Andrew Grima, AKA: The Father of Modern Jewellery, was at the cutting edge of the British design revolution that swept the world in the 1960s. His own best promoter, Grima remained at the forefront of modern jewelry design for decades. He is best known for an aesthetic inspired by the elements of the natural world, executed in textured gold, featuring large colored stones. Gemstones for his work were selected for their color and shape rather than their intrinsic value, and diamonds were used sparingly, usually as accent stones. By featuring audacious colored gems he emboldened his textural designs making them stand out from the crowd.

Trained in technical drawing, Grima landed a position with a civil engineering firm at the tender age of 16. In 1940 (at 19) he joined the British Army and served in the Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. After his stint in the Army, he married Helene Haller and settled down to raise a family. Not finding engineering or technical drafting employment, he went to work for Helene’s father doing administrative tasks for his jewelry firm, Haller Jewellery Company. Compromising with his wife on a temporary trial period with the firm, he soon grew bored with the repetitive drudgery. Giving design work a shot, Grima discovered that all his skills and artistic abilities were a perfect blend for a jewelry designer. Consequently, the firm, benefitting from having an in-house designer, capitalized on it to consolidate and become completely self-reliant in design and manufacturing. Grima said of his developing style:

I set to work immediately, experimenting with all the techniques available at the time to make gold look like a material which nature might have produced. Eventually this became the hallmark of my pieces. 1

At this time, the company’s production consisted of small platinum and gold pieces set with diamonds in a classic style, mostly for export. The fortuitous visit by a pair of Brazilian stone dealers with their extensive and varied collection of aquamarines, citrines, tourmalines, and amethysts struck a chord with Grima. He managed to convince his father-in-law to purchase the entire lot. This acquisition provided Grima with the inspiration and materials needed to experiment with a style that would lift the firm from its conventional design aesthetic and develop Grima’s signature look.

Following the death of his father-in-law in 1951, Grima took a controlling interest in the company, becoming its Managing Director. He spent the next ten years attempting to grow the business in the less-than-desirable post-war London environment. By the late 1950s, Grima was pushing the firm’s output to a more modernist, sculptural style. To aid in this stylistic transition, he added Albert Hayden from Cartier and Geoffrey Turk from the Central School of Arts and Crafts, along with a few others to the team. The overall focus of the firm shifted to selling in London along with exporting to Europe. The 1957 opening of a substantially different and more modern shop in London by Michael Gosschalk gave Grima an outlet for his new designs. This arrangement continued until 1962. He also established a relationship with Hooper Bolton, another London jewelry outlet.

Another break came for Grima in the form of a De Beers competition for British exhibitors at the International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961 held at the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths (WCoG) in London. The competition was open to all members of the trade, had no jurors from the jewelry trades, and provided a £10,000 prize.

The criteria set out for the competition were that designs should be ‘both experimental and beautiful, frankly belonging to 1961, which would not have been made at any other time; as uninhibited as modern sculpture, or fashion, individual, imaginative and smart’.2

H.J. Company cast the wax models for several of the winning entries and set up an exhibition of a working goldsmith for attendees to witness jewelry making first-hand. Grima himself submitted six original designs to the competition, later admitting to Graham Hughes (Art Director, WCoG) that this competition was the catalyst that convinced him to hone in on designing only modern jewelry.

For myself, the exhibition marked the turning point in my career as designer and manufacturer… it set my mind searching for new shapes and forms.3

Britain was finally shedding the last of the post-war privations, and discretionary income was poised to pounce on something new. The Exhibition put these “modern” jewelers into the spotlight alongside other members of the arts ready to blast their way onto the scene. Grima was a leader in this movement and exerted his influence in the modern jewelry milieu for twenty more years.

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths and Grima had a long working relationship that benefited both parties. He organized events for the WCoG exhibitions, always arrived on time, and created special, stylish exhibits, charming exhibitors and attendees alike. Grima thanked the WCoG for their support with the presentation of a bust of The Queen (still on exhibit at Goldsmith’s Hall) and they acquired a collection of 28 of Grima’s jewels for their permanent collection.

De Beers also featured prominently in Grima’s success. In 1962, they commissioned a brooch from him to be used as a prize in a competition promoted by Woman magazine. In addition, he won three De Beers Diamonds International Awards in 1964. Five of the winning 1965 designs (out of a possible twenty-eight) were made in the H. J. Company workshop, four were Grima designs. During the period from 1964-1968, he won a whopping eleven De Beers Diamonds International Awards, a record in good standing. In 1972, his winning design for a diamond trophy for the King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes at Ascot was presented to the winner by the Queen. The Oppenheimer family (De Beers’ controlling family) commissioned pieces from Grima that featured important colored diamonds supplied from their mines, an unusual gemstone to be featured in a Grima design.

Further accolades came from the Queen’s Award to Industry and the Duke of Edinburgh’s Prize for Elegant Design. The Duke’s award prompted a citation from the judge:

The award recognises the emergence of a new school of creative design in Britain’s jewellery industry. 4

On Display at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

Grima’s initial introduction into the Buckingham Palace set came through Princess Margaret’s husband, Lord Snowdon. It was Snowdon’s position that British jewelry design was unadventurous. In a speech to the Council of Industrial Design, he called out the industry, and Grima took notice. Writing to Snowdon and cajoling him into touring his workshop, the Duke was suitably impressed and a friendship between the men was formed. Patronage from the Royal Household followed. In 1970 Andrew Grima Limited was granted the Royal Warrant permitting him to display the Royal Arms and the words “By Appointment to HM the Queen” on his stationary and premises. Switching her Royal offerings from sets of china to jewelry, the Queen was able to lighten her travel burdens. Consulting with Grima personally to communicate the design she had in mind, the Queen was very involved in the decision-making and design consideration for the jewelry she commissioned. These jewels were often Presentation Pieces that ended up in the collections of such luminaries as Margaret Trudeau, Betty Ford, Madame Pompidou, and others.

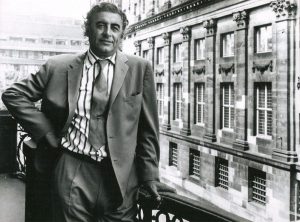

Photo Courtesy of Bonhams.

Grima struggled to keep his jewelry in the forefront of conventional retail outlets. Eventually, he opened his own shop on Jermyn Street in a building that he transformed into a temple of Brutalist modernity, becoming the hub of his empire. He expanded to open shops and develop alliances in Sydney, New York, Zurich, and Tokyo. Not to be limited in his scope, he entered into brand collaborations with Dunhill, Omega, and Pulsar to create Grima stylings for established brands. Collections entitled Opal and Pearl, Rock Revival, Supershells, Sticks and Stones, and A Tale of Tahiti went on world tours promoting his brand.

Grima relentlessly pushed his expansion despite the international financial downturns of the 1970s, which eventually led to his downfall. Taking on an investor in 1984 proved to be disastrous. Promising financial support but being unable to deliver forced Grima to close his iconic Jermyn St. hub and lose his Royal Warrant. He moved to Switzerland, specifically the shores of Lake Lugano, and opened a small shop, hoping to begin again. Living and working in self-imposed exile, Grima succeeded in perpetuating his brand with the help of his wife, Jojo, and later his daughter, Francesca.

Relocating once again, this time to Gstaad, met with success. The Cinemusic Festival requested that he design a trophy each year to present to the winning film composer. Styled with a large gemstone crystal center and a film reel surround, these behemoth awards were magnificent.

Following a 1991 retrospective, business picked up again with the London set and Andrew and Jojo divided their time between London and Gstaad until his death in 2007.

According the the Grima website:

Since Andrew’s death in 2007, his wife Jojo and daughter Francesca continue the tradition of creating highly original handmade jewellery. A limited collection of 20 to 30 pieces is created each year as only a handful of goldsmiths, most of whom have been employed by Grima for over 40 years, possess the skills required to make these unique pieces. Jojo and Francesca also accept requests for bespoke designs and offer a large selection of vintage pieces. The Grima collections can be viewed by appointment in London.5

Maker's Marks & Timeline

Grima

| Country | |

|---|---|

| City | London |

| Era | (1921 – 2007) e.1966 |

Andrew Grima (1921-2007)

- 1946: Self-taught, working at his father-in-law’s business H.J. Company, takes over the company in 1952,

- 1966: Duke of Edinburgh’s Prize for Elegant Design, Queen’s Award to Industry.

- De Beers Diamond International Award (won 11 times)

- 1969: Created a watch line for Omega.

- On display at the Victoria & Albert Museum & the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths.

- Since 2007 Jojo (wife) and Francesca (daughter) carry on the tradition with a limited collection.

Specialties

- Organic forms, textured wire

- Noted for texturing metal

- Molded metal into bold shapes

- Set large uncut gems and crystals based on color and shape rather than intrinsic value

1970

- Appointed jeweler to the Queen

Expansion

- e.1966 London

- e.1970 New York

- e.1971 Zurich

- e.1972 Tokyo

- e.1987 Lugano

- e.1992 Gstaad

Grima Maker’s Marks

- 1965 onwards – GRIMA alongside UK hallmarks

- Mid 1980s – onward the R and the A have the openings filled in (like the logo)

- 1946-1971 – HJCo – (H.J Company)

- 1971- Present – AG Ltd (Andrew Grima Ltd)

- 1987-1997 – TES (Tom Scott for Grima)

- 1986 Switzerland – GRIMA and 750 (no hallmarks because they were not made in the UK)

- Jewelry made for European jewelry houses was unsigned and later marked by the retailer.

Philip Grima’s Maker’s Marks

- G within a circle Philip’s mark since early 1980s

- Grima stamp similar but not identical

Sources

- Grant, William. Andrew Grima: The Father of Modern Jewellery. Woodbridge, Suffolk: AAC Art Books, 2020.

- https://grimajewellery.com/ Accessed 4/7/2025

- https://daphnecaruanagalizia.com/ Accessed 4/7/2025