Earrings are much more than just decorative jewelry for the ear. Gods and goddesses, symbols, talismans and amulets have all been depicted in the designs fastened to or suspended from the ear giving the wearer a feeling of power, safety, kinship, and loyalty. Pearls tinkling gently, magnificent gems twinkling below the lobes or the tug of weighty gold ear bobs all create an outward display of success and wealth. At times they have been a tool for secret communication as illustrated by Madame de Soubise’s use of a pair of emerald and diamond earrings, a gift from Louis XIV, to signal the king that her husband was away and they could have their tryst. While shapes, styles, materials, and symbolism may have fluctuated endlessly, earrings have, with a few exceptions, been popular since we began to adorn ourselves. The first archaeological earring finds date from the third millennium B.C., but we can be sure that earrings from earlier eras simply did not survive the test of time.

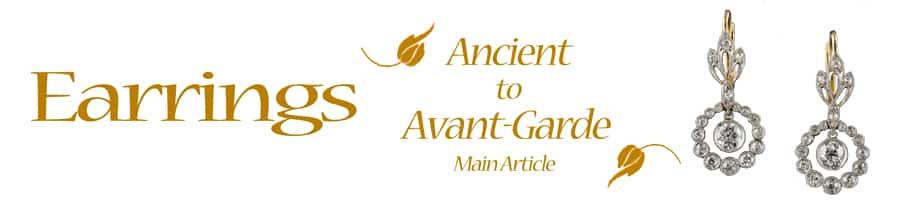

It is not surprising that the earliest earrings extant from ancient civilizations would be from the Sumerian city of Ur in Southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) – the cradle of civilization. Royal Sumerian graves are the source of discovery for vast quantities of ancient jewelry, including earrings. The Sumerian Renaissance represented cultural advances in technology and the tools to create great art. The sexigesimal counting system, which gives us our 60-second minute, 60-minute hour and the division of day and night as 12-hour periods, came out of this enlightened era. Sumerians conceived the concept of a ‘work day’ with holidays and resting days and too many other “firsts” to enumerate here.

c.2500-2000 B.C. Western Asiatic.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Since Sumer was not a gold-producing region, artisans cleverly stretched the small amount of gold that was available by pounding it into very thin sheets. These paper-thin gold foils, when soldered and rolled, created a lightweight, hollow-centered crescent-shaped earring. Masterful use of filigree and granulation was employed along with embossing to great decorative effect. The Sumerian’s ornamental skills resulted in earrings that gave the illusion of greater mass. After the fall of Ur c.1750 B.C., her citizens migrated to far-off civilizations spreading the legacy of their discoveries.

c. 13th Century B.C.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

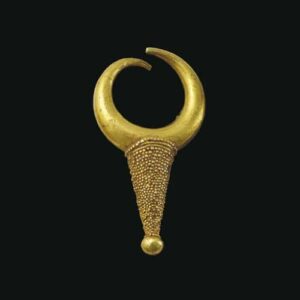

The Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations were known to have traded with Egypt and the Middle East. Indeed, they had paved roads to connect them to major cultural centers. As a result of the extensive trading networks, they had adequate access to gold along with copper, tin and ivory to create jewelry and decorative objects. The earrings produced during the Protopalatial Minoan Crete era (1900-1700 B.C.) were tapered hoops with overlapped ends. During the Neopalatial (1700-1400 B.C.) and Postpalatial (1400-1150 B.C.) periods, we see more scalloped and tapered hoops. The introduction of a conical pendant with twisted and braided wirework begins a new style of earring, no longer composed of just a hoop but having a suspended, moving ornament.

c.1700-1500 B.C., Minoan.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

After the fall of the Mycenaean and Minoan civilizations, their cultures were assimilated into the new Hellenic culture, which would further evolve to become the Classical Greek civilization. Beginning circa 1100 B.C. there was a dark period when the jewelry arts all but disappeared. There was no longer easy access to gold and other vital jewelry-making materials, but in spite of this hardship, goldsmiths continued their work in the Mycenaean tradition enabling the designs and motifs to be rediscovered in Greece in the seventh century B.C.

c.1300-1200 B.C., Cyprus.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Egyptians did not embrace the idea of adorning their ears until they had firmly established the custom of wearing other forms of jewelry. Earrings began to appear in Egyptian culture around the time of the New Kingdom (1559-1085 B.C.) This was the era of the reign of the great pharaohs, among them: Ahmose (first to rule without opposition,) Tutankhamun, Hatshepsut, Akhenaten and Nefertiti. Egypt was reunified and exploration, expansion, and trade brought great wealth to Egypt. Egyptian art underwent a revolution exchanging strict rules and conventions for more realistic human renderings. Outward expressions of personal wealth were prevalent and included extravagant jewelry.

c.1370-1250 B.C., Egypt.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Worn by both women and men, Egyptian earrings were quite different from those worn in other parts of the world. Large cylindrical earplugs made of faience or caned glass were grooved to fit snugly within a stretched earlobe. There were also very large stud-like earplugs with a flat larger front piece and a thick rod on the back that pushed through severely stretched lobes securing the earring. Large-scale production of colored glass for jewelry manifested in several varieties of penannular glass hoops. One style had a narrow opening between the ends of the hoop in which an earlobe could be squeezed, using pressure and tension to hold the hoop in place. A very similar glass hoop with additional holes at either end allowed for the passage of a wire hoop through the earring and through the lobe.

Burial sites also provide evidence of very large metal triangular-section multi-tubed hoop earrings that either required a piercing or squeezed the lobe within a “pressure” gap between the ends. The difference being that the pierced version had a longer central tube that passed through an oversized piercing in the lobe. Other 18th Dynasty styles included gold sheet formed over a pre-shaped core resulting in a leech-shaped earring with wirework accents that cleverly concealed the seams, and drop and disk earrings that could suspend an elaborate pendant or pendants.

c.450-400 B.C., Greece.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Ancient Greece introduced the world to the importance of government, philosophy, the arts, and science. Much of our documentation for style and fashion comes from the minute detail in the paintings, sculpture, mosaic and other art forms. In Greece, circa 700 B.C. earrings are depicted in the crescent shapes so common during the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations, complete with wirework and granulation. Spiral-shaped earrings with griffin or ram’s heads were another favored motif. The gold being supplied from the East inspired Greek goldsmiths to create more elaborate, larger and more three-dimensional earrings than were ever possible before. By the 5th century B.C. popular disk earrings added dangling pendants, feminine heads, inverted pyramids with link chain supports and amphora. Also during this period, gemstones began to appear as decorative elements on earrings and soon they became a featured motif.

550-450 B.C., Umbria.

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Similar developments were happening in the Etruscan region with crescents and hoops predominant. By the 6th century B.C., the baule style began to appear. This was a strip of gold worked into a “U” shape and suspended from a gold wire, reminiscent of an open-top bag. Extraordinarily excessive amounts of granulation and wire work, forming natural elements, decorated the earrings, punctuated by enamel and glass inlay with amber and other gems contributing to the cluttered designs. By the 5th century, a longer-lasting style had evolved which consisted of a tubular hoop with figural designs.

1st Century A.D.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Disc-style earrings overlapped this period and remained popular for the next four centuries. Filigree, embossing, opus interrasile and granulation were employed to create the floral and geometric motifs accenting these large discs. Eventually, pendants were added, slowly evolving until the discs disappeared and the pendants were all that remained of the style.

Rome absorbed and adapted much of Greek knowledge, philosophy and art, therefore, the early Roman era did not exhibit any particular “Roman” style. Circa first century A.D. earrings were featuring a hemispherical design with an “S” shaped hook. During the second-century large bezel-set gemstones suspended gem or pearl pendants from horizontal elements. Pendants were hung in duplicate or triplicate to employ the concept of Crotalia, literally defined as ear-rings from the “ringing” sound made as the suspended pendants clicked together with movement.

Byzantine, Medieval, and Renaissance Eras

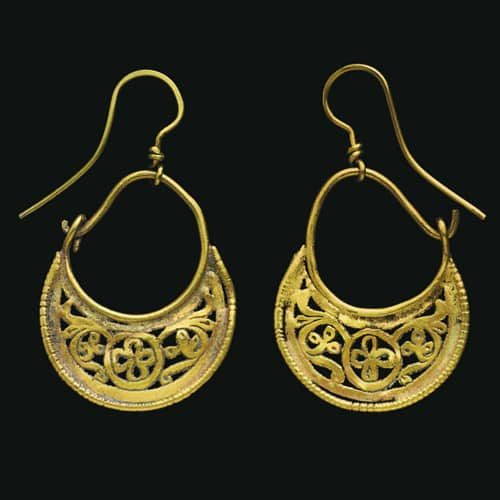

After the fall of the Roman empire in the west, the eastern empire, ruled from Constantinople, was left with a decidedly Roman influence in jewelry, including earrings, but an eastern (more Asian) flavor began to be observed in other Western arts. The Byzantine period, which extended beyond the fall of Rome for another millennium, saw fashion evolve to the point where it was again nearly devoid of earrings. It became customary to wear decorative ornamental elements at the temple or the side of the face secured in the hair or suspended on a ribbon or chain. The earrings that remained reverted to the earlier crescent-shaped openwork floral and filigree motifs, often disguising religious symbolism.

© Victoria & Albert Museum.

Jewelry, sans earrings, flourished during the Middle Ages and on into the Renaissance. In the West earrings were becoming more and more scarce and by the Middle Ages, especially between the eleventh and the sixteenth centuries, they had nearly completely vanished. Several factors influenced the de-evolution of earrings. There evolved a fashion for coiffures that covered the ears, hiding them completely from view. By 1300 the hair was firmly netted and confined by an ethereal veil or gem-set net glamorously ensnaring the hair, often containing additional “false” hair and curls.

In addition, pearl strands were often wound around the head, effectively entrapping the ears, while adorning the pate. The mores of the period also had an influence, requiring respectable, married women to keep their heads covered and their hair concealed by wearing various elaborate headdresses from turban styles to steeple caps and veils. These complicated creations often sat atop a broadband covering the ears that tied under the chin. Between the concealing hairstyles, towering hats and headdresses and fashions that saw collars rising to new heights, earrings became an unnecessary accessory.

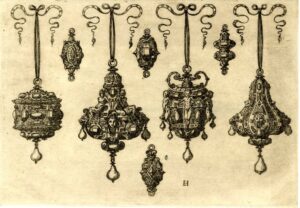

c.1585-1640, Great Britain, UK.

Victoria and Albert Museum Collection.

Actual earrings re-appeared in Italy c.1530s. The first style was a simple hoop suspending a pearl drop followed shortly by a style that had the pearl drop tied to the earring via a ribbon, usually in a shade to compliment the dress. Spain also had some influence with regard to fashion’s re-embracing of earrings. The Spanish custom was to wear one large ornate jewel and supplement it with a pair of matching earrings. It was also popular among the Spanish for men and women to wear a gold pierced hoop through the ear on which to suspend a pearl or gemstone pendant. Later lacier, elongated filigree earrings in the Spanish style began to appear in England. Both men and women at the Court of Queen Elizabeth are depicted as wearing earrings, usually with large pearl drops dangling from modest hoops, or earrings of other gems also hung singly or in triplicate from either one or both ears. Circa 1600 the standing collar replaced the ruff and earrings were on view once again.

1562, Germany.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

In a book by jeweler Arnold Lulls (1585-1621) of the Netherlands (James I of England was a devotee) earrings, after their long absence, were once again featured. With thanks to the burgeoning gem-cutting industry, earrings began to feature faceted gemstones. Hoops with a central (usually circular) element and a pear-shaped drop soon evolved into much more complex triple drops, which morphed into the girandole style, that swept the fashion world and remained for centuries. The ribbons used in an earlier time reappeared, this time rendered in metal as gem set bows and ribbons supporting trios of pear-shaped drops.

Earrings were once again essential. By the mid-seventeenth century, earrings were an undisputed element in every jewelry parure. They grew ever more elaborate with fringe, pearls, gems and enamel. The popularity of floral motifs followed the tulipomania that swept Europe. There was also a brief fashion for threading black cord, tied to create eye-catching loops and bows, through the earlobe to support a small pendant and an equally brief penchant for mismatched or single earrings.

Men of the period were often depicted with great swagger wearing only one earring. It is reputed that James I was repulsed by the sight of men wearing earrings but, strangely enough, his courtiers seemingly had no fear of any retribution and are depicted in their portraits with earrings. Sir Walter Raleigh is said to have worn two pearl drops in one ear with great aplomb. This fashion lasted until the end of the reign of Charles I in 1649. Charles famously followed the masculine fashion for one earring in direct opposition of his father’s immense dislike of the custom. The fate of his iconic single pear-shaped pearl earring, after his infamous beheading, is the source of some conflict. One version of the story has him handing it off to a friend as he ascends the scaffold steps and another version features him wearing it until the end, the earring removed after death and given to Mary, Princess Royal.

Eighteenth-Century

Painted 1762 Thomas Frye

Photo Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014.

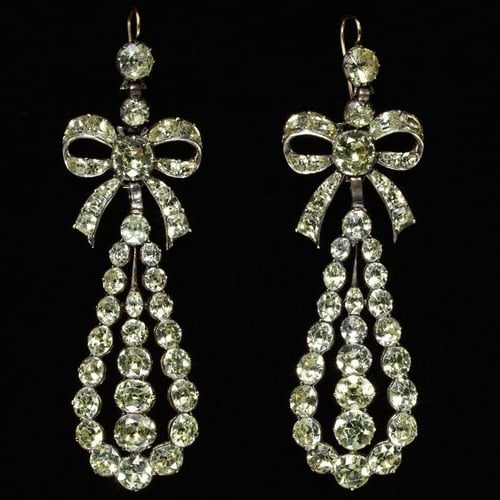

Girandole earrings continued to dominate in the Eighteenth century with a few exceptions. The seventeenth-century enamel and engraved designs were replaced by a plethora of gemstones for evening and paste for day wear thus instituting a divergence between day and night jewelry. A passion for faceted gems, incited in part by the discovery in 1725 of diamonds in Brazil, coincided with an infatuation with candlelit evening soirees which provided a fertile setting for dangling, glittering earrings. Hairstyles were fantastically upswept exposing the sides of the face and the ears and, combined with plunging necklines, the stage was set for a resurgence of big bold earrings.

Earrings evolved to a more elongated form with the central girandole drop becoming noticeably longer than the other two. Eventually, the three drops of the girandole gave way to a singular elaborate drop, the pendeloque. Some of these creations were quite heavy, in part due to the extra metal used in the closed-back gem settings, which also fueled the popularity for the singular pendeloque style. Various devices were employed to alleviate the weighty burden including ribbons that tied earrings into the hairstyle and hooks that rested on the top of the ear. Openwork pierced lacy ribbon and bow motif central elements were used between the top and the drop of the earring in another effort to lighten the load. Elegantly long filigree earrings combining diamonds and colored gemstones, pearls and enamel were also very popular, especially in France. Hairstyles had ascended to new heights and these shoulder-dusting earrings were the perfect accompaniment.

Late in the century a simpler style that featured a large faceted gemstone, almost button-like and usually oval, suspending a smaller gem or pearl drop made a brief appearance. These “gemstone only” earrings did not survive the test of time presumably because the larger more valuable gemstones were re-used or modernized somewhere along the way. Girandole and pendeloque styles grew larger and remained in fashion as time marched onward into the nineteenth century.

c.1820.

Victoria and Albert Museum Collection.

Victoria and Albert Museum Collection.

In France, a dearth of gold and gemstones and the death of the guild system following the French Revolution caused the quality of jewelry to decline. Bold gold and gemstone jewelry did not fit with the newly espoused principles of egalitarianism so gold was pounded very thin and enamel or glass replaced precious gemstones. Style and quality suffered and very few designs survived. Button-shaped clump-type earrings were popular as well as oversized hoops and filigree.

After the revolution, a classical goddess look of translucent filmy dresses cut with clingy profiles (sometimes worn wet to enhance the look) were accompanied by large but flat, geometric earrings. These extremely light earrings were meant to flatter the wearer without flaunting any high-value gems or precious metals. The popular poissardes style had a hinged back ear wire that fastened into a loop on the front of the earring. The earrings themselves were openwork half hoops or flat fronts punctuated by paste and/or enamel. Another style was composed of extremely thin gold elements, sometimes decorated by grisaille enamel portraits or other images, connected by an elaborate system of delicate chains.

Nineteenth-Century

c.1830.

The Coronation of Napoleon ushered in the return of important jewels in France. Luxury was a requisite part of life at court and jewelry was commissioned by all who participated. Parures became the rule of the day. Matched sets of bracelets, earrings, necklaces, tiaras and other elements were all included in the beautifully fitted boxes that accompanied the well-heeled to court events. Enamored of the cameos he saw on the Italian campaign of 1796, Napoleon returned to France and opened a Parisian gem engraving school and cameos rapidly became the overwhelming fashion of the day.

Girandoles and pendeloques were still the reigning style for earrings. Filigree and cannetille, which required less gold to achieve a bold look, were popular techniques. These lightweight but showy earrings were set with paste and foilbacked semi-precious stones on the continent and with more valuable and robust gems in England. Earrings grew ever longer and by the 1830s they reached the shoulders.

A type of repoussé earring used thin sheets of stamped gold to create an elaborately embossed earring. Bold foliate and scroll motifs were possible with much less gold resulting in lighter and less expensive earrings. These repoussé designs were often decorated with multi-colored applied gold enhancements and gems or enamel. Simpler to make and still utilizing less gold, repoussé earrings soon seized the market from the more complicated cannetille designs. Aquamarine, amethyst, topaz and citrine gemstones were the preferred accompaniment except in England where agate drops were popular. Enamel plaques were used in place of gemstones in Italy and Switzerland giving an entirely different aesthetic to the same technique.

Antiquity

Another type of drop earring popular in England consisted of a drop-shaped frame studded with diamonds swinging a large pearl or other gem within and surmounted by a clustered foliate motif. Oval gemstone earrings suspending a simple collet set pear-shaped gemstone drop were featured until the 1840s.

Inhospitable hairstyles once again quashed the earring from about 1840 to the 1850s. A severe center-parted style that covered the ears and terminated in a knot at the back eliminated the need for earrings. The only earrings to appear at the Great Exhibition in London, 1851, were small and of a naturalistic motif. Oversized floral tiaras framed the face and provided the decorative element to replace the exiled earrings. The only regularly worn earring during this period was the dormeuse (sleeper) which usually consisted of a single stone, much like a modern ear stud. These were worn overnight to keep the pierced hole open awaiting the return of bolder earring styles.

Photo Courtesy of Bonhams.

The latter third of the nineteenth century the hairstyles went up, the earlobes were bare and women once again enjoyed wearing earrings. Jewelry was ensconced in a novelty phase and earrings were definitely included in this fun and frivolous fad. You name it, they wore it. Hammers and saws, buckets and wells, bows and arrows, real bugs, hummingbird feathers, snakes, and flowers.

This was also a time for amazing archaeological discoveries spawning a classical revival. The newly re-discovered ancient jewels were reproduced with intricate detail. Intaglios, coins, and other fragments salvaged at these historic sites were incorporated into newly made jewels of ancient inspiration. Tinkling Roman crotalia-inspired earrings reappeared suspended from more modern lobes. A Baule earrings of the Etruscan era were recreated with all their intricate detail. Classical themes of ram’s heads, amphorae, blackamoors, all with granulation and wirework enhanced by enamel, were the popular themes resurrected from the distant past. Intriguing materials began to appear in these revival designs. Hardstone cameos, micromosaics and Florentine mosaic along with carved lava, jasperware and tortoiseshell all made appearances in these new/old designs with a classical flavor.

Newly laid railways crisscrossed Europe and a “modern” breed of traveler set off on “The Grand Tour.” Returning tourists displayed their new found sophistication by means of souvenir jewelry. The casual observer could chronicle your trip by the motifs and materials used to create the jewels on display in your ears, pinned to your bodice or draped around your neck, wrist, and finger.

A unifying design element of the time was the oft included fringe dangling and swaying below the archaeological and Renaissance designs. English fringe (often referred to as bearded fringe) was composed of densely grouped strands of chain or tiny rods or cones tapering to a point, while the rest of Europe suspended three to five shaped elements spaced somewhat apart. Large cabochon garnets and amethysts were often topped with a star motif diamond or pearl inset and the star motif itself was used on simpler earrings and set with opals, turquoise, pearls and diamonds surmounted by archaeological elements and finished with fringe.

The use of en tremblant devices on floral and foliate motif earrings provided additional movement to the designs. Another innovation c.1890 was the screwback earring coming to the rescue of earring lovers when the custom of ear piercing came to be regarded as an uncouth practice.

Fin-de Siècle & Twentieth Century

As the century came to a close, earrings were left with nowhere to go but up. Although the piled high Gibson Girl hairstyle left the lobes bare, necklaces gained new heights with the popularity of the collier de chien and together with rising dress and blouse collars the passion for elongated earrings was quashed. Single stone or pearl ear studs and diminished “top and drop” styles were replacing the earlier bold pendant designs. Diamonds were plentiful with the South African discoveries and a demand grew for larger diamonds set singly. Colored gems were arranged in clusters with pearls to compliment the muted fabric tones of daytime wear.

The Art Nouveau movement was popular if not somewhat short lived. This stylistic revolution had a tremendous impact on the decorative arts, including jewelry, but did not produce much in the way of earrings. The competing guirlande or garland style in France, espoused by Cartier, and the Edwardian era in England were propelled to popularity by the advent of the use of platinum in the jewelry trades. New levels of lacy intricate designs were possible with platinum. The delicacy of the metal allowed the brilliance of the diamonds to transcend. Articulated ethereal floral and foliate earrings, accented by ribbons and bows, with millegrained details sparkled and glimmered with new fire. The longer earring styles and the increasing geometric details in their designs foretold the coming of the Art Deco Period.

Jewelry production went on hiatus with the onset of World War I. Gemstones were difficult to procure and platinum was necessary for the war effort. Women went to work and skilled jewelers traded their workbenches for important jobs in war-related industries. Once production resumed following the war, women’s fashions had changed drastically.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

The Art Deco era ushered in myriad innovations: Carved materials such as coral, jade and rock crystal were used along side precious gemstones and diamonds. Vivid colors were combined with geometric design and inspiration came from exotic lands such as Egypt, China, India, and Persia. Gem cutting and carving techniques from China and India were used to produced elaborately contrived plaques and interesting new shapes for rubies, emeralds, and sapphires. The combination referred to as tutti frutti made use of these exotically carved gems.

Diamond cutting was also continuing its evolution and many new shapes were created at this time. Baguettes, half-moon, triangular and other calibré cuts enabled gems to be fitted together in clever new ways. Pavé setting was used to completely cover a metallic surface with gemstones.

The extremely short, lobe exposing hairstyles cried out for long dramatic earrings. A cornucopia of inspiration from the past as well as from far-flung foreign lands resulted in girandoles, tassels, fringe and chandelier styles in combination with colorful carved hardstones in annular, cabochon and extremely elongated drop shapes suspended from diamond studded, delicate and elongated surmounts. As the 1920s gave way to the 1930s a reversal of scale took place and the diminutive dangling surmounts were replaced by larger more encompassing ones that suspended a removable, more delicate, fringe or tassel.

These swaying and somewhat fragile earrings required a secure grip on the lobe not to mention an invisible mechanism. The screwback was not up to the task so a pierced stud with a hexagonal spring-loaded backing was developed to hold the earrings securely. In the early 1930s, a clip-back lobe gripper was patented and heavy gold combinations with large single gemstones and smaller clusters, gold disks, scrolls, flowers, and ribbons could now be clamped securely onto the ear.

Gold returned with a vengeance in 1940. Platinum was once again a necessary metal for armament production and gold was scarce, and in some cases restricted. Lower karat gold and re-cycled gold were used sparingly along with re-purposed gemstones, another scarcity brought on by the war. Ear clips were the most sought after with large citrines, amethysts, topaz and aquamarines paired with very small rubies and sapphires, often of synthetic origin. The harsh lines of the 1920s and 1930s gave way to softer natural themes; floral, foliate and flowing ribbons and bows were the predominate motifs. Pendant earrings were a variation of the clip earring created by adding a tassel or chains with small terminal elements.

After the war folks were anxious get their lives back to normal and prosperity was the watchword of the 1950s. Earrings were more open and fluid, the still popular ear clip was re-designed to mirror the shape and curve of the earlobe and to dangle articulated fringes of the ever popular diamond. The predominance of diamonds and pearls ensured the return of platinum in the form of palladium to compliment these “white” gemstones and to provide structure without weight. Pierced ears were just “not done” by the newly well-to-do and ear clips and screwbacks ruled the marketplace. Yellow gold was relegated to daytime wear with fantastic tassels, and twisted wire motifs manipulated in fun and fanciful ways.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw a rejection of any rules with regard to jewelry. The concept of what was appropriate for day or night wear was thrown out the window and earrings, like other jewelry, followed the fashion world with regard to forms and colors. The 1960s saw the use of whimsy including fanciful shells and colorful enamel on oversized earclips. In the 1970s pierced earrings were acceptable again facilitating the popularity of stud earrings and various hooped styles. Earrings for men were enjoying an encore after a very long period of the practice being taboo. Styling for earrings had come full circle and bold archaeological motifs were once again in vogue and, during the 1980s and 90s, a virtual rainbow of colored gems were employed in increasingly intrepid designs.

Although the dictates of fashion, in combination with constantly competing hairstyles, tried in earnest to quell our desire to adorn our lobes, earrings won the day. Some of the most complex innovations in jewelry mechanics came from the overriding quest to hang earrings by any means possible. It’s as if earlobes were planted on either side of our faces for the sole purpose of personal adornment via the suspension of all manner of gems, precious metals, and innovative designs.

Sources

- Bradford, Ernie. Centuries of European Jewellery. Norwich, Great Britain: Country Life Ltd., 1953.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714 – 1830, Woodbridge, Suffolk England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Evans, Joan. English Jewellery: From the Fifth Century A.D. to 1800: London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. 1921.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Mascetti, Daniela and Triossi, Amanda. Earrings: From Antiquity to the Present. Rizoli International Publications, Inc. New York, 1990.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Tudor and Jacobean Jewellery. Tate Publishing, Trustees of the Tate Gallery. 1995.

- Tait, Hugh. Seven Thousand Years of Jewellery. London: British Museum Press. 1986.