Introduction

A necklace can be defined simply as an adornment designed to encircle the neck. Upon closer examination, they are actually so much more. Having existed ever since our ancestors began to walk upright, early necklaces were crafted from objets trouvés – shells, bones, teeth, and claws. We know this through discoveries made during archaeological explorations.

As our sophistication and knowledge grew so did the variety of materials and the level of detail and design used in jewelry. Some necklaces took on a specific purpose and symbolism, while others remained simply adornment. As we enter the era of mechanization, diamond and gem cutting become more varied and sophisticated and these advances in metallurgy and gem-setting techniques influenced the possibilities for necklace design. An increasingly diverse selection of gem materials from newly discovered deposits worldwide contributed to the mix. Meanwhile, improvements in lighting for evening venues became a factor in fashion, especially jewelry.

18th Century

Diamonds were the premier gem of the first half of the eighteenth century. This fascination with diamonds arose from the newly developed ability to facet them thereby more efficiently reflecting and refracting light. Diamonds were more brilliant than ever before. Daytime diamond wear was now permissible, but the more extravagant jewels were still reserved for evening and candlelight. Diamonds were set in silver with closed-backs until mid-century when open-back settings came on the scene. Flowers and bows were the prevalent theme and parures were all the rage with a magnificent necklace as the centerpiece. Cameos were employed in jewelry making at unprecedented levels. They could be found in tiaras, necklaces, brooches, bracelets, rings, virtually every type of jewelry and accessoire imaginable.

During the latter half of the eighteenth century, colored stones came back into style. Rivières linked together long lines of individually set stones, sometimes diamonds, but often colored stones. The popularity of the rivière has never been seriously challenged; a classic on into the twenty-first century.

Guilloché is a decoration of concentric design engraved on metal, through the use of a lathe, resulting in an elaborate pattern. These elegant and usually quite intricate designs are often covered by translucent enamels which serve to highlight the pattern. This technique was especially popular around the fin-de-siecle. Carl Fabergé

was a master at using guilloché and employed the technique extensively in creating his jewelry, clocks and other objects de virtu.

Also referred to as engine-turned.

18th Century, Europe

- Deep décolleté, short necklaces worn tightly around the neck.

- Wide gem-set bands, sometimes with a bow or cross pendant.

- En Esclavage – openwork band suspending festoons and pendants.

- Pendants were detachable for versatility.

- Necklaces were tied in elaborate bows at the back by ribbons run through looped terminals. The use of ribbons made necklace lengths variable/adjustable.

- Rivière – line of gemstones (usually graduated) in plain collets. Sometimes suspending a large diamond pendant.

- Daytime necklaces were less precious, nighttime was reserved for diamonds.

- Silver mounts with closed backs for diamonds and gold mounts for colored gems.

- Foil lining provided uniform coloring for gemstones.

Late 18th Century, Europe

- Gold backings for silver necklaces to prevent tarnish on skin.

- Open-backed collets.

- Metal spring ring clasps began to replace ribbons for closures.

19th Century

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

An interesting development c.1804 was the manufacture of Berlin ironwork jewelry. First produced at the Royal Prussian Foundry, black enameled pieces with geometric wire patterns were created. These works quickly morphed into the neo-classical style that was so popular throughout Europe. Necklaces featuring repoussé medallions depicting classical scenes were suspended or interspaced by fine chainwork. Napoleon captured Berlin and confiscated the molds making it extremely difficult to determine the origin of ironwork – French or German? The Germans used the iron jewelry to turn the tables on Napoleon by donating their jewels in exchange for iron jewelry to fund their fight for independence. The public had a love affair with the delicate iron tracery and the material remained in use throughout a switch to realistic design and a revival of Gothic themes.

The fall of Napoleon led to relative poverty in France resulting in a brief period were the style was no jewelry at all. When French jewelers finally went back to work diamonds were out of favor as modestly priced colored stones were preferred. Cannetille parures set with colored stones in realistic floral motifs were all the rage. The archaeological discoveries throughout the world would fuel a European-wide style that referenced ancient civilizations alongside the fashion for more romantic jewels in the Renaissance and Gothic styles. Necklaces featured micromosaic and pietra dura plaques connected by chainwork, whole suites of cameos, beautiful bead and wirework designs and fabulous enameled pendants in the Renaissance style.

Mourning jewelry items included pendants and neckchains carved from Whitby jet, and woven from human hair. Sentimental lockets and medallions proclaiming “Forget Me Not” were suspended from chains. New methods for mass-producing fashion jewelry were being developed in England. Electro-plating, faux gemstones, stamping, and other techniques created jewelry at a faster pace and for more consumers than at any time in history. Silver discoveries made this metal more available and affordable and millions of silver jewelry items were produced quickly as a result of the mass production capabilities in England.

A backlash to the overproduced poorly stamped jewelry in the latter half of the nineteenth century resulted in a new aesthetic and philosophy seeking to revive the crafts, Art Nouveau. The free-flowing “whiplash” designs of Art Nouveau were employed in making incredible pendants and necklaces decorated by a veritable rainbow of colorful enamels, employing various enamel techniques including plique-à-jour and all manner of interesting if not valuable gems. Themes from nature especially flowers, insects, and birds as well as fantastic mythological creatures and female figures combined with a multitude of creatures are the signature designs of the period.

19th Century, Europe

- Décolleté still the fashion.

- Lighter, flatter more linear necklaces.

- Broad use of cameos and intaglios.

- Rivières were still popular now connected by links instead of ribbon.

- Clusters of stones with a central motif linked by fine gold chains to matching graduating smaller motifs.

- Long necklaces draped sash-like over one shoulder diagonally across the body.

- Semi-precious daywear gems, precious in the evening.

c.1815-1837, Europe

- Décolleté became a straight across and off the shoulder. For day wear a ruff or collar was added for modesty.

- Necklaces were shorter with large girandole, pendeloque and cross motif detachable pendants.

- Colorful foiled gems mounted in cannetille.

- Repoussé decorative elements with colored gemstones.

- Polychrome enamel designs often used instead of gemstones.

- Parures were a fashion necessity.

1837-1859, Europe - Romantic Period

- Daywear concealed nearly all of a woman’s body.

- Nighttime straight across décolleté was still in vogue.

- Large bodice ornaments nearly replaced necklaces altogether.

- Short necklaces were worn at the base of the neck with naturalistic designs: fruit, flowers and serpents.

Ac.1860-1885, Europe - Grand Period

- Necklaces were popular again and for evening wear the décolleté was very deep.

- Souvenier jewelry included mounted hummingbird heads, teeth, animal claws, shells, tortoise shell pique, micromosaics, carved cameos and lava jewelry.

- Archeological styles, with ancient techniques, were used to design short necklaces, with a chain or a band foundation, suspended numerous pendants all around, usually in a fringe.

- Renaissance and Gothic revival styles with elements from architecture and sculpture were combined with symbolism and heraldry and decorated with polychrome enamels.

c.1885-1901, Europe - Fin de Siécle

- Diamonds discovered in South Africa provided ample stones to make magnificent creations with emphasis on intrinsic value over design.

- Rivières were extremely popular and were made of large fine quality diamonds, mounted in open collets with a gallery. Often convertible to bracelets and other items.

- The bust, underscored by an uplifting corset, became the focal point of feminine fashion.

- Covered to the neck in the daytime and displaying a deep décolleté in the evening.

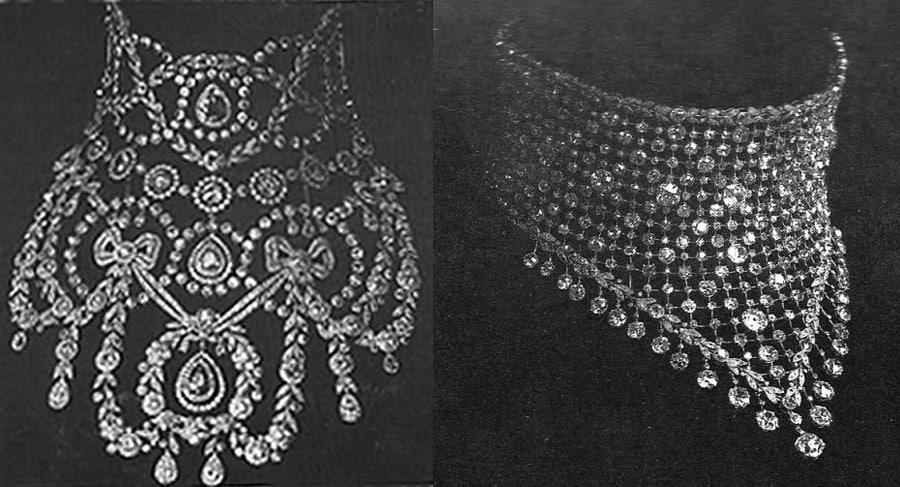

- Choker: Very wide and snuggly fitted to the individual neck.

- Résille: necklaces of finely netted meshwork set with diamonds.

- Collier de Chien: Wide with a plaque on a ribbon or multiple rows of pearls.

- Continuous lines of articulate plaques.

- Fringe necklace: At the base of the neck (below the choker) designed as a series of pendants suspended like fringe and usually could double as a tiara with the addition of a framework.

20th Century

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

At the turn of the twentieth century, newly delicate styling was made possible by the use of platinum in combination with diamonds. Evolving alongside Art Nouveau this new aesthetic became known as Edwardian (or Belle Époque in France). Pendants of incredible detail and airiness suspended from equally fine chains were in vogue. Chokers and colliers de chien were often combined with sautoirs and longchains. Incredible, intricate, garland design necklaces completely encrusted with diamonds glimmered under the electric lights of evening.

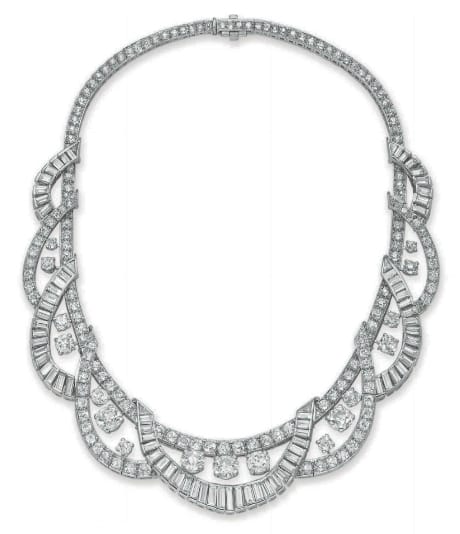

As World War I ramped up, Art Nouveau fell out of favor and, at the conclusion of the war, Edwardian was gone as well. Once the dust cleared, a demand for a more ostentatious style of jewelry arose. Combining this new demand with the popular Cubist movement in the arts resulted in the distinctive geometric jewelry we call Art Deco. Necklaces were made of platinum and decorated by round brilliant and emerald-cut diamonds with colored stones providing contrast, often calibré-cut to create delicate outlines. Long sautoirs, infinite strands of pearls and négligées adorned the neck and provided elongated decoration on the new dropped waist straight silhouette.

The retro period saw the return to the use of gold in jewelry. Bold highly polished mechanical links in rose, yellow and green gold made distinctive collars encircling the neck. Post-World War II once again saw platinum come into vogue. The rivière was restyled to include new diamond shapes such as the pear and marquise. These chokers were often set all around with diamonds and suspended diamond or pearl pendants. Pearl necklaces were another favorite during this period and they were most often composed of double strands of graduated pearls. Bead necklaces in all types of gem material were considered appropriate for day wear. Gone was the parure but matching necklace and earring suites had stepped in to take their place.

Belle Epoque:

- “S” curve silhouette with prominent bustline and deep décolleté.

- Diamonds & platinum – Lacy and delicate scalloped necklaces featured:

- Swags.

- Garlands.

- Flowers.

- Bows & Ribbons.

- Résille or Draperie de décolleté(Collar that flowed downward from the neck)

- Often more than one necklace at a time was worn: Collier de chien, Lavallière, Négligée, Scalloped/swag necklaces, and Rivières.

Edwardian:

- Sautoirs complimented the new straight shift dress designs c.1910.

- Ropes or bands of seed pearls with tassels or pendants.

- Geometric styling.

- Often with detachable pendants and could be worn short or long or converted to bracelets.

- Collier de chien:

- Plaque with pearls or ribbon.

- Black velvet ribbon with lacy diamond applique.

- Band of pearls or pale gemstones.

- Long strands of pearls worn in multiples.

Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts c.1900-1915, Europe

- Jewels inspired by nature.

- Birds, flowers, animals and the feminine form.

- Design more important than intrinsic value.

- Central enamel and gem-set plaque on multi-strand pearl choker.

- Lavallière and en esclavage designs dominated.

Materials selected to compliment the design.

- Horn.

- Agate.

- Enamel.

- Opals, moonstones, pearls and other pale gems preferred.

Art Deco c.1920-1940

1920s

- Strait shifts, short skirts, and masculine hairstyles all remained in vogue after the war.

- Sautoirs with long lines swinging freely – very geometric, and convertible.

- Egyptian, Oriental and Indian motifs.

- Bold gemstone combinations, vivid colors with extreme contrasts.

- Rock Crystal and Black Onyx.

- Emeralds, Rubies and Sapphires together.

- New diamond cuts/shapes and calibré-cut gemstone combinations.

1930s

- Shapelier fashions required shorter necklaces.

- Low-backed evening gowns required pendants suspended from the clasp.

- Graduated “festoon” collars.

- Monochromatic /diamond-2/ only necklaces.

- c.1935 colored gem cabochons became the focus.

- Burmese rubies were especially popular due to the fact that they dazzled under electric light

Retro c.1940s

- Fashion: tailored severe suits and practical dresses.

- Wartime ban on platinum.

- Gold use was restricted.

Thin, low carat gold jewelry:

- Gold often supplied by customer.

- Flexible/convertible snake chain, gas-pipe and hollow designs with applied/removable motifs were very popular.

- Scarcity of fine gems resulted in the use of:

- Recycled gems from older jewelry.

- Synthetic rubies.

- Large gemstones such as aquamarine, amethyst, and topaz.

1950s

- Prosperous post-war period, luxury in vogue again.

- Feminine “puffed” skirts with narrow waistlines with emphasis on the bust-line.

- Shorter Necklaces with curving flowing lines often asymmetrical.

- Platinum, palladium and white gold.

- Diamonds as the primary gem were sometimes punctuated by rubies, emeralds, and sapphires.

- Lavish diamond rivieres supported fringes, festoons, and drops.

- Channel-setting popular with baguettes forming lines and outlines.

- Gold was woven into textile-like patterns and designs with small diamond accents.

- Pearl necklaces were back, singly, in pairs and festooned with diamond accents.

Related Reading

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Black, J. Anderson. A History of Jewelry: Five Thousand Years. New York: Park Lane, 1975.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington Dawes with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714-1830: Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Mascetti, Daniela and Triossi, Amanda. The Necklace: From Antiquity to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Jewellery in Britain: 1066-1837, Wilby, Norwich: Michael Russell, 1994. Pp.168-169.