The era we now know as “Art Deco” received its moniker from the Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, held in Paris in 1925, which was largely dedicated to the jewelry arts. Emphasis was placed on the association of art and modern industry. Inspiration for this style was as far-reaching as Oriental, African and South American Art and as varied as Cubism and Fauvism, both popular movements at the time. The term “Cubism” was often used to describe jewelry of this era because of the angles, geometric lines and figurative representations used in its execution. A desire to eliminate the flowing lines of Art Nouveau and distill designs to their rudimentary geometric essence, thus eliminating seemingly unnecessary ornament, resulted in the cleaner and more rigid lines employed in Art Deco jewelry. A look forward toward modernism and the machine age also featured prominently at this juncture in jewelry history.

The First World War transformed women’s fashion like nothing in the preceding 100 years ever had. Taking up hard physical work in the absence of men required women to forgo their corsets, shorten their sleeves, cut their hair and raise their hemlines. When the war ended women were reluctant to return to their pre-war, constrictive garments, electing to follow instead the new fashions being presented by Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel. Simple, elegant clothing with straight lines and a freer silhouette required a rethinking of jewelry styles as well. All this fashion freedom allowed women to pursue sporting and leisure activities previously unavailable to them. Enjoying cocktails and cigarettes, wearing makeup, playing golf and tennis, driving, yachting and dancing till dawn were all a part of the new woman.

Other influences in the 1920s included the celebratory exuberance present throughout Europe, especially in France, following years of War. Previously shunned ideas, innovations and inventions were suddenly welcomed in the spirit of rebuilding and renewal. Money flowed more freely than it had during and even prior to the war. The Franc was losing value quickly and wealth in the form of jewelry seemed like a good idea to the newly prosperous post-war citizens. Magazines were widely circulated demonstrating what a woman should wear, how a home should be furnished and what to feel about nearly everything.

The exciting new archeological discoveries in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, primarily the tomb of Tutankhamun, influenced design motifs during this period. Figurative representations of lotus blossoms, pyramids, the eye of Horus, scarabs, nearly anything from the ancient time of the Pharaohs, was fair game as a jewelry motif. Notable jewelers working during this period adapted Egyptian influences into their designs and popularized them around the world. Entire scenes of ancient Egyptian life played out over bracelets, rendered in new color combinations created by combining lapis lazuli with gold and cornelian with turquoise.

The Indian jewelry that became so popular at the opening of the twentieth century was an inspiration to the jewelers of the 1920s both stylistically and chromatically. Carved gemstones, so popular in Indian jewelry, were utilized as flowers, leaves, fruit and other colorful accents. Design motifs were also drawn from Islamic art with their stylized forms and colorful accents. Persian motifs included flowers, plants, and arabesques rendered sumptuously in emerald and sapphire or jade and lapis lazuli. Chinese dragons and architectural motifs along with Oriental coral, pearls, and jade turned up extensively in Art Deco designs. Pre-Columbian design motifs from Central America and African tribal art often expressed as masks and ebony heads, all had some influence in this new aesthetic.

The two major schools of jewelry design were evident during this period. Bijoutiers-artistes emphasized design over intrinsic value. To that end they were using gemstones in a sculptural way, carving them into various geometric artworks using diamonds and other faceted gems as punctuation rather than the main focus. These works were often created with the collaboration of crafts persons who were not exclusively practicing the jewelry arts. Architects, painters, sculptors, an entire community of artists, shared ideas and designs, enriching each other’s disciplines and providing inspiration from an array of new sources. The new ways in which lines were used, color applied, relief employed, along with completely unrelated skills such as lacquer work came out of this new collaboration between artists.

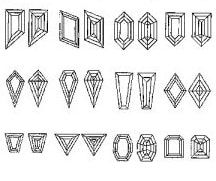

Bijoutiers-joailliers, working in the well-known Parisian jewelry establishments, were using calibré-cut precious gemstones to accent and enhance their geometric creations outlining designs and flanking rows of diamonds. As time went by they added trapeze, half-moon, triangle and other unusual diamond cuts to their repertoire. Their fascination with the Far East resulted not only in the use of fabulous carved gems from India, but in mixing precious stones with coral, rock crystal quartz, lapis lazuli, agate, and turquoise.

Each of the bijoutiers-joailliers had a slightly different view of the design influences of the times. Cartier reinterpreted their garland style in a more geometric form adding influences from the Far East, India, and Persia. Carved beads from India and mother-of-pearl plaques from China along with carved rubies, sapphires and emeralds found their way into their designs. The jewelry firm Mellerio inclined towards an Oriental influence in using carved gems in their creations.

Mauboussin used enamels and colored gems to provide strong contrast to vast fields of diamonds and used a circular or oval enclosure for their designs. Van Cleef & Arpels took a more Egyptian-influenced approach for their designs, using pharaonic motifs extensively. All the French jewelers were immersed in Art Deco design, but each interpreted and emphasized different design themes of the times.

The stock market crash of 1929 did not diminish the jewelry arts, in fact, it seemed to cause a revolution in both the size and scope of jewelry. The 1930s were characterized by large brooches, voluminous ear clips and wide bracelets lavishly rendered only in diamonds. Monochromatic creations featuring a wide variety of diamond cuts were the norm but color wasn’t completely left out, just relegated to the role of outlining or providing a framework for the featured diamonds. Convertible jewelry was a notable feature of pieces from the Art Deco period. Double clips that could be worn separately as dress clips, or jointly as a larger brooch were typical. Bandeaus broke up into matching bracelets, necklaces and brooches while earrings with detachable elements provided a day-to-night option.

Innovations

| Illustration | Innovation |

|---|---|

| Gem cutters learned how to achieve brilliance from faceted gems in new and innovative ways resulting in new cuts and shapes that could be arranged in mosaic-like designs. Various diamond cuts were arranged in patterns according to the radiance, luminosity and reflective qualities needed for the design. |

| The use of platinum in jewelry, with its great strength, required less metal to hold a gem securely, resulting in lighter, airier designs. A less expensive platinum substitute was developed in 1918 called osmior, plator or platinor which became popular with bijoutiers-artistes. |

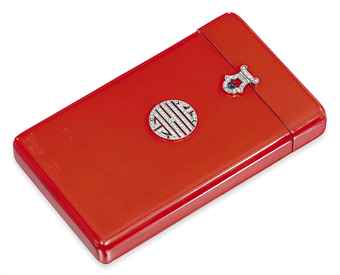

| Lacquer techniques from the Far East replaced the more expensive and labor intensive enameling so popular at the turn of the century. Chinese workers who had lacquered airplane propellers during the war were organized into studios to polish and lacquer jewelry and accessoires. |

| Perhaps the most important innovation was the mystery setting or serti invisible also known as the invisible setting developed by Van Cleef & Arpels which allowed gems to be mounted, through a system of grooves and rails, in such a way that no metal was visible. |

| A process whereby pearl-bearing oysters could be implanted with mother-of-pearl beads to produce cultured pearls, created enough of these gems that they became the iconic jewel of the 1920’s. |

| A plethora of plastic and other synthetic materials, most notably Bakelite, used to imitate gemstones, bone, wood, amber and other “natural” materials became widely available. |

Jewelry Overview

| Image | Description |

|---|---|

| Earrings Geometrically shaped earrings were now long and feminine, dangling from ear lobes exposed by the new shorter hairstyles, and were complimentary to the fashion for short, straight, drop waist, low-cut dresses. Earring designs were usually linear and set with diamonds, terminating to a featured, larger colored gem. The later 1920’s debuted more elaborate monochromatic earrings which highlighted multiple diamond cuts and were often convertible to brooches. During the 1930’s earrings seemed to curl up, spiraling right back up onto the earlobe. Shells, scrolls, leaves, and flowers, much larger in size than earlier earrings, clipped onto the lobe and hugged close to the face. |

| Necklaces Extremely long sautoirs were the iconic necklace in the 1920s and often featured a tassel or geometric pendant. Long strands of beads and pearls were knotted carelessly around the neck and worn down the front or back to punctuate the styling of the dress. Pearl necklaces, complementary to the wearer’s skin, were considered appropriate for day and evening wear. Shorter necklaces often featured gemstone beads or alternating diamonds and carved gemstones, terminating in a plaque shaped pendant, often detachable for use as a brooch or bangle decoration. Multi-strand graduated pearl or gem bead necklaces with diamond or gem plaques on either side created a festoon effect. Magnificent bib necklaces featuring large rubies, sapphires, emeralds, and diamonds replaced the simple diamond riviere. |

| Pendants Pendants, constructed in a wide variety of geometric shapes, were probably the quintessential Art Deco jewelry item. The bijoutiers-joailliers created elongated geometric shapes covered in diamonds and colored stones, featuring zigzag and step motifs along with influences of Chinese, Egyptian and Indian cultures. Tassels and fringe often swung from the bottom of pendants from this period. These sensational pendants dangled from chains (that featured pearls and gemstones) or from silk cords, at a variety of lengths directly complimenting the short tubular dresses. |

| Rings Larger more massive rings were the style of the day with platforms and planes decorated by a myriad of gemstones. They often centered a colored stone cut en cabochon, or a large diamond, surrounded by a border of smaller diamonds. Large emerald cut diamond rings and extreme step cut colored stones, such as emerald and aquamarine, were popularized during the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. Alternative materials such as ivory and rock crystal, from which to fashion a shank, were popular and were often gem-set, frosted and carved. Bands set all around with rubies, diamonds, sapphires, and emeralds were often stacked or rings with hinged half hoops designed to look like triple bands, were worn in their stead. The Cartier “Rolling Ring” was first made during this period and endures in popularity today. |

| Bracelets Starting out as narrow geometric links set with gems and colored stones in a definite pattern, the evolution of the bracelet would take it to wide pictorial straps. These wider strap bracelets could feature a whole story told in Egyptian symbols or an entire garden rendered in carved gems. Narrower bangles could be worn in quantity jingling all the way up the arm along with carved gemstone circular bracelets. Charm bracelets featuring exquisitely rendered remembrances or novelty pendants were revered for their movement and pizzazz. Cuff bracelets, armillas and stylized manchettes were popular again. Eventually, wide bangles became an alternate place to display the ever-versatile clip brooch. As the 1930’s progressed so did the size of the bracelets. Large diamond and/or gem set plaques hinged together with impressive pavéd oversized links took on new, even wider proportions. |

| Brooches and Pins Brooches were pinned on every conceivable article of clothing including hats. Carved rock crystal quartz circles designed in a buckle-like style or carved crystal scrolls were flanked and decorated by diamond-set plaques. Coral, onyx, and jade were also employed in a similar manner. Asian motifs were often adapted for brooches including pagodas, temples, columns, and the like, along with stylized flower and fruit baskets and fountains. Jabot or sûreté pins, styled similarly to a stickpin, featured decorative elements at both ends of the pin. Small geometric openwork plaques, ribbons, bows, novelty, and sporting brooches all continued to be in fashion. During the 1930s the clip brooch came into its own. Worn in pairs, one on either side of a dress, they could often be joined by the use of a brooch frame into one larger brooch. Usually, they were symmetrical or identical, but asymmetrical designs were available as well. Late in the period, hairstyling became relaxed and often quite large, serving as a precursor to the big jewelry of the 1940s. |

| Watches Newly miniaturized, watches were designed much like bracelets and existed in a great many different sizes, shapes and styles. Moiré or leather straps were the fashion for those participating in a sporting activity or to accessorize more relaxed daywear. In the evening watches had to compete for space on the arm with bracelets. As such, they were set with all manner of diamonds, colored stones and pearls, sometimes concealed under a cover within a larger bracelet or designed with a microscopic dial and completed by a petite bracelet all its own. Diamonds not only adorned the watch case and bracelet but often served as the watch crystal itself. Pendant or chatelaine watches were popular for a short time between 1925 and 1930 and fanciful brooches also were designed to conceal a tiny watch. Watches were added to cigarette cases, compacts, lipstick cases, and lighters. A new style of pocket or purse watch was designed as a covered rectangle that opened to reveal the dial as the two sides were pulled apart. The opening motion also served to wind the watch and when open the watch transformed into a desk or bedside clock. |

| Accessoire The minaudiere, compact, evening bag, lipstick, and cigarette case were must have accessories for the “modern” woman. Geometric patterns decorated the outside of these practical bits of fashion. Gemstones; carved, en cabochon, faceted and slabbed, adorned the exterior of boxes and compacts. Enamel and lacquer designs created fields of color to decorate the otherwise bland rectangular, round or octagonal receptacles. Bejeweled and enameled precious metal frames adorned purses and clutch bags. Cigarettes dangled from long gold and gemstone cigarette holders. |

| Hair Ornaments Early in the period, combs, used to support heavier longer hair, were no longer a necessity and hatpins, not needed on the smaller cloche style hats, all but disappeared. In the 1920s the tiara was replaced by the bandeau which was worn low on the forehead providing the perfect framing to the new shorter hairstyles. Adapted to the Art Deco style, they were designed with honeycomb patterns, lozenge shapes, and other geometric motifs and were often convertible to bracelets, brooches, necklaces, or clips when not in use as a bandeau. The exception to this style was found in England where court etiquette still dictated the wearing of tiaras for important state functions. Tiaras were thus produced with Art Deco styling for use on such occasions. Late in the period, tiaras re-emerged with wider popularity and a new heavier more substantial look to compliment the new longer hairstyles. Hair clips, combs, and aigrettes also returned showing new versatility in their convertibility to brooches. |

Shop at Lang

Fine Art Deco Lozenge-Cut Diamond and Sapphire Bracelet

This ultra-fine and fabulous Art Deco bracelet, dating back to the zenith of the Art Deco period, circa 1925, has all the earmarks of being by Tiffany & Company…

SHOP AT LANG

Art Deco 1.05 Carat Diamond Starburst Ring

This blazing sunburst for your finger centers on a beautiful, bright and shining bezel-set European-cut diamond. The scintillating stone, weighing 1.05 carats,…

SHOP AT LANG

Art Deco Diamond Dangle Earrings

Elegant diamond-frosted twists cascade from lever backs accented with a round brilliant-cut diamond, and wrap around two dangling crisply sparkling round brilli…

SHOP AT LANG

Video

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Cartlidge, Barbara. Twentieth-Century Jewelry: New York, NY: Harry N. Abras, Inc., 1985.

- Raulet, Sylvie. Art Deco Jewelry: New York, NY: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. 1989.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.