Technique

Photo Courtesy of Pierotucci.com.

Micromosaics are a type of mosaic created from tiny fragments of glass, called tesserae. The tesserae are mosaic pieces made from an opaque vitreous glass or enamel in a multitude of colors called smalto. The smalto is pulled into rods or threads, called filati (spun enamel), and then left to cool. After cooling, it is cut into hundreds of minute cubes or tesserae and arranged on a copper or gold tray to create a scene, portrait, or landscape. During the mid-nineteenth century, black Belgian marble or “Noir Belge” was carved out and used as the background or base.

The metal or stone supports are then filled with mastic or cement upon which the tesserae are carefully placed and arranged into the desired image. Once the mastic has hardened, the gaps between the tesserae are filled with colored wax and the whole picture is polished to achieve a smooth and even surface.

It is an extremely laborious and painstaking art form. The mosaicist uses tweezers to apply hundreds, sometimes thousands, of tiny tesserae to create incredibly detailed and beautiful scenes. These mosaics could be fairly large panels or plaques inset on table tops or mounted on the wall, but more commonly they were made into much smaller oval or circular plaques that were worn as jewelry, incorporated into pendants, necklaces, earrings, brooches, and rings. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these plaques were often made in Rome, and exported to London or Paris where they were mounted in jewelry.

The term “micromosaic” was coined by the noted British collector of decorative arts, Sir Arthur Gilbert (1913-2001). Previously referred to as “Roman mosaics,” this term was thought to be historically misleading as, although these mosaics referenced ancient art, they did not exist until the late eighteenth century. Gilbert collected micromosaics throughout his life and amassed one of the largest collections in the world. His collection now resides in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and in The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in Los Angeles.

History

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

It is believed that mosaics originated in the Far East. Some of the earliest were found in Macedonia and were made out of pebbles and shells. These are dateable to the third century B.C. They became incredibly popular in Ancient Rome where they were constructed from small pieces of marble, terracotta, and glass and were often used to decorate the floors of villas.

The heyday of mosaics was during the Byzantine Empire (330-1453) when they were used to adorn the early Christian churches. They were popular because they were durable and could be incredibly sumptuous and grand, especially with the abundant use of gold leaf tesserae.

During the Renaissance (14th-17th century), the popularity of mosaics declined, surpassed by the grand-scale use of frescoes in churches. Although out of favor, mosaics were still produced during this period and into the Baroque (seventeenth-eighteenth century.)

There were some incredible pieces created during this time, most notably those designed by Michelangelo for the ceiling of the cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica. The interior of the dome is covered in some of the finest mosaics, using hundreds of thousands of tiny tesserae.

The Vatican Mosaic Studio, which still exists today, was initially part of a larger operation initiated by Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585) to work on the mosaics that were being installed in St. Peter’s and on the altarpiece in the Vatican Basilica. In 1727, the Vatican Mosaic Studio was officially opened. Its purpose was to convert some of the deteriorating oil paintings in the basilica to sturdier mosaics. Over 35 paintings were remade into mosaics.1With the opening of the Vatican Mosaic Studio and the increase in the number of papal commissions, there was naturally a rise in the number of artisans employed in this field. During downtime in papal work, many of these craftsmen began to experiment with the use of minute tesserae to make portable and much smaller works of art that could be sold to the private market for a profit.2

The demand for these new micromosaic plaques and pictures grew steadily, reaching its zenith circa 1840-70s. Their popularity was based on the stimulation of travel in Europe during the late eighteenth to nineteenth centuries. With the end of events such as the French Revolution and the following Terror, it was finally safe to travel again to the Continent. Coupled with the improvement of the political situation in Europe was the steady growth of the middle and merchant classes. Travel to Europe was no longer a privilege of the upper classes and nobility. British and American tourists flocked to the cultural capitals of Europe like Rome and Florence on what was called the Grand Tour.3The Grand Tour was seen as a rite of passage in the education of those from the upper class and nobility. The trip could last anywhere from a few months to several years. As transportation between Britain, the United States and the Continent became easier and cheaper, members of the middle and merchant classes undertook similar trips to Europe.

Photo Courtesy of Wikipedia.

The goal of each traveler on the Grand Tour was to soak in the culture of these cities and expose oneself to as much art and music as possible. It became incredibly fashionable to pick up mementos or souvenirs from these lengthy trips. One type, in particular, was micromosaic jewelry. These early pieces featured subject matter such as ancient Roman ruins, flowers, birds, animals, and images of bucolic Italian peasant life. Many of them were inspired by renowned Old Master paintings or contemporary landscapes.

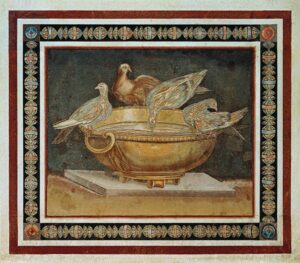

Later pieces featured subject matter inspired by the explosion of archaeological discoveries throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East during this period. In particular, ancient Pompeiian mosaics, motifs from Etruscan tombs, early Christian symbols, and hieroglyphs and emblems inspired by Ancient Egyptian artifacts. These trinkets were wonderful reminders of the amazing art that was being seen on these trips. A visit to the micromosaic shop became as important as visiting the famous ruins and museums when in Rome.4 An important early inspiration for micromosaics, both in subject matter and technique, was a wall panel measuring 3 x 2 ½ feet that was discovered at Hadrian’s villa outside of Rome in 1737. It was referred to as the “Doves of Pliny” and was one of the finest examples of ancient mosaics to be discovered. It was actually a Roman copy of a work by Sosos, a Greek artist from the Hellenistic Period (second century A.D.) and was constructed out of marble tesserae.

Mosaicists

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum.

Photo Courtesy of The Capitoline Museum.

Mosaicists were considered to be artisans and craftsmen, not artists in their own right. As a result, many of the pieces are unsigned. The life of a mosaicist during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was not an easy one. Most worked for studios or workshops, overseen by a head maestro. They worked long hours doing arduous and incredibly painstaking work. They were paid according to their skill. At the Vatican Mosaic Studio, many were only paid a scudo a day (less than a dollar) whereas they could be paid up to 4 scudi a day, if they proved their skill and talent, at one of the private workshops.5

Due to the high demand for micromosaics during the 19th century, there was an influx of non-skilled workers in Rome who made cheap, poor-quality pieces. These, unfortunately, flooded the market, hurting the reputation of the industry as a whole.6Although many mosaicists were never recorded, there was a group of exceptional artists that became famous during this period. The first of note was Giacomo Raffaelli (1753-1836). He executed an extremely fine version of the “Doves of Pliny” in 1779 that now resides in the British Museum.

Photo -Wikipedia.

Raffaelli was a founding father in the area of micromosaics, one of the first to incorporate micromosaics in jewelry, and he started the School of Mosaics in Milan. While there, he was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1809 to create a copy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s famed Last Supper in mosaic. It was finished after Napoleon’s abdication in 1814 when Milan was under Austrian rule. When it was completed, Francis II of Austria acquired it and wanted to place it in Belvedere Palace, but it was too large. Instead, it was installed on the north wall of the Minoritenkirche (Minorities Church, formerly the Italian National Church of Mary of the Snows) in Vienna where it resides today.

It is an incredible piece of work, showcasing Giacomo Raffaelli’s mastery of the art of mosaic. It measures approximately 30 x 14 feet and weighs 20 tons. It shows that he was adept at both large-scale mosaics as well as the much smaller micromosaics, so popular in jewelry during this period.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Another mosaicist of note is Clemente Ciuli, a contemporary of Raffaelli, who was active during the first half of the 19th century. Before Pope Pius VII (1742-1823) attended the coronation of Napoleon I in Paris in 1804, he asked the famed and noted sculptor, Antonio Canova, to draw up a list of diplomatic gifts that the Pope could present to the emperor. Among them was a grouping of micromosaics, with several by Ciuli. Two of these pieces are reputed to be in the Gilbert Collection at the LACMA in Los Angeles.

It is essential to record in these memoirs the name of another skillful practitioner of miniature mosaics, Signor Clemente Ciuli, residing at no. 71, Piazza di Spagna. We have seen a work of his that may be described as the ‘non plus ultra’ of monochrome work, or mosaics of one colour. On commission he has made the head of the celebrated colossal Jupiter formerly in the Salone Rotondo of the Museo Pio-Clementino, now in Paris. The minute scale, the uniformity and the invisible joining of pieces, suggests a drawing in chiaroscuro rather than a mosaic: and it should be noted that there could be no more difficult subject for a mosaic than such a Jupiter, in view of the difficulty of rendering that thick head of hair, and majestic beard, so well arranged, modelled and amassed by the ancient sculptor, that in this divine head is a masterpiece of human skill. Notwithstanding, the imitation made by Ciuili appears to be also of marble; nor can one understand how these marvellous tiny tesserae create the impression of the finest lines of the brush of a miniaturist.7

The noted Italian writer and archaeologist, Giuseppe Antonio Guattani, wrote in his Memorie Enciclopediche Romane Sulle Antichità e Bello Arti (1806-1819) about one of these pieces selected by Canova:

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Other mosaicists of note were Domenico Moglia (around 1780-1862); Antonio Aguatti (active during the first half of the nineteenth century); Liborio Salandri (active during the first half of the nineteenth century); Luigi Cavaliere Moglia (fl.1823-1878); Filippo Puglieschi (active during the first half of the nineteenth century) and Luigi Podio (d.1888).

Lastly, it is important to mention the work of Michelangelo Barberi (1787-1867) who was asked by Czar Nicholas I to come to Russia and start the Imperial Mosaic Studio of St. Petersburg. He is one of the most famous and financially successful mosaicists and was patronized by European nobility. He is noted for creating some of the most beautiful micromosaic table tops.

With patronage from such powerful figures such as Napoleon I and the Czar of Russia, the demand for micromosaics flourished during the late 18th-19th centuries. Both of Napoleon’s empresses are said to have owned parures with micromosaics.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861), the famous British poet, who spent the latter part of her life in Italy, was enamored with this type of jewelry. It is purported that her favorite treasure was a micromosaic brooch that is featured prominently in her portrait, painted in Italy in 1858.8

Hiram Powers (1805-1873), the celebrated American neoclassical sculptor, who also lived in Italy, is quoted as saying to his wife on her trip to Rome in 1847:

I give you liberty to buy a few cameos to send home to your sisters, or perhaps it would be better to get mosaics.9

Subject Matter

Attributed to Antonio Aguatti ( ?- c.1846) in a Private Collection.

Photo Courtesy of Micro-Mosaic.com.

In terms of subject matter, the early examples from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth centuries focused on themes such as pastoral landscapes, ancient Roman ruins, bucolic scenes of peasant life in Italy, floral images and animals, particularly portraits of recumbent dogs.

The most popular was the image of a seated spaniel. A perfect example of this popular motif is by Antonio Aguatti (active during the first half of the nineteenth century.) The attention to detail to the dog, particularly its fur is incredible. He was one of the first, along with Luigi Cavaliere Moglia (fl.1823-1878) to work with curved tesserae in order to suggest individual hairs.

These scenes and portraits were commonly set in plain gold rings joined by tiers of fine gold chains as necklaces and pairs of bracelets. By the late 1820-40s, the plaques were set in more elaborate cannetille frames, to create more opulent and striking pieces like the demi-parure illustrated below.

The pastoral landscapes of Rome and its surroundings depicted in these early micromosaics are particularly interesting as they reflect the relative provincial quality of the city before the increased urban growth of the 1870s.10

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

By the 1830-40s, there was a movement away from neoclassical themes toward scenes and subject matter inspired by the new archaeological discoveries of the eighteenth/nineteenth centuries. One of the most popular for micromosaics was the use of Egyptian motifs. The use of Egyptian designs and subject matter continued until the early part of the 20th century.

Interest in Egypt began in the late 18th century with Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign in 1798. By the early 19th century, artifacts brought back from these campaigns were appearing throughout Europe’s major cities. The use of Egyptian subject matter did not, however, appear in jewelry until the late 1820s. It is thought to have been prompted by the well-publicized deciphering of the hieroglyphic text on the famed Rosetta Stone by Jean-François Champollion in 1822.11

Castellani

Photo Courtesy of Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

An account of micromosaics would be remiss without a discussion of the enormous influence that Castellani had on this form of jewelry. Castellani was the most famous “archeological” jewelry firm of the nineteenth century. The company was founded in 1814 in Rome by Fortunato Pio Castellani (1794-1865). In the 1850s, Fortunato passed the running of the firm to his two sons, Alessandro (1824-1883) and Augusto (1829-1914).

The firm specialized in jewelry that was inspired by the archaeological discoveries of the time, particularly those from Italy. They did not focus on one period but instead produced pieces that were influenced or copied from all periods of Italian history. They worked primarily in gold. Augusto listed and described these periods in 1875-81 as a “chronological collection of goldsmith’s work executed in Italy during the various periods of its history, reproduced and displayed in eight cases.”12

Their studio, located in the fashionable Piazza di Trevi, consisted of a series of rooms filled to the brim with the company’s exhaustive collection of Italian artifacts, not only of goldwork but also of ceramics, bronzes, and terracottas. Visitors would pass from one room to next admiring the extensive collection, culminating in the last room that was filled with the firm’s work.

The fascination with all things Italian for the Castellani had deep roots in the Risorgimento, a popular movement in Italy during the 19th century. Since the 16th century, Italy had been torn up and occupied by various European countries, including, France, Spain, and Austria, to name a few. By the 19th century, there was a general feeling of dissatisfaction throughout the country with a growing movement among Italians to reunite the country. This culminated in the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861. It was not only a political movement, but also a literary, artistic and ideological one that sought to emphasize the greatness of Italian culture and history. Risorgimento literally means “Rising Again” in Italian.

According to Rudoe and Gere in their chapter on Archaeological Discoveries and National Identity in Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria:

The Castellanis’ scheme was an ingenious way to demonstrate within accepted boundaries their enthusiasm for the concept of a unified Italy. No other jeweller has ever centered its entire artistic creation so resolutely on a single political idea.13

The Castellani sought to use the past as inspiration in their jewelry in order to “produce a visual representation of the progress of civilization in Italy, ending in modern times.”14 Fortunato was joined in this belief of using jewelry as a means to promote Italian pride and craftsmanship with his good friend Michelangelo Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta (1804-1882). Caetani was a member of the Italian nobility who felt strongly, as Fortunato did, in creating a new type of jewelry that was inspired by the distinct periods of Italian art. They both felt that micromosaics were the perfect medium to explore art from the Medieval Period (periodo medioevale). Fortunato’s son, Augusto, writing in his 1878 survey of Italian industrial arts in 1840 stated:

…in 1852 Caetani, Duke of Sermoneta, and the Castellani family had the idea of combining mosaic with goldsmith’s work. Directing the mosaicist’s work according to the taste of the antique, they raised it to a finesse and perfection that harmonized superbly with their jewels and that mosaic had never reached. This example was most effective: large numbers of mosaicists abandoned the old style and imitated this new one, which had great success.”10

Michelangelo Caetani was responsible for many of the designs of these new micromosaics.

Another important source of influence for the Castellani was their friendship with the Russian count, Vassili Dimitrievitch Olsoufieff (1796-1858), a scholar and expert on early Christian art. Alessandro wrote in a paper in 1861:

We therefore made it our aim to reproduce in miniature some of the best ancient works in mosaic to be found in the old Basilicas of Rome, and in this endeavor we were greatly assisted by the learned Count Oulsoufieff, so celebrated for his knowledge of Graeco-Oriental art.15

Subject Matter

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Castellani, Private Collection.

Photo Courtesy of The Victorian Web.

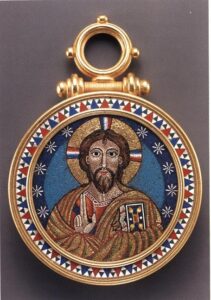

The micromosaics produced in the Castellani workshop were quite distinct in subject matter and technique from others being created at the time. Their inspiration came primarily from the mosaics found in early Christian and Byzantine churches. Many of their pieces incorporated Greek or Latin inscriptions.

The interest in early church art was influenced by the expansive series of restoration projects that were being carried out by Pope Pius IX (1792-1878) in Rome and the Papal States at this time.

Another source of inspiration, although not Italian, was the recent publication of mosaics at the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. From 1847-49, a pair of Swiss Italian architects, Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati, who were also brothers, were commissioned by Sultan Abdülmecid to restore the mosque. They brought to light the unbelievable mosaics that had previously been covered up. For the first time, color lithographs were available to study of this incredible Byzantine church that had been converted into a mosque in the mid-15th century. The influence on Castellani jewelry can be seen in the numerous micromosaics inspired or copied from these lithographic plates.

Typical subject matter for Castellani pieces were depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the lamb of God, symbols of the four Evangelists, Christian emblems, Latin and Greek inscriptions, as well as various cruciform designs.

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum.

Not only was the subject matter distinct, the technique was also different from previous micromosaics. Instead of polishing the entire piece to achieve a flat and smooth surface, the Castellani preferred to deliberately leave the surfaces uneven. The workshops left the tesserae at different heights. The purpose was to catch the light and make the piece sparkle. This glittering and shimmering effect was enhanced by the use of more gold tesserae to highlight and often act as the background to many of these plaques. The increased use of gold and the uneven surfaces was directly taken from early Christian and Byzantine mosaics that utilized the same techniques.

It should be noted however that the firm did not completely abandon the use of smooth surfaces, their modern interpretations of the “periodo medioevale” still utilized polished flat surfaces which were commonly seen in their plaques with Latin and Greek inscriptions.

Another innovation used in Castellani pieces was the use of gold or silver cloisons to highlight or delineate subject matter. These cloisins are referred to as fettucine (ribbons) in company ledgers.14 A technique commonly seen in enamel work, the Castellani’s incorporated it into their micromosaics as a means of highlighting an image or inscription. In the inscription plaques, they would create a word out of a contrasting color and then outline it with silver or gold cloisons on a single-color mosaic background. The overall effect was much more powerful and noticeable with the use of the silver or gold cloisins.

Photo Courtesy of Wartski.com.

The Castellani micromosaic plaques were usually set in lavish and extremely ornate goldwork frames often embellished with enamel. The frames were composed of beaded wire or ropework and flanked by pinecones, palmettes or other motifs inspired from the Classical or Medieval periods.

Photo © Trustees of the British Museum.

They also did away with the curved tesserae made popular by artists like Luigi Cavaliere Moglia and Antonio Aguatti. It had been popular because it added a sense of realism to the earlier nineteenth-century pieces. The Castellani firm advocated using the same geometric-shaped tesserae used in early church mosaics. The object of the earlier mosaics had been to create divine compositions that took the viewer outside of reality. The overabundant use of gold in these early mosaics was conscientiously employed to invoke awe in the person seated or standing below. The wealth and sparkle of these images were meant to dazzle the viewer and Castellani presumably sought to evoke similar feelings in these miniature masterpieces.

The firm was successful in its choice to depart from the old subject matter and techniques. These early Christian-inspired pieces were extremely popular. Castellani micromosaics were “highly prized at the time and contributed greatly to the fame and prestige of the firm.” 16

Castellani did not only produce micromosaics with Christian subject matter, they also created pieces inspired by other popular archaeological influences of the time such as motifs from Assyria and Egypt as these were also extremely fashionable and very saleable.

The quality and supreme craftsmanship that was typical of Castellani micromosaics can be attributed to Luigi Podio, the master mosaicist at the firm from 1851-1888. Augusto noted in his diary on March 2nd, 1888:

…after a short illness, the head of my studio specializing in mosaics has breathed his last. For my creation it is a loss; since 1851 he has worked exclusively for us. An ingenious artist and willing executor of our wishes he solved practical issues of mosaic in my jewelry. He was a man of absolute integrity.17

It is interesting to note that he was not mentioned in the firm’s ledgers and only referred to as the musaicista. The Castellani paid their mosaic workshop a flat rate which Podio then presumably split among his workers.

In 1927, the famous Castellani shop in the Piazza di Trevi closed its doors forever. Augusto was the last of the two brothers to pass away in early 1914. His son and heir, Alfredo, took over the firm and started the long process of donating the Castellani collection to the government. It had been Pio and Augusto’s wish to make the collection available to the public to the view. In 1929, the collection was moved to the Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia in Rome where it resides today. It contains both their extensive collection of antiquities as well as their modern creations.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, by the beginning of the twentieth century, the demand for micromosaics began to dwindle. New fashions and influences in jewelry overtook the need and desire for these miniature plaques. The Art Deco movement was now fashionable in all areas of the arts, including jewelry. It celebrated the modern world and derived its decorative vocabulary from geometry and advancements in technology, especially in the area of transportation. It did not look to the past and antiquity as micromosaics had but instead looked to the future for inspiration.

Sadly the demand for these exquisite works of art never came back in fashion and the production of newer pieces was relegated to poor quality, cheap souvenir trinkets. There are still a handful of master mosaicists working today in Rome with great skill and technique, but it is, unfortunately, a dying art form.

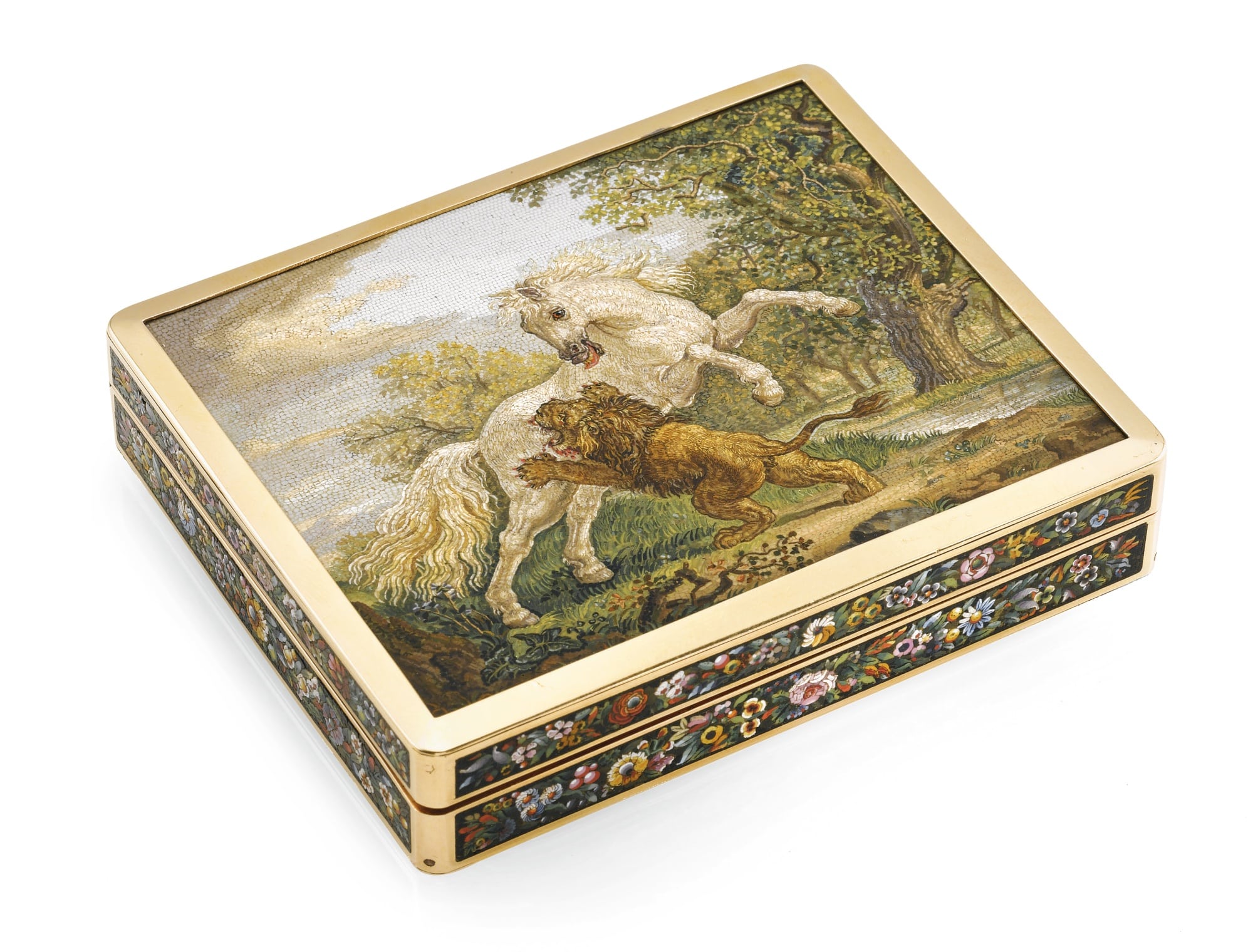

In the last few years, there has been a resurgence of interest in jewelry and decorative arts from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A recent auction at Sotheby’s offered an exceptionally fine early nineteenth-century micromosaic snuff box which realized $170,000. The level of expertise and artistry in this box showcases the best of nineteenth-century micromosaics. Hopefully, with the publicity of more of these miniature masterpieces, the micromosaic will find favor again.

Sources

- Benjamin, John, Starting to Collect Antique Jewellery, Suffolk: The Antique Collector’s Club, 2003.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela, Understanding Jewellery, Suffolk: The Antique Collector’s Club, 2011.

- Bury, Shirley, Jewellery: The International Era 1789-1910, Volume II 1862-1910, Suffolk: The Antique Collector’s Club, 1997.

- Gere, Charlotte & Rudoe, Judy, Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria, London: The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Grieco, Roberto, Micromosaici Romani, Rome: Gangemi Editore, 2001.

- Mack, John, The Art of Small Things, Boston: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Soros, Susan Weber & Walker, Stefanie, Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Notes

- Grieco, 17.↵

- Grieco, 20.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 489.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 154.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 168.↵

- Greico, 32.↵

- Mack, 34.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 494.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 500.↵

- Soros & Walker, 154.↵↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 379.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 401.↵

- Gere & Rudoe, 400.↵

- Soros & Walker, 155.↵↵

- Soros & Walker, 157.↵

- Soros & Walker, 153.↵

- Soros & Walker, 170.↵