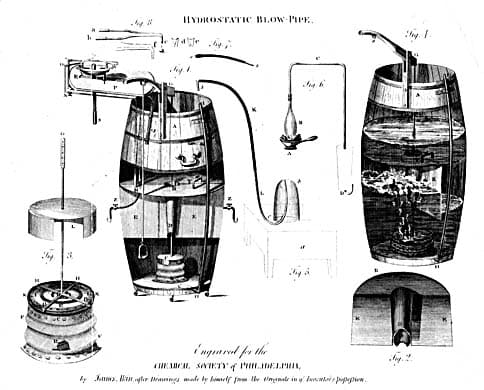

| 1819 | E.D. Clarke Publishes Details of His Experiment with a Gas Blowpipe: “ ...two rubies were placed upon charcoal and exposed to the flame of the gas blowpipe... after suffering it to become cold... the two rubies were melted into one bead".1 |

|

| 1837 | A Series of Experiments Began with Gauding and Later by Fremy. No Success as they did not have the Technology to Maintain Consistent Temperatures Needed: 2050°C. Gauding Gave up his Attempts in 1870. | |

| 1873 | The young Auguste Verneuil applies for the position of lab assistant under Fremy at the Paris Museum of Natural History. | |

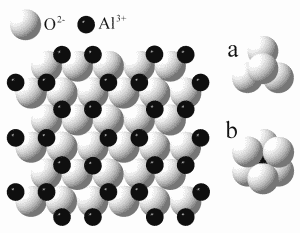

| 1876 | Verneuil became Fremy's lab assistant. At a certain point Fremy found out that using a flux of potassium hydroxide and barium fluoride made it possible to dissolve the raw ingredients at 1500°C. Gradual cooling would then cause the ingredients to crystallize. In this way Fremy created small rhombohedral crystals up to 0,3 ctIt could be argued that since experiments were conducted with several flux agents like potassium hydroxide and barium fluoride,the final product, although described as rhombohedral ruby crystal, was actually red, violet, and bluish in color.2 Ruby synthesis was understood and repeatable. The Al+3 would simply be replaced by trace amounts of Cr+3 and a ruby would result every time. Further experiments produced xls of several tones of "bug juice", which could technically be termed sapphire, even though they were not a fine blue color. The problem: Creation of various colors (aside from red) were not repeatable as the chemistry of the specific chromophore, needed to obtain colors other than red, was not understood at that time. | |

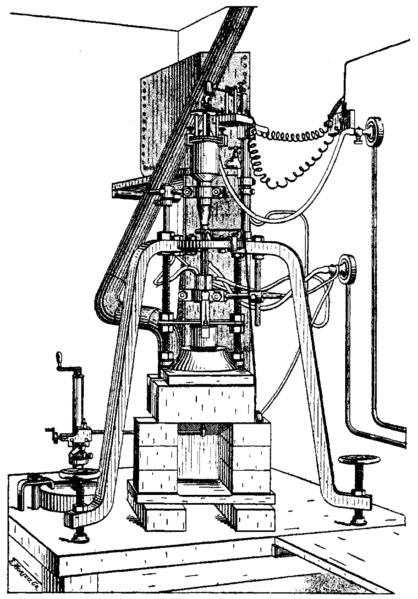

| 1886 | Synthetic Rubies, Later to be Called Geneva rubies were Shown to P.M.E. Jannettaz, a Gem Expert at the Paris Museum where Verneuil and Fremy Worked. Spherical Bubbles were Observed and After Some Research it was Concluded that the Stones weren't Natural. Verneuil was Asked to Replicate the Process and he Managed to Fuse Some Powdered Alumina Containing a Small Amount of Chromium with the Aid of a Oxygen-Hydrogen Torch. Tiny Specimens were the Result. This Event and Verneuil's Realisation that it was Possible to Produce Synthetic Corundum Through Fusing the Raw Ingredients Changed the way Verneuil was Thinking. Over the Next Years Verneuil must have Developed his Flame Fusion Method of Synthesizing Corundum. | |

| 1891 | Verneuil Deposits a Sealed Envelope Containing the Major Details of his Method. Larger Crystals were Already Produced but Verneuil hadn't Figured Out Yet How to Tackle the Tension in the Boules that Caused Cracking. Fremy Publishes a Summary of his Research and Illustrations of his Flux Rubies. | |

| 1892 | Verneuil Drops Off a Second Sealed Envelope that Contains Writings on How to Prevent and Solve the Tension Problem. | |

| 1894 | Fremy Dies. | |

| 1900 | Verneuil's Assistant Displays Several New Synthetic Ruby Crystals at the Paris World's Fair. | |

| 1902 | Verneuil Officially Announces that he Succeeded in the Manufacture of Scientific Rubies that are Equal to Genuine Ones and Large Enough to be Used in Jewelry. | |

| 1904 |  | Verneuil Publishes his Paper: Reproduction Artificielle du Rubis par Fusion. Making it Possible for Anyone with Chemical and Mechanical Know-How to Reproduce his Rubies. |

| 1907 | Worldwide Annual Production of Verneuil Rubies Reaches 5 Million Carats. | |

| 1909 | Paris Firm of Abraham A. Heller, Supplier and Manufacturer of Imitation Stones (Doublets, Imitation Pearls, and the New Synthetic Ruby) Wanted to Add Synthetic Blue Sapphire to their Bag of Tricks. They Hired Verneuil to Head their Lab, as they were Quite Confident he Would Be Able to Sort Out the Chemistry. Verneuil Began Testing Sapphires and Found the Blue Ones Consistently Contained Iron and Titanium. He Found that the Addition of Iron and Titanium in Place of Chromium Would Reliably Produce the Desired Blue Result. (In This Case: 2 Al+3 Atoms would be Replaced by One Each Ti+4 and Fe+2) | |

| 3/28/1911 and 9/26/1911 | Two US Patents were Awarded to Verneuil, and his Employer, the Heller Company, Described as "Closely Resembling Natural Sapphires as Possible" and "Having Beneath its Surface Bubble-Like Spots Bounded with Rounded Walls." | |

| 1918 | J. Czochralski Developes the Basic Apparatus Necessary toProduce the So-Called Pulled Crystals. | |

| 1958 | Experiments with the Growth of Synthetic Rubies by the Hydrothermal Method are Conducted at Bell Labs | |

| 1959 | Carroll Chatham Introduces his Flux Melt 'Cultured Rubies' After Years of Experimenting. | |

| 1968 |  Photo by Morion Company. | It was not Until 1968 that the Actual Mechanism Behind the Color of Blue Sapphire was Explained as Intervalent Charge Transfer, but the Precise Chemistry of BLUE Sapphire is Still a Matter of Some Debate Within the Mineralogical Community. It was in this Yar as Well that the First Kashan Synthetics Came out of Truehart Brown's Laboratory. |

| 1980 | Knischka Flux-Grown Rubies are Introduced. | |

| 1983 | Ramaura Flux Rubies are First Produced. | |

| 1984 | Ken Scarratt Reports on 'Float Zone' Synthetic Corundum Being Produced by Seiko. | |

| 1993 | Douros Synthetic Flux Rubies are Introduced to the World. | |

| Present |  | Numerous Corporations Produce Verneuil Synthetic Sapphires and Spinels. |

Further Resources

Gems & Gemology: The Quarterly Journal of The Gemological Institute of America.

Synthetic Corundum:

- Fall 1939, Lined Foil Back on Corundum Produces Asterism, p. 36, 1p.

- Summer 1943, U.S. Develops Synthetic Corundum Industry, p. 88, 4pp.

- Spring 1946, Synthetic Ruby and Sapphire, by Gübelin, p. 399, 4pp.

- Fall 1947, The New “Linde Stars,” Ruby and Sapphire, p. 452, 5pp. (See also Winter 1947, p. 503, 1p.)

- Spring 1951, Repeated Twinning Lines Seen in Synthetic Corundum, p. 25, 1p.

- Fall 1952, Oriented Lines in Synthetic Corundum, by W. Plato, p. 223, 2pp.

- Summer 1957, Synthetic White Colorless Corundum as Diamond Substitute, p. 57, 2pp.

- Summer 1960, Synthetic Colorless Sapphire as a Diamond Substitute, p. 59, 2pp.

- Winter 1960, A Triplet to Produce a Star Corundum, p. 119, 2pp.

- Summer 1961, More on Star Sapphire Doublets, p. 180, 2pp.

- Winter 1961, Synthetic Alexandrite-Like Sapphire, p. 249, 1p.

- Spring 1962, Sintered Synthetic Corundum, p. 278, 1p.

- Summer 1964, Polysynthetic Twinning in Synthetic Corundum, by Eppler, p. 169, 7pp.

- Fall 1965, Synthetic Star Corundum between 1947 and 1952, p. 331, 2pp.

- Summer 1967, Sintered Synthetic Corundum and its spectrum, p. 180, 2pp.

- Fall 1967, Flux-Grown Synthetic Corundum, p. 206, 3pp.

- Summer 1968, Identifying Yellow Synthetic Sapphire, p. 311, 2pp.

- Spring 1970, Hydrothermal Pink Sapphire, p. 156, 2pp.

- Winter 1970, Wisps in Synthetic Alexandrite-Like Corundum, p. 249, 2pp.

- Spring 1971, Star Doublets (Corundum Lined to Produce Star), p. 280, 2pp.

- Winter 1971, Doublets of Natural and Synthetic Corundum, p. 374, 2pp.

- Spring 1972, More on Doublets of Natural and Synthetic Corundum, p. 12, 2pp.

- Summer 1972, A New Synthetic (Pink) Corundum with Angular Parallel Inclusions, but Has Bubbles, p. 39, 2pp.

- Summer 1974, Synthetic Dark-Green and Yellow Corundum, p. 299, 2pp.

- Summer 1974, A New Synthetic White Star Corundum, p. 310, 3pp.

- Fall 1974, Strong Concentric Growth Lines on the Back of a Synthetic Star Corundum, p. 347, 1p.

- Summer 1975, A new Synthetic Pink Sapphire, p. 46, 2pp.