Paul Flato, one of the more fascinating characters in American jewelry history, designed jewels that were as inventive and flamboyant as their creator. Catering to the tastes and whims of the very wealthy and the stars of Hollywood, Flato flourished at a time when high society dressed to impress and had no qualms about spending large sums on personal adornment. Advertising in top fashion magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, attending and hosting fashion shows, charity events, and evening balls, and establishing elegant stores in New York City and Los Angeles, Flato inhabited his client’s world, keeping his business relevant and in demand.

His subsequent downfall seems all the more shocking, but his optimistic nature and determination ensured that his story remains imbued with glamor, intrigue, and beautiful creations. Herewith, a brief summary of the jewelry and the rather incredible career of Paul Flato.

Born in 1900 into a prosperous family in Shiner Texas, Paul Flato enjoyed a privileged upbringing, exposing him from childhood to a world of elegance and a society that had the means to dress and adorn themselves. In the fall of 1920, he left Texas as an ambitious young man to study business at Columbia University in New York City. Following his first year in the city, he was cut off from his family allowance after declining entreaties to return home. Always interested in jewels, he took a job at a jewelry and watch dealer, Edmund Frisch, to support himself. Flato’s outgoing personality served him well and using his wealth of connections he was soon able to branch out on his own, opening his own salon on W 57th St.

His earliest sales concentrated on increasingly rare strands of matched natural pearls and designs featuring large diamonds. A prime example of one of his more important pearl strands, sold in 1930, consisted of eighty-five graduated natural pearls clasped by a four carat Golconda diamond. Flato’s most notable diamond supplier in the late 1930s was, a then relatively unknown but ambitious diamond dealer, Harry Winston. The most famous of their collaborations was the necklace that Flato designed in 1938 to compliment Winston’s 125.65 carat Jonker diamond.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Flato’s jewelry ran the gamut from elegant, important jewelry to urbane and slyly witty pieces. Central to his enduring legacy was his talent for employing gifted designers, including several high society notables. His chief designer, Adolph Klety specialized in creating the more formal platinum and diamond jewelry, rendering floral and naturalistic flexible jewels in a style that Flato memorably described as “drippy.” George Headley, another of his featured designers, was known for creating fanciful gold jewelry and accessories.

Elizabeth Bray describes a particularly imaginative piece designed by Headley in her book on Paul Flato:

His designs were often theatrical and conceptual. One piece that he created was a necklace of particularly romantic design. The giver of the necklace would write a love letter on a sheet of gold, the jeweler would then “tear” the sheet into fragments and assemble them on a chain. The receiver of the necklace could reassemble the pieces together to read the original letter.1

While Flato did not have the design training and drafting skills of Klety and Headley, he had a firm sense of how he wanted his pieces to look and gave instruction and guidance accordingly. His colored gemstone pieces reflect his strong sense of striking color combinations.

Flato also employed the design talents of two incomparable socialites: legendary style icon and Standard Oil fortune heiress, Millicent Rogers and former Vogue editor and wife of James V. Forrestal (Secretary of the Navy,) Josephine Forrestal. Based on Rogers’s sketches, Flato designed a series of well-received “fat heart” brooches in the 1930s. The most iconic of these was a dramatic large ruby heart featuring a sapphire swag with the motto “verbum carro” (the word made flesh) pierced by a yellow diamond arrow which was worn extensively by Millicent Rogers. Josephine Forrestal’s contributions included designs based on older antique pieces that she brought back from her extensive travels in Europe. Perhaps most well-known are her “wiggly clips,” diamond brooches based on nineteenth-century en tremblant jewels.

The most famous designer associated with Flato, however, was Fulco Verdura. Introduced to Flato by the fashion doyenne Diana Vreeland after leaving Chanel, Verdura designed a number of bold, colorful pieces that reflected a shared sense of aesthetics and exuberance. Opening his own boutique in 1939, Verdura continued to design glamorous jewels for many of the same famous clientele he had cultivated while working with Flato.

Elizabeth Bray notes:

Both men liked the shocking use of color and nontraditional subjects, and both were social and charming. Flato, like Verdura, was intrigued by religion and the supernatural. Both men liked to use angels, mythological and astronomical imagery in their designs, and both appreciated a sense of humor and whimsy in jewels. Verdura’s pieces had such cachet and presence that Flato began to market them “Verdura for Flato.”2

Photo courtesy of Christie’s.

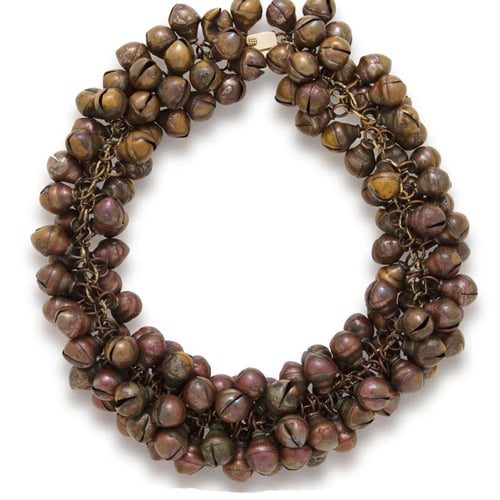

Flato’s wit and imagination were displayed in such original pieces as his series of gold sign language brooches. These “Deaf and Dumb” brooches, thought to have been inspired by Flato’s own hearing impairment, were elegantly adorned with red enamel nails and jeweled cuffs and were worn in pairs as monograms. Other unexpected subjects, often echoing the surrealistic movement of the early twentieth century, included such disparate subjects as feet, nuts and bolts, envelopes, gold boxer shorts, radishes and cacti that were transformed into brooches, cuff links, boxes, and earrings.

In 1938 Flato opened an elegant store in Hollywood opposite the famed Trocadero supper club where his designs were well suited to the glamorous stars and high fashion of the film industry. Forging both personal and professional ties, Flato’s jewels were credited in five Hollywood productions and worn by such stars as Rita Hayworth, Greta Garbo and Katherine Hepburn.

Many of his pieces during this era reflected the forties-era trend for large-scale, convertible jewels that could be worn in multiple ways. Two noteworthy examples were Marlene Dietrich’s 128 carat cabochon cut emerald and diamond bracelet in which the emerald could be removed and worn as a rather imposing ring and Joan Crawford’s cabochon cut ruby and diamond necklace designed with Verdura, which could be converted into bracelets, a pendant and dress clips.

While the jewels proved enduring, this chapter of Flato’s glamorous professional life came to an ignominious and improbable end worthy of a Hollywood screenplay. Flato’s downfall started when the loss of a consigned 17 carat emerald cut diamond in his New York location exposed a series of ill-advised financial decisions to surreptitiously sell off consigned goods to raise cash. Unable to return the goods or pay off consignors, Flato was ultimately convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to 18 months at the notorious Sing Sing prison starting in December 1943. A brief foray into producing fashion compacts and pens followed his release from Sing Sing. A short time later he allowed himself to fall under the influence of an unscrupulous fortune teller and once again reverted to the same unsound and illegal methods of securing funds. In an attempt to avoid another stay at Sing Sing, Flato fled to South America. In a futile effort to escape extradition, Flato pled guilty to lesser, unrelated charges in Mexico and ended up with a four-year term at Mexico’s Lecumberri prison before ultimately serving a second five-year term in Sing Sing.

Surprisingly undaunted, Flato returned to Mexico for the last chapter of his remarkable career. Opening a store in Mexico City’s Zona Rosa section in 1970, Flato continued to design remarkable jewels for the next twenty years, many of which referenced Mexico’s indigenous culture and Flato’s love of exuberant color combinations. In 1990 at age 90 Flato retired to Texas to be near family and friends. He regaled them with tales of the jewelry he created, the famous stars and clients he adorned and all the illustrious (and not so illustrious) places he had lived until his death on July 17, 1999.

Maker's Marks & Timeline

Flato

| Country | |

|---|---|

| City | Beverly Hills CA, Mexico City, New York NY |

| Era | (1900 – 1999) |

Specialties

1920s

- New York

- Designers included Adolph Kleaty, George Headley and Fulco di Verdura

- Whimsical Jewelry “Say it in Jewelry”

1937

- Beverly Hills Location Serving Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich and others

1970

- Mexico City

Sources

- Bray, Elizabeth Irvine. Paul Flato: Jeweler to The Stars. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collector’s Club, 2010.

- Proddow, Penny & Debra Healy. American Jewelry: Glamour & Tradition. New York: Rizzoli, 1987.

- Proddow, Penny, Debra Healy & Marion Fasel. Hollywood Jewels: Movies, Jewelry, Stars. New York: Harry N.Abrams, Inc., 1992.