As the long reign of the four Georges drew to an end, the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of York and Strathearn (son of George III) and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, ascended the throne. Alexandrina Victoria, the young princess, crowned Queen Victoria of England, wafted in like a fresh breeze across Britain and held her subjects in thrall until her death in 1901. The 63 years and 7 months of her reign became known as the Victorian Era, throughout which Queen Victoria influenced everything from politics to fashion to furniture to the mores of the day.

A time of great change in the world, the Victorian era ushered in such inventions as the automobile, electricity and indoor plumbing and spawned rapid changes in industry along with amazing scientific discoveries. Victoria’s reign coincided with a time when, spurred by the advent of photography, the phenomenon that would become mass media was putting down its roots. Women’s magazines featuring homemaking, motherhood and fashion were gaining popularity. The Illustrated London News made it their mission to “connect the cottage to the palace.”

The young Queen’s portrait was, quite literally, everywhere, rapidly becoming public property. The coronation and her marriage to Albert caused a frenzy in the portrait distribution business. Images were put on medallions, ribbons, in the papers, and portraits, suitable for framing, appeared in pull-out sections of periodicals. Never had anyone been so thoroughly followed and emulated. The Queen’s jewelry and fashion, along with that of her family and members of the court, influenced the world.

Jewelry was extremely important in the life of the Queen. As a girl, gifts of jewelry and accessories were abundant. These items were of the fashion of the time and not particularly notable but, held great sentimental value. Court life was lively and gay under the reign of the young Queen. She wore jewelry liberally and abundantly. The Crown Jewels and treasures from prior generations of royals were re-set and re-styled to suit the Queen. A sunray necklace from Queen Adelaide was worn often by Victoria as a diadem. A Royal portrait depicted her in George IV’s regal circlet with Queen Charlotte’s diamond earrings. Symbolically she wore a serpent bracelet to her First Council showing her aspirations for “the wisdom of the serpent”. This jewelry served as a dynastic continuity for the Crown.

While Victoria was now setting the fashion trends in dress and jewelry, the items she wore symbolically were not necessarily her personal favorites. A heart-shaped locket containing a lock of Prince Albert’s hair, a portrait miniature of Albert and a sapphire and diamond brooch he presented to her prior to their wedding were the jewels she treasured above all others. On her wedding day, she wore a simple wreath of orange blossoms on her head which became the iconic bridal headdress from that day forward.

Her bridal jewelry consisted of an elaborate “Turkish” diamond necklace and matching earrings, the sapphire and diamond brooch from Albert and the Order of the Garter. Victoria’s train bearers each received an eagle brooch paved in turquoise with a ruby eye and pearls in its claws designed by Albert. Six dozen rings with medalet bridal portraits in enamel were produced as mementos for friends and golden pencils adorned with enamel medalets were presented to the men.

Albert often bestowed Victoria with jewelry of his own design. An ongoing gift, which began as a gold and porcelain orange blossom brooch and later included earrings and a wreath, all in the orange blossom theme, not only became symbolically important in royal weddings, it was quite possibly the most copied of all of the Queen’s jewels. The proliferation of the Queen’s image through the new media allowed fashion trends to spread quickly around the world. Close examination of the portraits of the day reveals women copying Victoria’s jewelry and gowns almost exactly.

R & S Garrard.

Jewelry was produced in great quantities for the queen to wear to balls and entertainments, marking the birth of each of her nine children, birthdays and anniversaries, and as gifts to be presented at family marriages and births. Detailed records exist in the archives of the jewelers who produced them; R. & S. Garrard and Rundell, Bridge & Co. In addition, trained jewelers and artisans flooded into Britain as a result of unrest on the continent. Many of these fine artisans went to work producing jewels for the Crown.

In 1848 Victoria and Albert purchased Balmoral Estate in the Highlands of Scotland and built a family home there. Victoria was enchanted with Scottish design and she began collecting Scottish jewelry at their very first visit. Jewelry in the Scottish tradition was generally recognized as “fashion” jewelry. Flexible bracelets, enameled with family tartan colors, and brooches and pins were the most popular Scottish jewelry pieces. Although most of these items were silver, some were fashioned in gold. Scottish Victorian Jewelry contained smoky golden quartz from the Cairngorm Mountains, carnelian, bloodstone, jasper, moss agate and enamel.

Albert continued to be instrumental in the design of jewelry worn by the Queen. A sapphire and diamond diadem, designed to be worn in a number of ways, was a favorite of the Queen. Collecting suites of diamonds, Albert would arrange them into parures for the Queen. He even went so far as to have the Koh-i-Noor diamond re-cut. He further revived the “Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce”. Loaning items from the Royal Collection to various exhibitions he allowed the public a unique opportunity to view these treasures.

In 1851 Albert sponsored The Great Exhibition of Industry of All Nations, in London, thereby spawning the Age of International exhibitions. In addition to the wondrous machinery and inventions on display, Victorian jewelry, watches and precious stone exhibits attracted worldwide attention. More than 6 million guests visited the exhibit viewing the 280 carat Koh-i-Noor diamond and the 177 carat diamond belonging to Adrian Hope. Items of jewelry in commonplace use, like chatelaines and brooches, earrings, crosses, quatrefoils and necklaces were also on display. Jewelry reflecting a Gothic revival of medieval design, enameled architectural elements and natural motifs, such as gem-embellished flowers, were also exhibited. The varied and eclectic designs displayed here appealed to the romantic nature of the Victorians and became identifying motifs of Victorian Jewelry. Victoria and Albert each purchased a “keyless” watch by Patek & Co. at the exhibition, bringing a great deal of celebrity to the firm.

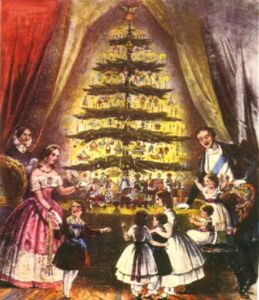

Albert’s Germanic roots were evidenced in the traditions and rituals that were established in the royal household. The way in which birthdays and Christmas were celebrated by the royal family became the norm throughout the realm. Silver, gold and diamond anniversaries and jubilees were celebrated in the German style. Year jewels and souvenir items commemorating exhibitions and festivals kept those in the jewelry arts quite busy during this era. Visits were exchanged in 1855 between the French Emperor and Empress, Napoléon III and Eugénie, first to London and later Victoria and Albert to Paris. An incredible amount of preparation of jewels, including re-setting and restyling, was done by Garrard in London and Bapst in Paris. The garments and jewels of the Queen and Empress were widely reported on. Jeweled gifts were exchanged and, undoubtedly, a great deal of attention was paid by each to the other thereby influencing style and design in both countries.

In 1858 the focus was on the nuptials of their eldest daughter, Vicky, and Prince Frederick William of Prussia. A wedding present from the groom included a pearl necklace composed of “32 large Oriental pearls”. To the companions of Princess Royale, the Prince presented a gold bracelet adorned by a diamond-set Prussian eagle. The Queen wore the crown jewels including the Koh-i-Noor. This wedding was designed to be the blueprint for all future royal marriages.

Next to be married was the Prince of Wales but, before he could be wed, fate intervened. In March of 1861 the Queen’s mother died, followed later that year by the death of Victoria’s beloved Albert. Victoria, and the entire country, was plunged into mourning. The royal jewelers were kept extremely busy by the production of the requisite mourning jewelry. Lockets with photo miniatures and hair remembrances were produced in volume for the Queen to distribute to relatives and friends, along with stickpins bearing the Prince’s portrait, and memorial pendants. A mourning period of three months was established for the court, but the Queen remained in mourning for the rest of her life and dress for the court followed suit.

Eventually, the Queen resumed traveling with limited public appearances. Her outfits were still composed of black silk but became increasingly elaborate with decorative black beads and other trims. Diamond jewelry worn in tremendous quantity adorned her widow’s weeds. At the 1887 Golden Jubilee, the Queen was resplendent with diamonds, wearing a large collet diamond necklace suspending the Lahore diamond as a pendant along with large diamond earrings, various badges and cameos. Souvenir pendants, brooches and medals were created in large volumes to celebrate the Golden Jubilee, and later the Diamond Jubilee, and many still exist today.

January 22, 1901, the Victorian era came to an end with the death of Britain’s beloved Queen. Displayed on her coffin were the small imperial crown, the collar of the Garter along with the regalia; two orbs and the scepter. Much of her jewelry had been secured as property of the Crown, held in trust for English Queens. Jewelry boxes of purple morocco lined with white velvet bearing the Queen’s cipher were created for the distribution of the remainder of her jewels. She was succeeded by her son, Edward VII.

Curious to Learn More About Queen Victoria?

In honor of the Diamond Jubilee celebrated in 2012 for Queen Elizabeth II, the Royal Archives has released an online version of the diaries of Queen Victoria. You can read them here: Queen Victoria’s Journals The diaries span the period from her childhood until just days prior to her death in 1901. A fascinating look at this era so rich in history.

Related Videos

More Victorian Jewelry

Shop at Lang

Victorian Antique Cushion Cut Diamond Pendant Necklace

This consummate Victorian pendant necklace, artfully and intricately designed and hand fabricated in silver over gold, sparkles front and center with a bright a…

SHOP AT LANG

English Victorian Five-Stone Diamond Carved Ring

Why have only one diamond on your ring when you can have five splendidly sparkling beauties all in a row. In this classic Victorian 'carved ring,' a quintet of…

SHOP AT LANG

Victorian Diamond Flower Clip Earrings

Magnifique! From the mid-to-late 19th century come these fabulous (and sizable) flower earrings that sparkle all around with petals packed to the hilt with 3.85…

SHOP AT LANG

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery: Second Edition: Colchester, Essex, N.A.G. Press Ltd., 1987.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.