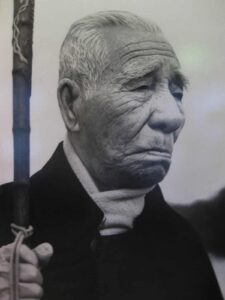

Kokichi Mikimoto was born in Toba, Japan on January 25, 1858. Born of humble beginnings he was forced to make his way in the world at a very early age, leaving school at age 11 to sell vegetables to help support his family. Adversity, however, did not dim his enthusiasm for beauty and for exploring. Since the arrival of Commodore Perry in the 1850s, outside influences had been filtering into the closed culture of Japan and Mikimoto found inspiration and opportunity in these changes.

In 1878, Mikimoto arranged a pearl judging exhibition and was appalled by the quality of the product being sold on the international market. He, along with his beloved wife Ume, set off to find a way to improve the quality of pearls in Japan.

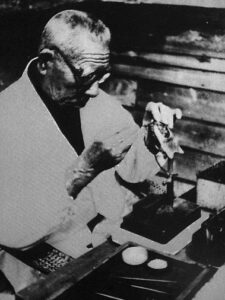

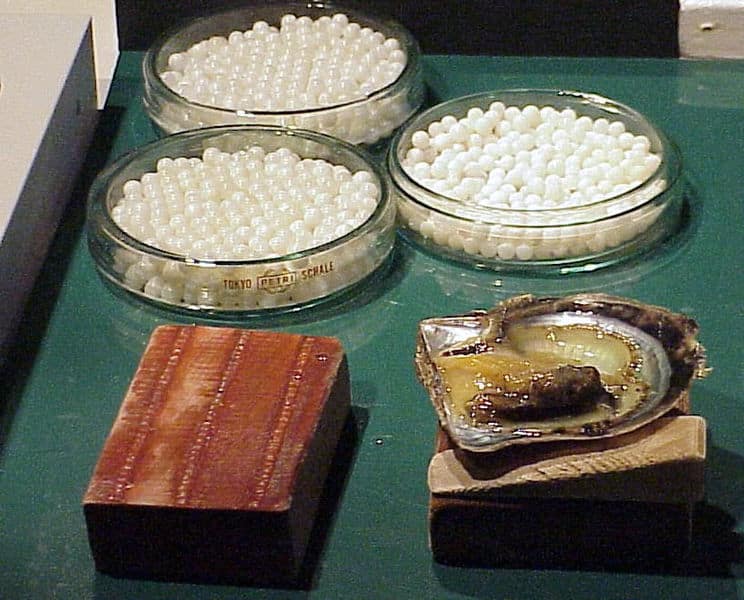

He learned that Akoya oysters produced the finest pearls and he explored ways to stimulate the nacre-forming process so that finer quality pearls could be produced. Beginning in 1888, many experiments were conducted, some successful and others, owing to oyster poisoning red tides and other natural adversaries, proved disastrous. On July 11, 1893, after overcoming all manners of trials, the first quality hemispherical pearls produced from Mikimoto’s experiments were successfully removed from their Akoya oysters. Mikimoto patented his process in 1896 and cultured the first fully spherical pearl in 1905. In 1908 he received another patent for culturing mantle tissue.

Such being their origin, pearls may be formed in any kind of Mollusc, bibalved or spiral. And just as the nacre of different kinds of shells differs, so the pearls themselves vary according to the shell which produces them. Thus the pearls of the common oyster, the scallop and the giant clam are milky white and not very bright, while those of the sea mussel are usually black. The chank and the conch shells, into whose pink mouth you have so often looked, produce the pink pearls which are brought from the Bahamas and the West Indies. These pink pearls are also found in several kinds of fresh-water mussels which are plentiful in some of the streams and lakes of America, Europa, China and Japan. Most superb of all, however, are the products of the true pearl oysters. These are the pearls which have always been called Oriental Pearls – “solidified drops of dew,” the poets have named them.1

Mikimoto continued to experiment and improve his process, setting up his base on Ojima Island with its new moniker “Pearl Island”. In 1916 a patent for culturing spherical pearls was applied for and granted. Mikimoto however, was not the only one working on the quest for a better-cultured pearl. In 1907 a patent was granted for the Mise-Nishikawa method of pearl culturing, which involved a bead nucleus and mantle tissue placed in the oyster’s gonad. Mikimoto’s technique of placing the bead into the mantle of the pearl (where natural pearls form) proved to be less commercially viable. Eventually, Mikimoto purchased the rights to the Mise-Nishikawa method, perfecting it and, up until Mikimoto’s experiments, the nuclei used to culture pearls were usually metal, often gold and silver beads.

What he discovered, through much trial and error, was that round beads carved from mussel shells originating in the United States were the best nuclei for round cultured pearls. This discovery was a significant contribution to the cultured pearl process and remains an integral part of culturing saltwater pearls throughout the world. The source for nuclei shells has only recently begun to shift from the United States to other countries.

A virtual marketing genius in the world of cultured pearls, Mikimoto opened his first boutique in Ginza in 1899. Word of the quality of the product sold there quickly made its way to Europe and by 1913, he had established stores in major cities across the globe.

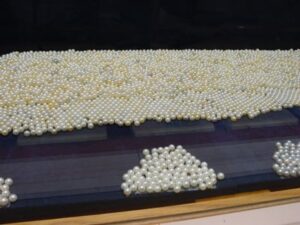

Always searching for ways to promote his product, Mikimoto participated in worldwide exhibitions such as the 1910 Anglo-Japanese Fair in London. Not content to simply display his pearls he always created a centerpiece for each of the exhibitions that would not be easily forgotten. At this first exhibition, a Japanese screen and fan embellished with Mikimoto cultured pearls impressed the attendees. The Mikimoto Pagoda at the 1926 Philadelphia World’s Fair continued to impress, featuring 12,000 gleaming cultured pearls set into a five-story pearl pagoda. In 1932, in order to reaffirm Japan’s superiority in the pearl industry, Mikimoto theatrically burned “inferior” pearls before an audience of the international press. At the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, a stunning miniature model of Mount Vernon embellished with 24,328 pearls was unveiled and at the New York World’s fair in 1939, Mikimoto displayed a gorgeous and crowd-stopping pearl model of the Liberty Bell.

Mikimoto strove constantly to build on the foundation he established with his high-quality cultured pearls. In 1930 the price of natural pearls had been so severely impacted by Mikimoto’s cultured pearls that the market for natural pearls all but collapsed. Further strain was put upon both the natural pearl and cultured pearl markets by the advent of World War II. While Mikimoto was able to keep his pearl farms open during the war years of the early 1940s, war disruption meant that natural pearlers could not work. The resulting pollution of oyster beds following the discovery of oil in the Persian Gulf and the migration of the workforce into other areas related to the war and oil exploration proved the final and fatal blow to the natural pearl industry. In the meantime, Mikimoto’s stockpile of cultured pearls insured a lively post-war cultured pearl market. Other Japanese pearl farmers, having learned Mikimoto’s techniques, joined the industry and post-war Japan adopted the cultured pearl industry as their “national heritage.”

Having established the first Black South Sea pearl farm in 1914, off Ishigaki Island, Mikimoto persevered to successfully culture his first South Sea Pearl in 1931, a dazzling 10-millimeter gem. In the post-war period, a much greater demand for larger South Sea pearls ensued and the pearl industry spread throughout the warm Pacific waters. However, the Japanese tightly controlled the nucleation, harvest, and sales of these magnificent gems. All pearls up to a size of 10mm were to be grown exclusively in Japan, only pearls larger than 10mm could be grown elsewhere. Mikimoto had thus secured control of the industry that had he created for his beloved Japan for decades after his death.

Recognized as one of Japan’s top ten inventors, Mikimoto was invited by the Emperor to attend a dinner at the Imperial Palace. In addition, he posthumously received the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Sacred Treasure. Mikimoto was active in the world of cultured pearls until his death in 1954 at the venerable age of 96.

Maker's Marks & Timeline

Mikimoto

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Era | e.1878 |

| Symbol | cartouche, frame, shell |

| Shape | cartouche, frame |

Specialties

1888

- Experiments began in pearl culturing.

1893

- First hemispherical pearls were produced.

1899

- First boutique in Ginza.

1913

- Stores established internationally.

1916

- A patent for culturing spherical pearls was granted.

- Mikimoto purchased the rights to Mise-Nishikawa method which he then perfected.

1931

- First South Sea Pearl was cultured.

1954

- Death of Kokichi Mikimoto.

- Mikimoto cultured pearls are still popular on the world market today.

- The leading pearl farms are in Japan, China, Australia & Thailand.

Sources

- Mikimoto. Copyright 2012. http://www.mikimotoamerica.com/

- Joyce, Kristin and Addison, Shellei. Pearls: Ornament and Obsession. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1993.

- Landman, Neil H., Mikkelsen, Paula M., Bieler, Rudiger and Bronson, Bennet. Pearls: A Natural History. New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History: The Field Museum, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001

- Mikimoto, K. Japanese Culture Pearls: A Successful Case of Science Applied in Aid of Nature. No. 3, Ginza-Shichome, Tokyo. 1907.

- Ward, Fred. Pearls: Bethesda, MD: Gem Book Publishers, 2002.

Notes

- Culture Pearls, p. 17-18.↵