Pearls are organic gems, produced in pearl oysters. Pearl oysters are not edible, and edible oysters do not produce gem-quality pearls.

When an irritating foreign particle becomes lodged within the oyster, it responds by covering the irritant with iridescent layers of nacre, a variety of calcium carbonate. Eventually, these layers build up to form a pearl.

There are a number of different types of pearls that are differentiated on the basis of their origin.

Akoya Pearls are cultured saltwater pearls that are cultivated from the species Pinctada fucata martensii, primarily in Japan and China. This was the first pearl to be cultured in a commercially accessible way.

Black Tahitian Pearls are produced in the black-lipped oyster (Pinctada margaritifera) This oyster is incredibly large, often measuring 12 inches across and weighing up to 10 pounds. It is found in French Polynesia and produces pearls with a naturally dark color.

South Sea Pearls are the largest cultured pearls in the world. They range in size from 9 to 20mm. The oyster that produces these pearls is called Pinctada Maxima. They live between the northern coast of Australia and the southern coast of China.

Freshwater Pearls are harvested from mollusks that live in lakes and rivers. China has been utilizing freshwater pearls since 2200 BC. Freshwater pearls are not bead nucleated, they are created by implanting muscle tissue into the mollusk. These pearls are solid nacre. Within the last 10 years, the quality of freshwater pearls has become so high that some may be indistinguishable from their saltwater relatives.

Keshi Pearls form in either saltwater or freshwater pearls. They are solid nacre and usually extremely lustrous. They form when an oyster rejects and discards the implanted nucleus before the culturing process is finished, or separate pearl sacs form that do not have nuclei. These pearl sacs ultimately create pearls without a nucleus. Keshi means “poppy seed” in Japanese, and these pearls are sometimes referred to as “poppy seed pearls.”

Mabe Pearls are grown on the inside of the oyster’s shell as opposed to inside muscle tissue. They are normally shaped like hemispheres with a flat back. They occasionally occur naturally, but most are cultured.

A Brief History of Pearls

For centuries, the Persian Gulf was the main source of pearls in the world. Records dating from 2300 BC document pearls as prized possessions of Chinese Royalty. In Egypt, mother-of-pearl was used as early as 4000 BC, but actual pearls are not documented until approximately 5BC.

The ancient Greeks and Romans valued pearls as symbols of wealth and prosperity. Indeed, throughout history, pearls have been amongst the most coveted of all adornments, parallel to the big four colored gemstones. Probably more than ruby, emerald, diamond and sapphire (in order of importance), pearls enticed the imagination of our ancestors

There were formerly two pearls, the largest that had been ever seen in the whole world: Cleopatra, the last of the queens of Egypt, was in possession of them both, they having come to her by descent from the kings of the East.1

Agnolo Bronzino 1545

Many legends on the origin of pearls, their owners, as well as their magical powers have been speculated on. The most enduring legend concerning pearls must be the wager between Queen Cleopatra and her lover, Marcus Antonius which took place in the first century BC and recounted by Pliny some 100 years later: Cleopatra baited Antonius with the promise of a meal that was to be the most expensive ever given. Antonius took the bet and on Cleopatra’s directions, a moderate banquet was prepared the following day. Her adversary for the day believed he had already won as there was not much out of the ordinary. The cunning queen then ordered a vessel of vinegar to be brought to the table and took off one of her pearl earrings. These were estimated at the time to be worth 60 million sesterces2 and were the most costly pearls the world had ever seen. She dropped the pearl in the vinegar – upon which it started to dissolve – and drank the beverage. The umpire, Senator Marcus Plancus, stopped Cleopatra from sacrificing the other pearl and declared her the victor. The tale does not alas, record the forfeit of the bet. However, this is an unlikely scenario, as anything that would dissolve a pearl would not be safe to drink.

Most ancient civilizations, from the Chinese to the Aztecs, used pearls as personal adornments. In Europe – specifically in the Roman Empire – pearls became fashionable from 61 BC when Pompey the Great held his victory parade over the defeat of Mithridates, King of Pontus (present-day Turkey on the Black Sea). Amongst the spoils of the war were numerous pearls set in crowns and other artifacts. After the Sack of Rome in the early 5th century by the Visigoths, these treasures were dispersed all over Europe and pearls remained fashionable at the various courts since. From the late Middle Ages, through the end of the 17th century, we can speak of “the age of pearls”. It was mainly the 30-year war (1618-1648) that caused the fashion for the prominent luxury of expensive pearls to be overtaken by a desire for a simpler, less ostentatious ornament.3 The popularity of pearls had actually begun to wane from around 1450 when faceted gemstones,4 especially diamonds, started to become available and partially overtook the role of the pearl. This is especially true in the 18th century when pearl production started to decline and imitations became available. The discovery of the Brazilian diamond mines in the early 1700s finally ended the pearl era. They remained associated though, with the sophisticated taste of old money, particularly in America after the Civil War of 1861-1865, where diamonds were considered the show-off stones of the day. Today pearls still carry the connotation of good taste and finesse as diamonds do of wealth.

Until very recently, it was inconceivable that a modern man would wear pearl strands, that has not always been the case. One can find many portraits of kings and princes overloaded with this organic material. It is actually difficult to find a royal that has not been portrayed with pearls in official paintings, either as necklaces or embroidered on hats and bodices. The Maharajahs of India were well known to lavishly adorn themselves with this wonder of nature well into the 19th century. The passion for pearls grew to such proportions that many European governments went so far as to issue regulations on who could wear them and when. A recent resurgence of men wearing all types of jewelry includes pearls along with other beads.

Cellini, never short of a strong opinion, didn’t think too highly of this popular gem and named them fish bones. Nevertheless, pearls were such an integral part of society during his time that he almost fell out of grace with his patron Cosimo I de Medici over a single strand of them. Cosimo’s spouse, Eleonora of Toledo, had her eyes set on the pearls and wanted Cellini to advertise them to her husband in order to receive them as a gift from him. Reluctantly Cellini praised the necklace but the Duke, who knew him well, finally got Cellini to express his true sentiments about the strand – much to the dislike of Eleonora. She finally got her way through an unscrupulous negotiator and it was only due to Cosimo’s affection for Cellini that he was not exiled from Florence, despite Eleonora’s wishes due to the “betrayal”.5

Until the middle of the 19th century pearls were either white or cream in color and it was not until approximately 1845, that colored South Seas pearls became available. They did not catch on until a decade later when Empress Eugenie of France brought them into fashion, though white pearls remained decidedly more popular. Although we generally name these pearls from the seas between Japan and Australia “South Sea pearls”, there is no South Sea in that area. The correct name should technically be “South Seas pearls”. Saltwater baroque-shaped pearls, named from the Portuguese word for irregularly shaped pearl, were used during the Renaissance as bodies of mythological creatures or animals. During the fin-de-siecle6 and the Edwardian period they came back in high fashion again although finding suitable forms, particularly in larger sizes, was difficult. The Edwardian period is also known as the “white period” due to the extensive use of pearls, colorless diamonds and white metals such as platinum. During this period, although pearl production had increased following the invention of diving regulators in the 1800s, prices greatly increased due to their high demand. Although there has been a good production of pearls throughout the ages, the largest pearls ever found in either salt or freshwater, are all baroque-shaped.

Seed pearls, so named for their smallness in size, were popular during the period between 1840 and 18607 when they were used to create 3-dimensional jewelry, strung together with very fine horse hair. Complete parures, including tiaras, were crafted this way. Often the pearls were sewn on a mother-of-pearl backing plate. Small half-pearls were produced by either sawing a semi-round pearl in half or by cutting them out of mother-of-pearl shells. In the late 19th century they were used extensively to decorate watch cases and other jewelry. Often these half pearls were placed on small disks of paper to level them out, so care should be taken when cleaning artifacts of this type. The centers of half-pearl creation were the German towns Idar and Oberstein (now named Idar-Oberstein).

Formation of Pearls

Pearls are a true wonder of nature and the result of a clever self-defensive mechanism employed by some types of mollusks, which we generally name “pearl oysters”. Most natural pearls form when an irritant – such as a parasite – enters the oyster and attacks it. The oyster surrounds the intruder with epithelial cells, forming a sac, and then secretes a mixture of nacre and conchiolin onto it. At that stage, the attacker is assumed to have died but the oyster still continues to deposit layers over it, and the pearl continues to grow until the oyster itself dies or it is removed from its body. Conchiolin is an organic material, that acts like glue, bonding the calcium carbonate layers of nacre. Pearls may also form when an irritant is trapped between the body of the animal and its protective shell, producing a pearl with one flat side, called a “blister” pearl.

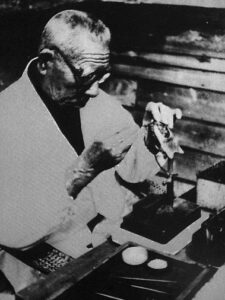

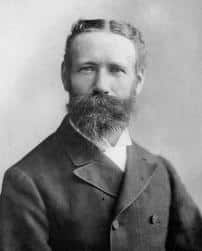

By the end of the 19th century several people, independently of each other, were experimenting with the production of round pearls. In particular Mikimoto in Japan and William Saville-Kent in Australia. In the first decade of the 20th century, a technique of creating round pearls was patented by two Japanese, Tatsuhei Mise and Tokichi Nishikawa and their method became known as the Mise-Nishikawa method. There are, however, strong indications that they may have learned the technique from Saville-Kent.

Mikimoto eventually purchased the rights to the method, perfecting it and achieving great success in marketing cultured pearls. This made pearls available to the general public for the first time. Pearl culturing eliminated the need for pearl divers and replaced them with pearl farmers. By the 1930s cultured pearls had become so popular that they all but halted the demand for natural pearls in most Western countries.

Today almost all pearls are cultured with just a fraction of them, mostly found in the East or in antique jewelry, being of all-natural formation.

Pearl is a birthstone for June and commemorates the 3rd and 30th Anniversary. It is the gem for Sunday.

Related Reading

Shop at Lang

Edwardian Large Natural Blister Pearl and Diamond Necklace

Pure opulence. This glorious Edwardian-era pendant is lavishly designed with a profusion of pretty details. Dangling from a pair of glittering single-cut diamon…

SHOP AT LANG

Art Deco Twin Natural Pearl and Diamond Bypass Dinner Ring - GIA

A gorgeous pair of gemmy lustrous natural saltwater pearls--one white, one light cream rosé--gleam from within mirror-image settings, in this fabulous Ar…

SHOP AT LANG

Gemological Information for Pearls

| Color: | All Colors |

| Crystal Structure: | Amorphous |

| Refractive Index: | |

| Durability: | May Scratch and Peel |

| Hardness: | 3.75 |

| Family: | |

| Similar Stones: | Synthetics, Plastics and Imitations |

| Treatments: | Bleaching, Dyeing |

| Country of Origin: | Australia, Japan, China, Mexico, South Seas and Many Other Localities |

Pearl Care

Pearls are very susceptible to heat and acids, in addition to being relatively soft and should be handled with great care. Interesting experiments in the 19th century established that pearls were very tough, however. They placed a pearl on a wooden board and stood on it, instead of breaking, the pearl remained intact and left an indent in the wood. It is not recommended though that one should try to reproduce these findings unless one is willing to sacrifice the gem in the interest of scientific inquiry.

Perfumes, which have existed at least since the 14th century, (Hungary water) have an alcohol base that is known to dissolve a pearl’s conchiolin, so care should be taken to wipe the gems clean with a damp cloth after wearing the two together.

Although pearls are accustomed to water, it is not advisable to place strung pearls in a hydrous solution to clean them. The threads may contain contaminants or dyes which may discolor the pearls through capillary action.

Always store pearls in such a way that they are not in contact with sharp or hard objects, such as other jewelry. They are best stored wrapped in a soft, uncolored, clean cloth.

Pearl Care

| Ultrasonic Cleaning: | Not Safe |

| Steam Cleaning: | Not Safe |

| Warm Soapy Water: | Safe |

| Chemical Attack: | Avoid (Even Perfume) |

| Light Sensitivity: | Stable in Natural Colors |

| Heat Sensitivity: | Unknown |

Sources

- Kunz, G.. The Book of the Pearl. The Century Co., New York, NY. 1908

- Cellini, B. The Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini. Translated By John Addington Symonds. 10th edition.

- Pliny the Elder, National history.

Gems & Gemology: The Quarterly Journal of The Gemological Institute of America.

Pearls:

- Summer 1936, Cultured Pearls, p. 27, 3pp.

- Spring 1938, The Bombay Pearl Market, p. 159, 2pp.

- Fall 1938, Abalones and Their Pearls, p. 187, 2pp.

- Spring 1942, Natural Pearls, p. 9, 4pp.

- Summer 1942, p. 25, 4pp.

- Summer 1943, The Pearls of Lower California and Mexico, p. 93, 2pp.

- Summer 1947, The Present Status of the Japanese Cultured Pearl Industry, p. 417, 4pp. (See also Winter 1947, p. 495, 1p.)

- Winter 1947, “Cave Pearls” or Pisolites, p. 503, 1p.

- Summer 1948, Pearl Fishing in the Persian Gulf, by Alexander, p. 38, 4pp.

- Spring 1949, Kokichi Mikimoto, Cultured Pearl Czar, by Foshag, p. 162, 1p.

- Winter 1950, Australian Pearl Divers, p. 379, 1p.

- Fall 1952, 1000-Year-Old Pearl Found in Yucatan Excavations, p. 227, 1p.

- Fall 1960, A 48.12 Grain Pearl Found in Illinois in 1960, p. 67, 1p.

- Winter 1961, Mr. S. Uda (Originator of Biwa Pearls) Speaks, p. 249, 2pp.

- Spring 1962, Freshwater Cultured Pearls, by Crowningshield, p. 259, 15pp.

- Fall 1963, Tridacna Pearls (Giant Clams) Show Flame Pattern on Surface, p. 89, 2pp.

- Winter 1963, Red Abalone Pearls, p. 102, 1p.

- Summer 1964, The Pink Pearls of Pakistan, p. 175, 6pp.

- Fall 1965, A Pair of 16mm Abalone Pearls (Green and Red), p. 333, 1p.

- Summer 1967, Cultured Pearl Farming and Marketing, p. 162, 11pp.

- Fall 1980, Gemlure: Born in the Depths: The Perfect Pearl, by Cheri Lesh, p. 356, 9pp.

Pearl Gemology:

- March-April 1934, The Scientist’s View of Cultured Pearls, p. 43, 2pp.

- July-Aug. 1934, Cultured Pearls said Not Genuine, p. 110, 3pp.

- -Oct. 1934, Pearl Tests, by Shipley, p. 136, 1p.

- Spring 1941, Pearl Colors, by Juergens, p. 139, 2pp.

- Fall 1941, Natural and Cultured Pearls (Their Differences), by Alexander, p. 169, 4pp.

- Winter 1941, p. 184, 5pp.

- Winter 1946, Radiographic Examination of Pearls, p. 359, 5pp.

- Winter 1946, New Pearl Essence Factories in Maine, p. 377, 1p.

- Spring 1947, Pearl Identification by X-ray Diffraction, p. 387, 5pp.

- Summer 1947, p. 428, 8pp.

- Fall 1947, p. 471, 4pp.

- Winter 1947, p. 508, 5pp.

- Fall 1947, The GIA Pearlscope, by Shipley, p. 462, 3pp.

- Spring 1950, Notes on Pearl Imitations, p. 288, 1p.

- Fall 1950, Reverse Pattern on Half-Drilled Black Pearls, p. 353, 1p.

- Fall 1950, Artificial Pearls Made By New Process, p. 353, 1p.

- Winter 1951, Gem Trade Lab Gets New Pearl X-ray Machine, by Benson, p. 107, 6pp.

- Winter 1951, Testing Drilled Pearls With Ultraviolet Light, p. 367, 1p.

- Winter 1954, Weight Estimation of Pearls (Chart and Formula), p. 99, 8pp. (See also Spring 1955, p. 157, 1p.)

- Winter 1954, Kokichi Mikimoto Dies (His History in the Pearl Industry), p. 108, 15pp.

- Fall 1955, Electron Microscope Sees Aragonite Crystals in Cultured Pearls, p. 215, 4pp. (See also Winter 1955, p. 254, 1p.)

- Spring 1958, Imitation Pearls, by Webster, p. 144, 4pp.

- Summer 1959, Clam pearls, p. 293, 1p.

- Fall 1959, Coque de Perle (Center of Nautilus), p. 342, 2pp.

- Winter 1959, A Natural Pearl with Black Spot in a Circle, p. 357, 1p.

- Spring 1960, A 17 x 14mm Dyed Black Cultured Pearl, p. 10, 1p.

- Summer 1960, Testing Black Pearls (Natural and Dyed), by Benson, p. 53, 6pp.

- Fall 1960, More on Testing Black Pearls (Natural and Dyed), by Benson, p. 75, 6pp.

- Winter 1960, Testing Rose Pearls (Natural and Dyed), p. 114, 1p.

- Spring 1961, An 11.8mm Pearl, Violet-Rose by Night, and Green by Day, p. 144, 1p.

- Fall 1961, Mabe Pearls, p. 216, 4pp.

- Fall 1961, A Huge Abalone Pearl, p. 220, 2pp.

- Fall 1961, Reaction of Pearls to Vinegar, Colognes, etc., p. 222, 2pp.

- Winter 1961, Spectrum Recognition of Natural (and Dyed) Black Pearls, p. 252, 4pp.

- Summer 1963, Coque de Perle (Center of Nautilus) earrings, p. 40, 1p.

- Fall 1963, Testing Black Pearls, p. 88, 1p.

- Winter 1963, Bleached and dyed cultured pearls, p. 99, 2pp.

- Winter 1963, Red Abalone Pearls, p. 102, 1p.

- Winter 1964, Cutting a Pearl in Half to Make a Pair, p. 247, 2pp.

- Spring 1965, Mallorca and Imitation Pearls, by Pough, p. 273, 8pp.

- Spring 1965, Surface Conditions on Conch Pearls, p. 281, 2pp.

- Spring 1966, A Pearl, Half Black and Half White, p. 24, 2pp.

- Spring 1967, Irradiated Cultured Pearls, p. 153, 2pp.

- Winter 1967, Hammered Effect on Pearl Surfaces, p. 251, 2pp.

- Fall 1969, Tissue-Graft Pearls, p. 91, 2pp.

- Spring 1970, Flame Like Pattern on Conch Pearls, p. 151, 2pp.

- Spring 1970, Black Cultured Pearls, p. 156, 2pp.

- Fall 1970, Gaps in Cultured Pearl Nacreous Layers, p. 230, 3pp.

- Summer 1971, Structure of Clam Pearls, p. 315, 2pp.

- Spring 1972, Cultured Pearl Ring Found, Outer Layer Worn, p. 21, 1p.

- Summer 1972, A Blue Mabe Pearl (Inside Filled with Blue Pitch-Like Substance), p. 41, 1p.

- Summer 1973, Canned Oysters with Cultured Pearls, p. 188, 2pp.

- Winter 1973, An Egg-Shaped Clear Yellow Conch Pearl, p. 235, 1p.

- Spring 1975, Pink Conch Pearls in a Necklace, p. 14, 1p.

- Fall 1977, Untreated Black Cultured Pearls, p. 348, 1p. (See also *Winter 1978, p. 365, 1p.)

- Winter 1977, Black Cultured Pearls, Natural Color, p. 365, 1p.

- Spring 1978, Differentiation of Black Pearls, by Hiroshi Komatsu and Shigeru Akamatsu, p. 7, 9pp.

- Spring 1979, Biwa Pearls, Black Pearls and Imitation Pearls, p. 147, 3pp.