In a distinctive departure from the Industrial Revolution in Europe, the guild revival movement, known as Arts & Crafts, breathed new life into the business of designing and making jewelry. Suddenly, out from under the drab and lackluster tradition of mourning jewelry, a riot of enameled color, glimmering cabochons, and sinuous design gripped the imaginations of a particularly ambitious group of artistically minded individuals. A return to the past (and to the Far East) for inspiration and technique pushed artisans and designers headlong into a future that would forever alter our sense of pleasing design and true beauty.

The Arts & Crafts Movement evolved through a complex series of historical events all converging during the second half of the nineteenth century. Great enthusiasm had been shown for mechanization in industry during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Surprisingly, this over-mechanization was actually encouraged by the Royal Society of Arts through their awarding of prizes to inventors and innovators alongside those traditionally only awarded to artists. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was critiqued as having nothing to show of artistic merit, displaying virtually all machine-made items, thus providing proof that mechanization had resulted in a downturn of aesthetics in general design.

It was this Exhibition, along with the writings of John Ruskin and Owen Jones that planted the seeds of the Arts & Crafts Movement. Ruskin was a follower of the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to nature, primarily writing about art he eventually published a series of essays Unto this Last concerning social reform and the dehumanization of workers through the division of labor.

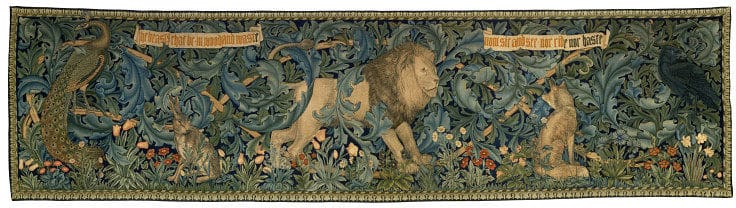

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Arguably, the chief aim of the Craft Revival was:

…to bring the pleasure of original creative activity into the lives of the men and women of the working classes, and to relieve the monotony to which repetitive mechanical labour condemned them for the greater part of their waking hours.1

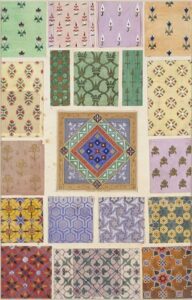

The publication of another book, entitled Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones, featuring stylized foliate designs derived from Medieval sources, extensively influenced design at the end of the nineteenth century. All this provided inspiration to a young William Morris who, having the financial backing of family money, was able to alter his life plan from one of service to the Church to the study of architecture which evolved into designing patterns for textiles, wallpapers and the like. Morris became the embodiment of the Arts & Crafts ideal of a return to nature and individual craftsmanship as a way to provide art and beauty into every home.

The founding of Morris and Company in 1861 (as Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., just in time to exhibit for the first time, in company with the Japanese and the Roman goldsmith Castellani, at the 1862 Exhibition, which could thus claim, on these grounds alone, to be the origin of the Art Nouveau movement in Europe and America) provided the example which was to inspire a number of other apparently uncommercial ventures, and to remove the monopoly in supplying the public from the mass-manufacturers whose taste was already being called into question by an increasingly critical and influential section of the consumer population.2

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Vocal advocates like William Morris, who believed that a piece should be produced from beginning to end by a single artisan, and John Ruskin, ever an advocate for the artisan, were relentless in their push toward a Medieval style of guilds to produce, by hand with good design elements, items used in everyday life. Gothic and Renaissance revival movements in jewelry turned the discerning eye to the past for pleasing shapes and motifs. With the guidance of Morris and Ruskin, a back-to-nature styling that relied heavily on floral and foliate motifs along with insects, shells and other objects from nature emerged like a breath of fresh air after the overriding Victorian mourning motifs.

Following the exhibition of 1862, Japanese decorative objects became extremely desirable. Japanese design influence, as well as their innovative use of mixed metals, began to seep into jewelry design. This perfect storm of change, revival and discovery led not only to the Arts & Crafts Movement but also to the overlapping Art Nouveau, Edwardian and Belle Epoque aesthetics, not only coincidental in time but in various design elements, techniques, and materials.

The Arts & Crafts Movement relied heavily on a guild-style education and employment of craftspeople who could then execute patterns provided by their designers. Ruskin opened the first in 1871, the Guild of St. George. Ruskin’s theories were the basis for organization and for the evolving guild and craft revival. Art schools and design schools were returning to the past for technique and design ideas.

Along with Morris and Ruskin, the Movement was led by a number of charismatic designers, many of whom, interestingly enough, began their careers as architects. This connection and commonality of training provided a conduit for the exchange of information, ideas and designs. C.R. Ashbee was one of the early architects/proponents of Arts & Crafts jewelry design. He translated Cellini’s Notebooks and used the techniques found within to train the guildsmen at his Guild of Handicraft. His model came to be the standard applied to the set-up of a successful Guild revolving around jewelry design and production. Ashbee was its principal designer and the guild members worked to produce his designs using the techniques espoused by the Movement. Ashbee’s influence can be seen throughout the work of many Arts & Crafts Guilds and artisans. The Birmingham Guild, also specializing in jewelry, The Viennese workshops, as well as Wiener Werkstätte, were all imitators of Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Collection.

Other guilds, such as the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Art employed workers who were not guild members, spreading work around to qualified artisans. Small workshops, art schools, and independent designers were also a big part of the Arts & Crafts Movement. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, along with the traditional international Exhibitions provided a forum for displaying and advertising the work of the many guilds and individual craftspersons. It was not economically feasible for each guild or small workshop to have their own commercial venue, in order to compete with larger corporate interests, their work had to be displayed at exhibitions.

The rejection of any use of traditional jewelers and manufacturers was a requirement of the proponents of the guild systems. The theory held that this rejection would lead to handmade items of beauty that relied only on their design and not the intrinsic value of their component parts for their esteem. Specialization by crafts-persons went against the principles of the Movement, each piece was to be made by one person from beginning to end. All of these elements were aimed to keep costs affordable to the middle class. Indeed, the craftsmen even eschewed the use of precious stones and employed silver (found in abundance in the late nineteenth century), aluminum and copper as the basis for their creations. When gold was used it was usually only as a minor accent. A hammered texture was popular for its softer luster and its departure from smooth, shiny, machine-made counterparts. Baroque pearls, mother-of-pearl and odd “toothy” freshwater pearls were used often. Stones such as moonstone, turquoise, garnet, opal, and amethyst were usually cut en cabochon (Ruskin had an objection to faceted gems) and generally collet-set.

Hand-painted enamel as a decorative element was an important mechanism for separating the handmade from machine-made. The use of leaves was an often employed distinguishing design element. So unique was the variation of leaves used by different artisans, they can sometimes be interpreted as proof positive of the maker’s identity. Medieval and Renaissance styling were the overwhelming design motif with necklaces, pendants, clasps, and buckles the most popular and useful items produced.

Some of the Movement’s proponents did not adhere closely to the philosophy. Henry Wilson, a successful “Arts & Crafts” designer, was known to have used professional rather than guild members to produce his wares. John Paul Cooper, another successful craftsman, was trained by Wilson’s jewelers and used those skills to produce his own jewels in the Arts & Crafts style.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Employing a methodology whereby the craftsman executed all elements of a piece from design to creation and ultimately marketing, proved to be costly and often yielded poor results. The items thus intended for the masses were only affordable by the elite, aesthetically astute; the experiment which rejected all use of machinery was failing. It is also ironic to note that the average citizen had absolutely no interest in the movement or its products.

Some of the most successful firms actually used mechanized systems to produce jewelry designed by the most popular Arts & Crafts artisans resulting in a mass market success. Liberty & Co. was one of the most prevalent. Embracing the aesthetic but not the handcrafted idealism, Arthur Liberty adapted Arts & Crafts for mass production. High standards of production at Liberty ensured a wide customer base for their jewelry. Sometimes eliciting customer participation in the choice of enamels and gemstones, Liberty was guaranteed to be popular with the jewelry-buying public.

Liberty’s were by no means the only English firm to venture into the Arts and Crafts field, it is the scale of the operation in their case which is unusual. Few of the firms who imitated the idea in principle bothered to establish a team of designers even remotely comparable with that assembled by Arthur Liberty and John Llewellyn.3

Liberty astutely employed the considerable talents of designer Archibald Knox who, working in a Celtic aesthetic, managed to meld the popular revival styles with a more contemporary use of the quintessential Art Nouveau sweeping whiplash lines and sinuous motifs. For the most part, Liberty kept the identities of their designers secret (at the time,) but it is known that they worked with W.H. Haseler & Son (with whom they later merged,) Bernard Cuzner, Jessie King, and Arthur Gaskin.

The use of enamel was an important design element in the pieces produced by Liberty with popular results. A very recognizable Liberty design featured concave leaves with translucent enamel filler. Starting out as incredible use of color and design, eventually, the commercial need won over the craftsmen’s talent and the enamel work became a more basic use of a few blended colors, most notably blue and green.

The melding of Gothic and Renaissance Revival, Art Nouveau, and Edwardian styles all happening concurrently was not lost on Liberty. Designs for more delicate necklaces and pendants in a more Edwardian style were also produced by Liberty. These more ethereal pieces usually included the signature enamel and a mixture of small pearls along with festoons of delicate chains.

Murrle, Bennett & Company was another firm that capitalized on a mass-produced version of the Arts & Crafts style. They produced a good deal of jewelry with a great similarity to that marketed by Liberty, with whom they did a regular business. What sets them a bit apart from Liberty is the German influence within the company. The use of a factory in Pforzheim, which also produced jewelry for many prominent German firms, elicited a cross-over of marketing. Murrle, Bennett & Co. displayed these German designs alongside those of English origin.

Charles Horner was another English firm that was mass-producing jewelry in the Arts & Crafts/Art Nouveau style, with one difference – The firm’s name was associated with the entire process. The manufacturing was not farmed out to other facilities, Horner did all their own production, in-house, from design to finished jewelry. They were by far the most prolific of all the firms working in this style.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Another group that followed the aesthetic but not necessarily the philosophy of the Arts & Crafts Movement was the Glasgow School. C.R. Mackintosh and wife Margaret along with J. Herbert MacNair and his wife Frances created some of the most distinctive designs of the era, popular in most of Europe but not in England.

The pairing of married artisans highlights another phenomenon of the Arts & Crafts Movement: women had an integral part in designing, enameling, and handcrafting jewelry. This was the first time that women entered the jewelry industry in any number and they were overwhelmingly successful. It is interesting to note that this was the first time that the press covered their collaboration and acknowledged their exhibition contributions. Georgie Gaskin, working with her husband, Arthur, became a metalsmith in her own right and William Morris’ daughter May was also known to be an early producer of jewelry in the Arts & Crafts genre. Goldsmith Charlotte Newman apprenticed under John Brogden in the 1860s, a firm that produced archaeological-style jewelry. Upon the death of Brogden in 1885, Mrs. Newman employed many of his craftsmen in her own firm. Many other husband-and-wife colleagues were documented as such throughout the movement with no appreciable difference between them as to the style or subject of their work.

A newly burgeoning affluence, as a result of the Industrial Revolution, allowed women more leisure time and many took advantage of craft classes to learn jewelry making, among other pursuits. According to the author Elyse Zorn Karlin, in her article “With a Hammer in her Hand: Women and the British Arts and Crafts Movement” in the book Maker & Muse:

Socially conscious projects were acknowledged as acceptable pursuits for middle- and upper-class women. A number of them organized informal craft classes to benefit men and women who needed to find a way to make a living. The women who established these classes also entered into the world of jewelry making in this way, with some becoming competent jewelry artists in their own right through their exposure to jewelry instruction.4

In the United States, the Movement was heavily influenced by British designers. Ruskin’s ideas came across “the pond” as did artisans already working in the Arts & Crafts aesthetic. Arts & Crafts Societies sprung up in Boston, Upstate New York and Chicago and had a heavy concentration on jewelry. The Americans produced a more stylized version with a paler palette and more simplistic designs such as paper-clip chains and tee and loop clasps.

Arts & Crafts jewelry was generally very practical and less frivolous than its predecessors. Cloak clasps, belt buckles, and belts were produced in the style with enamel and gemstone highlights. Hair ornaments were more likely to be elaborately carved horn or ivory combs than diamond-studded tiaras. The few tiaras that were made in the Arts & Crafts style were naturalistic designs with enamel rather than precious gems. Very few earrings were produced at least in part because earrings were not prominently in vogue at the time. Necklaces were the most important adornment and they often consisted of chains that were swaged, looped and festooned suspending pendants with enamel and cabochon gem decoration. Plique-à-jour enamel plaques were worked into dog collars. Enameled insects, flowers, and leafy plants were a common motif for brooches. Bracelets often alternated medallist style plaques with chain links, ribbons and flowers. Carved metal stylized feminine motifs and wrap-around insects and plants clutched cabochons to form the few rings designed in the Style.

The movement waned in the pre-World War II era and the guild movement all but disappeared after the war. Individual artisans continued to work in the Arts & Crafts style adapting their work to the changing tastes and breaking new ground with a metamorphosis to the Modernist Movement. Independent jewelers, working in a handmade style using techniques taught during the height of the Arts & Crafts movement, have continued to produce popular jewelry without the support of guilds and societies dedicated to the idealistic revolt against machine-made

Related Reading

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery: Second Edition: Colchester, Essex, N.A.G. Press Ltd., 1987.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Egger, Gerhart. Generations of Jewelry: from the 15th through the 20th Century, West Chester, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. 1988.

- Gere, Charlotte and Munn, Geoffrey C. Artists’ Jewellery: Pre-Raphaelite to Arts and Crafts. Woodbridge, Suffolk England: Antique Collector’s Club, 1989.

- Karlin, Elyse Zorn. Jewelry & Metalwork in the Arts & Crafts Tradition. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Ltd. 1993.

- Karlin, Elyse Zorn, Editor. Maker & Muse: Women and Early Twentieth Century Art Jewelry. U.S.: The Monacelli Press, © 2015, The Richard H. Dreihause Museum.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.