In 1900, the world witnessed a grand display of Art Nouveau jewels, objects, and architecture at Paris’s Exposition Universelle. This article will attempt to create a snapshot of this special moment in design history as well as put the Exposition into its larger social and political context.

The Ethos of Art Nouveau

Throughout the nineteenth century, artists and jewelers held the past in great esteem. One after another, historical revivals swept through the design world. From the 1830s until the 1870s, ancient-style jewelry held the public’s full attention. Items like cameos enjoyed a renewed popularity and jewelers experimented with long-lost manufacturing techniques like granulation. Images of Roman and Greek gods, as well as ancient objects like amphorae, were ever-present as decorative motifs. During the mid-century, Louis XIV and XVI’s court fashions had their turn. In the 1860s-80s, the public turned to Renaissance jewelry, with its brightly colored enamel work, as the next new thing.

Around this time, new artistic movements that rejected historical styles began to grow, including the Art Nouveau movement. Art Nouveau proponents aimed to evoke the eternal and ever-present in human experience by focusing on nature, not human culture. However, unlike many of their Victorian predecessors, they were not concerned with replicating natural objects as faithfully as possible. Scientific classificatory schemes and recent biological studies were not the driving force behind their depictions of the natural world. Romanticism and fantasy were. Art Nouveau jewelers took natural objects and turned them into expressions of abstract ideas—Beauty, the Eternal, the Feminine, the Fantastic. The resulting jewels were tiny works of art.

These pieces were emphatically not modernist in spirit. In Art Nouveau, one finds no celebration of the new, of technology and its products. Rather, one finds a rejection of modern, mechanized techniques. The pieces are beautifully designed and the work is hand-wrought and intensive. Artists were deemed creators—a special role in an age where mass-produced goods and a strict division of labor tended to extinguish the one-on-one relationship between the producer and object produced. Many Art Nouveau jewelers had received intensive training in fine arts, before turning to jewelry.

The Exposition as a Political and Cultural Event

Planning began for the 1900 Paris Exposition in 1892. At this time, French expositions were a government affair, not a private one. Since the end of the eighteenth century, the state had sponsored regular exhibitions in Paris, mostly to showcase national industrial goods and fine arts. Throughout the years these national expositions steadily grew in size and ambition. In 1851, Britain changed the game by hosting a fantastically successful international exhibition. Artists, inventors, and manufacturers from all over the world were invited to display their wares, foreign dignitaries were asked to attend and exotic foods and peoples, the fruits of the British Empire, were put on display.

Not to be outdone and eager to showcase their industrial and cultural achievements at a grand party, other states followed suit. Each new exposition aimed to exceed the display of its predecessors. In France, international expositions were held in 1855, 1867, 1878, and 1889—roughly every eleven years. In 1892, rumors began to circulate that Germany planned to host an exposition in 1900. The rumors were apparently true and set off a fury among the French public and politicians who saw Germany as a usurper, wanting to rob France of its regularly scheduled international fête. The reaction, as historians describe it, was exacerbated by recent military and economic defeats at German hands.

As the historian Richard Mandell put it:

However much France saw her strength and glory slipping in other areas, there was one cultural manifestation in which French supremacy was unchallenged—the organization and staging of the universal expositions. For Frenchmen, by this time, thoughts of the expositions produced emotions remarkably similar to those aroused by thought of the French colonial empire. In the face of political embarrassment, humiliations in diplomacy, and economic stagnation, expositions and empire compensated somewhat for other defeat. Though hardly the creation of the Republic per se (the empire was forwarded by freebooting adventurers, the expositions by autonomous bureaucrats) both showed (or appeared to—the important matter) dynamic, richly inventive French Republic to the world.1

Eschewing a diplomatic solution to the conflict, the French government decreed that it, not Germany, would host an international exhibition in the year 1900. The Germans relented soon thereafter, and preparations for the exposition began.

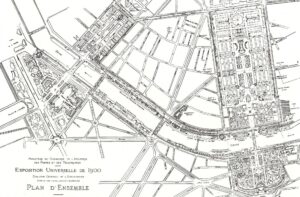

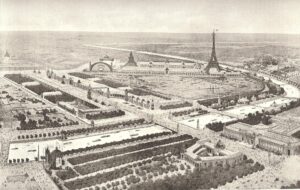

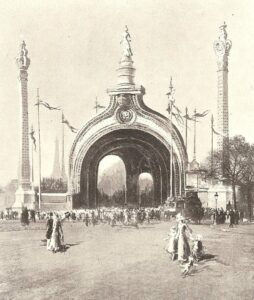

The event would become the largest-ever gathering of its kind.2 From April to November, just over fifty million guests filed through its gates. The grounds were over two-and-a-half miles long, spanning much of central Paris. Universelle referred both to the scope of the exposition’s exhibits and to the origin of its participants. Participants came from all over the world. Forty-seven nations accepted invitations. Of these, twenty-two had special pavilions along the Rue des Nations. There was also a medieval French village, populated with authentically costumed inhabitants. Exhibits covered all aspects of modern life: agriculture, consumer goods, machinery, new technologies, fine arts, decorative arts, theatre, dance (see appendix for a complete list).

Bicycles and automobiles were first introduced to the general public here. Other innovations included x-rays, sound-synchronized movies, and wireless telegraphs.3 There was also a sports competition in the Bois de Vincennes, which was considered “the second modern meeting of the revived Olympics”.4 National food and drink were available in restaurants located inside and outside the Exposition gates. Carnival rides were on offer for those who wanted them but the moving sidewalk, which crossed the Exposition grounds at varying speeds, was one of the greater novelties. Over a hundred conferences were held within and outside the Exposition grounds on a wide range of topics, including education, public health, international postal regulations, and photography. By all measures, the Exposition was an exciting, bustling affair.

Art Nouveau at the Paris Exposition

Art Nouveau found itself in a slightly awkward position during the Paris Exposition for several reasons. First, the exposition’s theme was “A Retrospective of the Previous Century.” Because of the 19th century’s historical focus, a retrospective would naturally draw attention to designs inspired by past ages. As mentioned earlier, history did not interest Art Nouveau jewelers. Second, the exposition was in large part, a celebration of technological progress and industrialization. Art Nouveau adherents tended to downplay the value of these developments and were, at the very least, ambivalent about the fruits of industrial progress as exemplified in mass-produced, consumer goods.

Despite these tensions, Art Nouveau artists were, in another sense, perfectly at home at the Paris Exposition. Theirs was the new wave in design. The movement possessed a sense of optimism and excitement. Their pieces were unusual, vibrant, and technically impressive; the definition of modern design. Artists from all around the globe used the event as a meeting point and proving ground, a place where they could garner international honors, awards, and attention.

At the Exposition, Art Nouveau artists exhibited on the Esplanade des Invalides, a broad walkway on the Seine’s right bank, which occupied the Exposition’s northwest corner (see map). Here one could see “lightly built though lavishly decorated buildings devoted to the broad classification of decorative arts. This included jewelry, costumes, ceramics, furniture, carpets, and all other aspects of interior design”.5 French decorative arts were housed on the west side of the Esplanade and foreign decorative arts were showcased, according to country, on the east side. Each nation chose its representatives carefully. Craftspeople and businesses eagerly competed for space within their respective national pavilions; reputations were made and lost at these great expositions.

Memorable displays of Art Nouveau jewels were found on either side of the Esplanade. René Lalique and Emile Gallé, both Frenchmen, were veritable stars of the show. Lalique created enameled objects and jewelry while Gallé crafted hand-blown glass objects. Samuel Bing’s luxurious seven-room pavilion on the French side also caused a stir. This was no surprise. Bing’s Paris shop, L’Art Nouveau—Maison Bing, was the namesake for the Art Nouveau movement; many of the movement’s artists got their break, or their inspiration, from him. On the Esplanade’s foreign side, Tiffany & Company also offered an impressive display. Their fame, as far as Art Nouveau is concerned, is largely due to the influence of Louis Comfort Tiffany. Tiffany earned notice by crafting incredible glass objects, especially lamps and he later became director of jewelry design at Tiffany & Co.. The German, Austrian, and Hungarian pavilions were also replete with Art Nouveau designs. As Mandell notes, “whole rooms in the new style were parts of the government pavilions. Some of these were created by artists whom Bing had first patronized in Paris but who had left Paris for an artistic climate more congenial to innovation.”6

While the Art Nouveau style was popular at the exhibition, it was not omnipresent. The majority of the art and architecture was not in the new style. Art Nouveau was being displayed just “in a few places”7 and it was overshadowed by the “follies of Beaux-Arts zeal”.8 Beaux-Arts here refers to a style of architecture and decoration taught at various French fine arts schools throughout the nineteenth century. Beaux-Arts adherents drew freely on various historical influences, earning their design sensibility a dubious title: “the opulent bastard of all styles.” In Mandell’s estimation, “little of enduring merit was actually accomplished in this great tournament of taste”.9 Art Nouveau, and Impressionism were the exceptions to the rule, and these were a peripheral presence.

The Effect of the Exposition on the Art Nouveau Movement

In one sense, the Exposition was the beginning of the end. With over fifty million people attending the Exposition, the movement’s artists gained a wide audience. One needn’t possess a crystal ball to see the effect: increased demand for the pieces, lowered manufacturing, and design standards, and a resultant faltering of the originality and artistic care central to the movement.

As historian Vivianne Becker puts it:

After 1900, the Art Nouveau jewel became high fashion and, as the motifs and themes were copied, often indiscriminately, the style became diluted, its initial force undermined. This popularization, ironically the aim of Art and Crafts exponents, finally led to the eclipse of the Art Nouveau jewel.10

By 1910, Art Nouveau had all but died. The Exposition of 1900 thereafter has been seen as the movement’s greatest moment and, at the same time, the start of a precipitous and unfortunate decline.

Related Reading

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Art Nouveau Jewelry. New York: Dutton, 1985.

- Harrison, Stephen and Emmanuel Ducamp, Jeannine Falino. Artistic Luxury: Fabergé, Tiffany, Lalique. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2008.

- Mandell, Richard D. Paris 1900. Toronto: the University of Toronto Press, 1967

- Morss, S.E. Report of Hon. S. E. Morss, Consul-General of U.S. at Paris, to Secretary of State. Paris: US government, 1896.

- Thompson, D. Croal. The Paris Exhibition: 1900. The Art Journal Office, H. Virtue Company Limited, 1902.

Appendix

Official Classification of Exhibits at Exposition (from Morss, Appendix): Classification:

Group No. 1-Education and Instruction

- 1) Infant, primary, and adult education.

- 2) Secondary Instruction.

- 3) Superior education, scientific instruments.

- 4) Special artistic education.

- 5) Special agricultural training.

- 6) Industrial and commercial training.

Group No. 2-Works of Art

- 7) Paintings, cartoons, designs.

- 8) Engraving, lithography.

- 9) Sculpture, medal, and gem engraving.

- 10) Architecture.

Group No. 3-Instruments and General Processes of Letters, Sciences, and Arts.

- 11) Typography, printing in general.

- 12) Photography in two categories, viz., professional, and amateur.

- 13) Books, musical editions, bookbinding, posters, newspapers.

- 14) Maps, instruments of geography and cosmography, topography.

- 15) Instruments of precision, coins, medals.

- 16) Medicine.

- 17) Surgery.

- 18) Theatrical plants, materials, and accessories.

Group No. 4-Materials and General Processes of Mechanics.

- 19) Steam engines.

- 20) Engines using other motive power (except electricity).

- 21) General mechanical apparatus.

- 22) Tools and implements of manufacturing.

Group No. 5-Electricity

- 23) Production and mechanical utilization of electricity.

- 24) Chemical electricity.

- 25) Electric lighting.

- 26) Telegraphy and telephones.

- 27) Different applications of electricity.

Group No. 6-Civil Engineering and Transportation

- 28) Materials and processes of civil engineering.

- 29) Models, plans, and designs of public works.

- 30) Coach and cart building.

- 31) Saddles and harnesses.

- 32) Railway and tramway construction.

- 33) Shipbuilding.

- 34) Aerostation.

Group No. 7-Agriculture

- 35) Agriculture.

- 36) Viticulture.

- 37) Agricultural Industries.

- 38) Agriculture, science, husbandry statistics.

- 39) Alimentary agricultural products of vegetable origin.

- 40) Alimentary agricultural products of animal origin.

- 41) Nonedicble agricultural products of animal origin.

- 42) Useful insects and their products, hurtful insects, and vegetable parasites.

Group No. 8-Horticulture and Aboriculture

- 43) Materials and processes of horticulture and arboriculture.

- 44) Kitchen-garden plants.

- 45) Fruit trees, fruits.

- 46) Trees, shrubs, plants, ornamental flowers.

- 47) Conservatory plants.

- 48) Horticultural and nursery seeds and slips.

Group No. 9-Forestry, the Chase, Fisheries, Cueillettes

- 49) Materials and processes of forestry.

- 50) Forestry products.

- 51) Sporting arms.

- 52) Products of the chase.

- 53) Fishing tackle and product, pisciculture.

- 54) Wild or non-cultivated vegetable products, implements used in gathering the same.

Group No. 10-Food Stuffs

- 55) Materials and processes of alimentary industries.

- 56) Farinaceous products and their derivatives.

- 57) Bread and pastry.

- 58) Preserved meats, fish, vegetables, and fruits.

- 59) Sugar, confectionery, condiments, stimulants.

- 60) Wines, spirits.

- 61) Miscellaneous beverages.

Group No. 11-Mines and Metallurgy

- 62) Materials and processes and products of mines, ores, and quarries.

- 63) Materials and processes and products of large metallurgy.

- 64) Materials and processes of small metallurgy.

Group No. 12-Decoration and Furniture of Public Buildings and Habitations.

- 65) Fixed ornamentation of public edifices and of dwelling houses.

- 66) Stained glass.

- 67) Wallpaper.

- 68) Low-grade and high-grade furniture.

- 69) Carpets, tapestries, and other upholstery fabrics.

- 70) Temporary decorations and upholstery products.

- 71) Pottery.

- 72) Crystal and glassware.

- 73) Heating and ventilating systems and apparatus.

- 74) Lighting apparatus other than electric.

Group No 13-Threads, Yarns, Textile Fabrics, Wearing Apparel.

- 75) Plants, materials, and processes of spinning and making rope.

- 76) Plants, materials, and processes of weaving.

- 77) Bleaching, dyeing, printing, and finishing of textiles, plants, materials, and processes.

- 78) Materials and processes of needlework, and the making of wearing apparel.

- 79) Cotton threads and fabrics.

- 80) Linen, hemp, etc. threads and tissues, rope products.

- 81) Woolen yarns and tissues.

- 82) Raw and manufactured silks.

- 83) Laces, embroideries, and trimmings.

- 84) Ready-made apparel for men, women, and children.

- 85) Miscellaneous attire.

Group 14-Chemical Industries

- 86) Chemical and pharmaceutical arts.

- 87) Paper making.

- 88) Hides and skins and leather.

- 89) Perfumery.

- 90) Tobacco and match manufactures.

Group 15-General Manufactures

- 91) Stationary.

- 92) Cutlery.

- 93) Gold and silver wares.

- 94) Jewelry.

- 95) Clocks, watches, and other timepieces.

- 96) Bronze, cast iron, and forged iron, embossed metals.

- 97) Brushes, notion, basketwork.

- 98) Rubber products, traveling, and camping articles.

- 99) Toys and games.

Group 16-Social Economy, Hygiene, Organized Charity.

- 100) Apprenticeship, protection of child labor.

- 101) Wages, profit sharing.

- 102) Wholesale and retail industries, cooperative associations or production, and credit.

- 103) Cultivation of large and small farms, agricultural syndicates, and banks.

- 104) Safety of workshops, labor regulations.

- 105) Workmen’s dwellings.

- 106) Cooperative stores.

- 107) Institutions for intellectual and moral development of workmen.

- 108) Saving banks, friendly societies.

- 109) Public and private efforts for improving the condition of the people.

- 110) Hygiene.

- 111) Public relief.

Group 17-Colonization

- 112) Modes of colonization.

- 113) Colonial plants and materials.

- 114) Special merchandise for exportation to colonies.

Group 18-Military and Naval.

- 115) Artillery armaments and plants.

- 116) Military engineering.

- 117) Naval engineering, hydraulics, torpedoes.

- 118) Maps, hydrography, sundry instruments.

- 119) Military and naval equipment and administration.

- 120) Hygiene and sanitary material and services.