Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Modernism is an umbrella term used to encompass all the diverse artistic movements throughout Europe and America from circa 1880 to circa 1960 and beyond. Artisans of the late nineteenth century looked at revival design as sorely lacking in new ideas, simply regurgitating earlier designs for a new generation.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Each of the following periods in design history encompassed a rebellion away from the mass-produced home goods and personal items of everyday life. The Industrial Revolution was the cause and the artisans saw their “movement(s)” as the solution. A common thread running through each of these movements was the idea that design did not exist in a vacuum but could be shared among all the decorative disciplines. Included was everything from wallpaper, carpets, lamps, fabrics, flatware, holloware, trophies, knickknacks, furnishings, and jewelry, all created and curated so that the ultimate benefit of the aesthetic could be achieved. Drawing on a collection of artistic specialties including architecture, the new field of graphic design, metalwork, and industrial design, an original perspective was achieved. Along with a new century came an entirely different way of looking at everything man-made in our world.

Another common decree by the artistic rebellions that followed was abstention from historical plagiarism with total rejection of historical design revival. One notable exception was the Celtic revival popular during the Arts and Crafts movement. Going a step further many groups advocated an altruistic principle embracing all things handmade. This directive fluctuated from movement to movement but was integral to many of the artistic manifestos espoused by the factions discussed here. Increased consumerism eventually spurred the need to embrace the use of machinery to meet demand and to realize production in a fiscally responsible way.

As with most attempts to put a start and end date on an artistic movement, this time constraint should be considered elastic. For the purpose of this article, each movement is arranged as chronologically as possible.

Arts & Crafts 1875-1915

The Arts & Crafts Movement in England, which also enthusiastically crossed the pond to America and sparked many off-shoots in Europe, emphasized aesthetics and the importance of handicrafts. The improved well-being of the workers had a desirable side benefit. The Medieval model that utilized communal workspaces and guilds to produce all manner of goods was essential to the movement. Design innovation and the sharing of ideas, techniques, and skilled workers resulted in a new look and often a new form to everyday items adding a dimension of beauty to the consumer’s everyday life.

Ultimately, competition from department stores and mail-order catalogs made it difficult for the Arts and Crafts artisans and guilds to compete in the fast-paced burgeoning consumer culture at the turn of the Twentieth Century. 1 In America at least, the use of machinery in the production of goods with the Arts and Crafts aesthetic was seen as necessary to be able to compete in this fast-paced market. Frank Lloyd Wright spoke to the Chicago Society of Arts and Crafts in 1901 asserting:

“Machine technology made ‘obsolete and unnatural’ the old handcraft tradition of ‘laboriously joined’ structural parts; it compelled the artist to become the leader of an orchestra, where he was once a star performer’”. 2

This point of view freed the artisan to concentrate on the creative aspect of the work and relieve him or her from the drudgery of handcrafting each element of every article produced.

The onset of World War I finished off most workshops and any that remained were silenced by the Great Depression.

Art Nouveau 1880-1910

Image Courtesy of Bonhams.

Evolving alongside the Arts and Crafts movement, the Art Nouveau aesthetic emerged separately with design differences and subtleties throughout Europe and America with a common goal – the elimination of the artistic status quo. There was a great deal of crossover with the Arts and Crafts movement and many of the same ideals and inspirational individuals and artisans could be claimed by both movements. Along with those ‘local’ influences, the style that was referred to as Japonisme began to integrate itself into design repertoires bringing a new look to artistic endeavors. Emblematic of the period were flowing lines, whiplash motifs, and the incorporation of traditional Japanese motifs such as bamboo, carp, wisteria, cherry blossoms, and water lilies. Nature dominated and botanical themes and entomological motifs proved inspirational along with the feminine form which swirled and undulated throughout.

Many notable French jewelers adopted the Art Nouveau look. Highly skilled, having come from the historical and traditional jewelry and decorative arts, these jewelers broke with convention and created amazing articles of fine jewelry. Feeling freed from the constraints of earlier jewelry styles, they incorporated unusual materials such as glass, wood, ivory, horn, tortoiseshell, enamel, metallic patinations, and a variety of colored gemstones in their work. Experimentation with these unique materials, using them in new and different ways, redefined prior interpretations of fine jewelry.

All good things must come to an end, and Art Nouveau surrendered itself to the next great idea. The functionality of a piece began to be the primary dictator of form. Art Nouveau was frivolous in that regard, not caring a wit about function, only about its magnificent form. Circa 1910 the energy gave out and the consumers moved on.

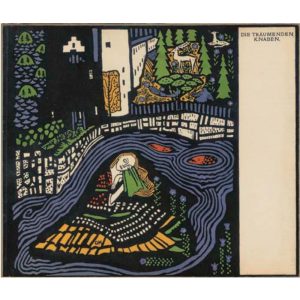

Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1933

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

An overwhelming Anglomania engulfed Austria at the fin de siècle. The Arts and Crafts publication “The Studio” was fueling a movement toward all things English. The Museum fur Kunst und Gewerbe (Museum of Art and Industry) in Vienna, modelled on the Kensington Museum in London (now the Victoria & Albert) held an exhibition to give an inspirational nudge to the local artisans. The Kunstgewerbeschule (Academy of Applied Art), located at the museum, provided an arts education to many of the future leaders and members of the Vienna Secession and the Wiener Werkstätte. A new publication from the Vienna Secession, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring) claimed in its mission statement that they were “steering the blustering spring gale of the new art on the continent through the dense grove of Austrian art” in its first issue 3to dispel the notion that Vienna was an extension of Germany.

The early adopters of the modern movement emulated the work coming out of England and Scotland and ignored the whiplash curves coming out of France and Belgium. Intrigued by the work of Ashbee and Mackintosh, Wiener Werkstätte principals Josef Hofmann and Koloman Moser traveled to England and Scotland to see their workshops in action. Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft was particularly inspirational and they returned to Vienna eager to create a cooperative workshop in the manner of Ashbee’s. Hoffman was seeking a Viennese version of modernism that was even more stark with simplified shapes and a rejection of symbolism so present in Mackintosh’s designs. His rigid architectural logic blended well with Moser’s many craft skills and his experience with commercial art. Eventually, Hoffmann’s Austere style evolved, through the influence of artisans such as Otto Czeschka and Dagobert Peche in the workshop, to a more eclectic and romantic style.

The war years left Austria in survival mode and demand for the decorative arts fell off. Renewed post-war interest took some time to build. Circa 1922, when demand reached pre-war levels, they opened a showroom in New York and exhibited at the 1925 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Unfortunately, the momentum could not be maintained, quality declined and design suffered. The firm closed in 1932. 4

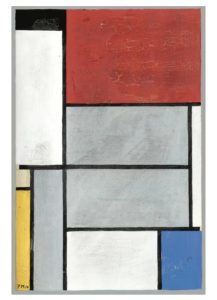

De Stijl 1917-1928

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

World War I forced the artist Piet Mondrian to leave his beloved Paris and seek refuge in neutral Holland for the duration. His mingling with the artists and architects there who shared common philosophies about art and society acted as a catalyst for the formation of De Stijl (The Style). Its members truly believed that their way was THE way to achieve social reform through the fusion of art and life.5 Never really meeting in person, De Stijl relied on its monthly eponymous magazine to communicate everything from opinions to accomplishments.

The predominant concern of the group was the harmonious creation of interior space which evolved over the life of the movement in 3 phases:

- 1917-1921 Architect dominance, where all decorative decisions were specified by the architect, and all others followed without creative input.

- 1921-1925 Painters began to have a greater impact on projects, and collaboration was at its peak.

- 1925-1931 Eventually the value of collaboration was discounted and each rejected the influence of the other.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Mondrian’s color theory became the group’s basic means of expression. Completely excluding nature and the world from any design consideration, a geometric aesthetic remained. Van Doesburg explained Mondrian’s neoplastic credo in the second issue of De Stijl:

The modern artist does not deny nature… but he does not imitate. He does not portray it. He creates a different image of it. He uses it and reduces it to its elemental forms, colors and proportions in order to achieve a new image. The new image is the work of art.6

Bauhaus 1919-1933

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Founded by Walter Gropius in 1919 in Weimar, Germany. The institute focused on teaching materials, form and color through the use of abstract exercises. The Bauhaus goal was “dedication to the unity of the arts with the crafts.” 7Its derivation from earlier movements, notably the Deutscher Werkbund which had exploited the ideology of the Arts & Crafts movement is evident.

According to the late German-American art and architecture critic, Wolf von Eckhardt

[Bauhaus] created the patterns and set the standards of present-day industrial design; it helped to invent modern architecture; it altered the look of everything from the chair you are sitting in to the page you are reading now.8

To turn the Bauhaus philosophy into reality, the school set three major goals for its participants. The primary goal for the school: to blend all the arts into a collaboration so that buildings and their contents could be constructed using all their skills in combination. The second was to elevate the crafts to the level of fine arts and to consider craftsmen to be artisans. Third, to stay in contact with industrial leaders and the leaders of the crafts movements in order not to create in isolation. To that end, students were trained in every subject by two masters one to teach theory and one to teach the application of that theory.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

As students were trained and completed their studies, some of them joined the faculty and the duality of their education eliminated the need for separate training in fine arts and craftsmanship. At around this same time, the school moved to an industrial city, Dessau, where the students and teachers built their own building and designed its contents.

Perhaps the most important contribution of the Bauhaus was the spread of their philosophy and artistic ideals throughout the world. In 1933 (having moved to Berlin in 1932) they were shut down by the police and stormtroopers of the new government. Staff and students scattered across the globe popping up in the United States, England, Hungary, the Netherlands, Japan, and Switzerland bringing with them modernist changes to the arts. Bauhaus with the credo of “Form follows Function” laid the foundation for the modernist movement from the 1940s-1960s.

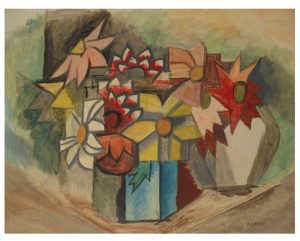

Concurrent Artistic Movements

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

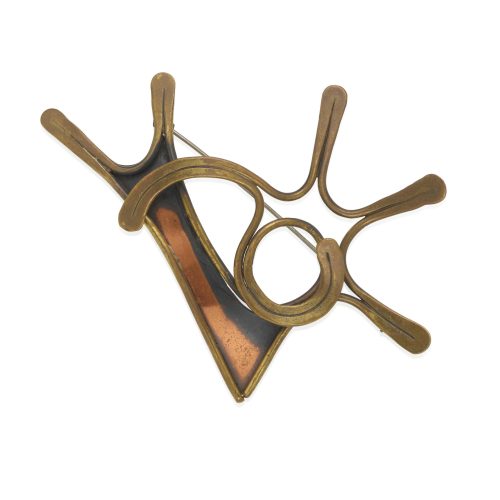

Other movements in the art world that contributed to the Modernist Movement included the Constructivist Movement (c.1915-1920s). This Russian abstract art and design period was initiated following the Russian Revolution and was allowed to continue there until it displeased the Soviet government c. 1920s. Upon its dissolution, the founders of this movement fled to Europe and the United States.

Constructivists believed it was necessary to use varied and various materials to create their artwork. The effect of this school of thought on jewelers was to cause jewelry to be hand assembled, with the inclusion of the use of positive and/or negative space, the incorporation of kineticism, and the use of precise geometry including intersecting lines and shapes. 9

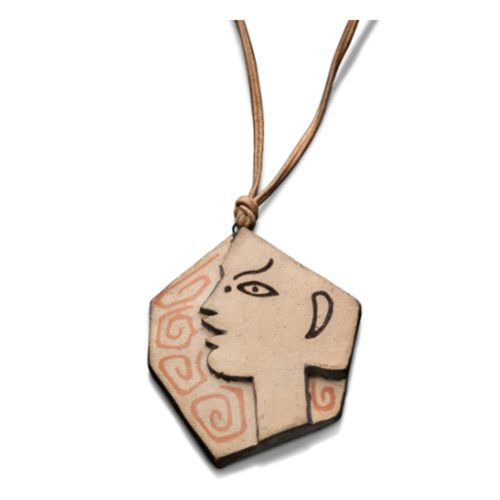

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Cubism (1907-1914) had a dramatic influence as well. Taking the fragmentation of objects from the canvas to a three-dimensional jewelry item and liberally applying symbolism to the work resulted in a throwback look evocative of African masks and pre-Columbian and Native American artworks.

Dadaism (c.1916-c.mid 1920s) espoused a philosophy that “Everything that the artist spits is art.”10 The use of found objects, which were viewed as having “artistic qualities” and techniques such as collage and montage were prevalent in Dadaism.

Surrealism followed bringing with it different contours and aspects of biomorphism with amoeba-like shapes and humanoid figurals.

Art Deco 1920-1940

Photo Courtesy of Bonhams.

Art Deco was the culmination of the art and design rebellions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its inspiration stretched from the ancient Egyptians to the as-yet-unrealized Space Age and everything in between. Geometry, streamlined aerodynamics, ancient patterns, Cubism, Constructivism, Abstraction, and more were fair game during the Art Deco Period. It has been postulated that, in reality, Art Deco started before World War I and continued after the war until the onset of World War II.

…Art Deco was the catch-all style of the interwar years, but one that had no precise beginning or end, as it was conceived before the Great War and lingered on (in architecture) into the 1940s. Described variously at the time as Moderne, Modern or the style of the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenites, and the “Flapper”, Art Deco took its present abbreviated name in the 1960s from the title of a book on the era’s foremost exhibition, L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, staged in Paris in 1925. 11

Two salons, La Societe des Artistes Decorateurs and Salon d’Automne, were the primary sources for the modernists to gain attention from the media and potential customers. Oddly enough, the interior decorations created for the luxury ocean liners following World War I provided an excellent international canvas in which to display the new ideas being put forth by these innovators. Art Deco became an extension of the new preoccupation with beauty and craftsmanship espoused by the earlier movements (sidelined by this new aesthetic). Decoration was the raison d’etre for this continuation of the importance of good design without excessive fussiness. Drawing on the movements that had come before, Art Deco was the culmination of the original thought and style they spawned.

Jewelers of this era did not confine themselves to wearable art, many crossed over into silversmithing, poster art, and other decorative endeavors. Lacquer, a crossover technique that flowed into Europe on the wave of Japonisme, was explored and employed with great fervor. Pure white, was unachievable with the traditional dyes used for lacquer, so eggshell mosaic offered a substitution when white was required. Glass was another material to appear in jewelry prior to Art Deco. Its pioneers, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and Galle so popular during Art Nouveau, fell off and Lalique continued to experiment and refine his techniques to great success, with mellower hues to meet the Art Deco sensibilities.

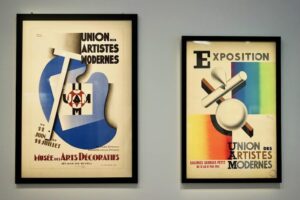

Credit: The Good Old Dayz 7.

The Union des Artistes Modernes was established in France on May 15, 1929. The exhibitions held by the UAM blended the artistic disciplines of jewelers, silversmiths, poster artists, typographers, architects and interior designers. A melding of the designs and innovations of this diverse group of artistic disciplines resulted in a cross-pollination of ideas and a radical new look to the end products of each. The forms employed in the work of these artists were moving from the geometric aesthetic of Art Deco to a more sinuous abstract contour. Designers like Jean Desprès took inspiration from the shapes and forms of machinery, engine parts in particular.12

Not only were they artists, but they were also theoreticians expressing their beliefs in writing to convince the skeptics of their point of view. While this was a groundbreaking unification of diverse artists under one umbrella, the synergism was short-lived and the group dissolved as the winds of war began to blow through Europe.13

With Art Deco, creative impetus moved from handmade and guild collaboration to functionalism demanding new materials, and mass production to meet the demand for fabulous design for the masses.

Streamlining c.1920s-c.1930s

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

The skyscraper became the most visible and durable language of modernism with reflections of its structure seen in many everyday objects. Accessories designers used this terraced form to inspire their creations. This began in the 1920s and ended with the onset of the Great Depression. Capitalism as design imagery became passe and a look toward the future with everything streamlined became the overwhelming aesthetic employed by designers.

Handcrafting, already on the decline, now became altogether too expensive. Simplicity and standardization were the keynotes of the new Modernism. American designers concentrated on the production of machine-made articles in quantity, at reasonable price, which would still meet a high aesthetic standard. An old adage was recalled, “it is what is left out that makes a work of art”. The machine, for so long a silent partner in all this was venerated in the exhibition “Machine Art” held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1934. 14

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Creeping into the design for everything from trains and automobiles to teapots and toasters, everything was being streamlined. In jewelry, the streamlined machine age can be spotted in the form and function of the Art Deco artist designs and Retro Era creations. The MoMA Machine Art exhibit featured machines, parts, household and office equipment, kitchenware, scientific instruments, and laboratory glass and porcelain displayed as art.

Besides the French decorative movement in the ’20s there developed in America a desire for “styling” objects for advertising. Styling a commercial object gives it more “eye-appeal” and therefore helps sales. Principles such as “streamlining” often receive homage out of all proportion to their applicability.15

The onset of World War II knocked streamlining out of fashion as machines were no longer romanticized as beautiful designs but as destructive instruments of war. Remaining were amorphous shapes and undulating lines which would re-emerge post-war in the work of studio jewelers and modernist design.

Retro c.1930s-c.1940s

Elements of the Streamlined aesthetic applied to a machine-age look emerged in the shiny bold jewelry we now call Retro. Jewelry from the period had a highly polished finish, clasps, hinges, and findings that evoked machinery, colorful gold and bold gemstones. Necklaces that resembled gas pipes or tank track-styled heavy-duty chains and bracelets with rolled and scrolled pipe-like elements predominated. Some of the severe geometry of Art Deco survived but was often smoothed and polished to a high finish, set with a large colorful gemstone (often with a geometric cut) instead of paved with many smaller stones.

Convertible jewelry, essentially small, but elegant works of engineering was popular. Clips worn on a dress could be added to a bracelet or necklace for a different look. Necklaces could be shortened and bracelets lengthened due to the precision machining of tiny parts. Gold (often with a rose or green hue) was the primary metal used during this time due to wartime restrictions on platinum.

The conclusion of World War II, with its inherent renewed availability of metals and gemstones, led to the gentle morphing from severe retro styles to the softer more amorphous modernist motifs.

Post World War II and Studio Jewelers

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

What began as a rebellion in the 1930s, began to thrive in its own right in post-war America. With the change in the political climate leading up to World War II, many of the leaders and innovators of the various art movements in Europe emigrated to the United States. Bringing their fresh ideas and varied teaching philosophies to a whole new audience, many secured teaching positions in art schools and college art programs.

Studio jewelers, rejecting the intrinsic value aspect of jewelry creations embraced the teachings of those earlier movements and created works that drew their “value” from their artistic merit, not the costliness of the materials.

Contemporary art became more expressive and less literal. The machine-age faded away and everything became more organic. Everyday objects took on a more biomorphic, organic, abstract design. Colors were vibrant and were applied to everything from the mundane to the magnificent. Kinetic elements were featured in jewelry design. Sculptural, dimensional wearable art resulted from this fusion of art and design. All of the varied art movements that preceded left their imprint in the designs of the studio jewelers.

In 1946 The Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibit of “Modern Handmade Jewelry” featuring both “artist as jeweler” and “jeweler as artist.” This marked the beginning of a “wearable art” movement in America. Studio jewelers were featured along with non-jeweler “box office” artists. This blending of artists and studio jewelers created an equal footing for applied and fine arts. 16

The New York Times reported on the Exhibit as follows:

MODERN JEWELRY SHOWN

Museum Displays the Creations of Craftsmen-Designers

The Museum of Modern Art opened yesterday an exhibition of modern handmade jewelry by craftsmen-designers, some of whom are also painters and sculptors.

Necklaces and bracelets by Izabel M. Coles are made of safety pins enameled in blues and greens and gold and silver colors. Creations employing washers, screws and other material found in a hardware store are shown by Anni Albers and Alex Reed of Black Mountain College, North Carolina.

Much of the jewelry is massive. A necklace by Alexander employs twisted wires that balance colored marbles.

Ellis Simpson, who made plastic eyes in an Army hospital, uses plastic for bracelets set with clusters of uncut crystal.

Julian Levy achieves a similar effect by hammering silver pieces in concave patterns.17

In 1948 a traveling exhibition entitled “Modern Jewelry Under Fifty Dollars” was curated by the Walker Art Center and sponsored by the Everyday Art Gallery under the direction of Hilda Reiss. The more sculptural jewels coming from the studio jewelers consisted of design elements not tied to the natural world or previous iterations of jewelry styles. Nothing was off limits and metals included non-precious alongside precious metals. Glass, plastic, ceramic, wood, bone, shells, rocks, and gems added color to the work. Personal adornment was the goal not an outright display of wealth.

Physical therapy for veterans of World War II also played a role in the perpetuation of studio or artisan jewelry. Jewelry and metalsmithing were the most popular of the crafts taught in GI Bill college courses. These newly minted studio jewelers went on to teach the craft to the next generation and inspired a world view for jewelry as art.

Reflecting on her career development c.1952 studio jeweler, Margaret De Patta noted:

The field of jewelry has gone through the same repudiation of old forms, re-examination of function and exploration of its physical materials as have all other creative fields since the rebellion of the Futurists and Cubists. The throwing overboard of traditional forms has opened up the entire world of creative exploration in materials, technics [sic], and contemporary concepts.18

Many studio jewelers continue to create their wearable art, rejecting mass production and repetition, as the traditional jewelry world runs in parallel.

Not immune to the artistic influences and movements that sparked the work of the studio jewelers, there was a lasting design impact on the conventional jewelry world. The jewelry we tag with the moniker “Mid-Century Modern” or “60s” jewelry is also the culmination of the previous hundred years of revolutionary art movements. While attempting to break away from the status quo and devise new rules for the creation and appreciation of art, these innovators changed the way we view our world forever.

Sources

- Duncan, Alastair. Modernism: Modernist Design 1880-1940. Minneapolis MN, Norwest Corporation. 1998.

- Machine Art: March 6 to April 30, 1934, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1934.

- “Museum Jewelry Shown.” New York Times, September 19, 1946: p33. Print.

- Preu, Nancy, Editor. Space, Light, Structure: The Jewelry of Margaret De Patta. Oakland, CA: Museum of Art and Design, 2012.

- Raulet, Sylvie. Art Deco Jewelry. New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1985.

- Schon, Marbeth. Modernist Jewelry 1930-1960: The Wearable Art Movement. Algen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2004.

- Schon, Marbeth. Form & Function: American Modernist Jewelry, 1940-1970. Algen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.,2008.

Notes

- Duncan, p.45, 47.↵

- Duncan, p.47.↵

- Duncan, p.111.↵

- Duncan, p.132.↵

- Duncan, p.136.↵

- Duncan, p.141.↵

- Schon (Modernist…) p.11.↵

- Duncan, p.157.↵

- Schon, p.13.↵

- Schon (Modernist…) p.17.↵

- Duncan, p.179.↵

- Roulet, p.172.↵

- Roulet, p.173.↵

- Duncan, p.229.↵

- Machine Art↵

- Schon (Modernist…) p.88.↵

- New York Times, p.33.↵

- Preu, p.19.↵