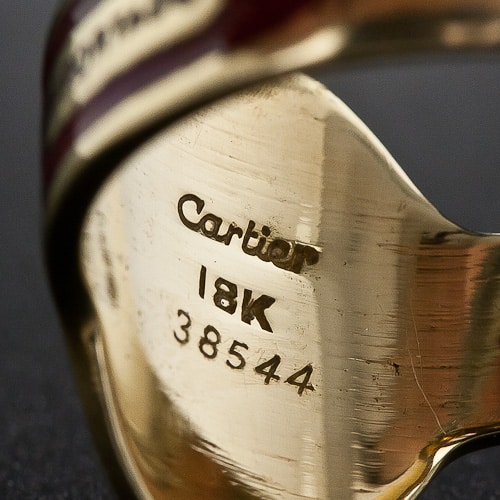

The illustrious firm of Cartier has been at the forefront of some of the most important jewelry design trends of the 20th century. Ranging from the opulence of La Belle Époque, the geometry, and exoticism of the Art Deco movement to the development of the classic wristwatch and ornate clocks, Cartier has created some of the most iconic pieces in the history of jewelry. They have exerted an enduring influence on design and craftsmanship and have become one of the most widely recognized symbols of luxury and elegance.

Origins

Founded in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier in Paris, during the period between the abdication of King Louis Philippe and the establishment of the second empire, the firm of Cartier initially had to overcome difficult financial times fraught with intense competition.

Surviving these early hurdles, Cartier began to thrive. By 1856 they had secured the patronage of Princess Mathilde, second cousin of Napoleon III and, shortly thereafter, the Empress Eugénie as well. The financial rewards and the prestige accrued as a result of becoming a purveyor to the imperial household allowed the young firm to move to a larger and more desirable site on the Boulevard des Italiens circa 1859. They continued to service a steadily increasing number of the well-to-do, including many members of French royalty, as well as aspirational bankers and industrialists.

During this period, Cartier stocked a wide assortment of luxury goods including porcelain, silverware, bronze busts, and medallions as well as jewelry and watches. Cartier, along with many other Parisian jewelers, were retailers rather than designers or manufacturers of jewelry, commissioning work from the various workshops and well-established firms in the vicinity of Paris such as Fossin, Delamarre, and Lalique. The jewelry historian Hans Nadelhoffer wrote of this arrangement:

The stock of a business like Cartier’s brought together the products of three different professional groups which, ever since the Middle Ages, had jointly formed one of the most distinguished of guilds: the goldsmith who made silver and gold vessels, the bijoutier-orfevre who manufactured gold and enamel jewelry and snuff boxes, and the joaillier who restricted himself to working with gemstones.1

While distinguishing themselves as a successful business, Cartier’s jewelry pieces became notable for the fineness of their execution rather than for any originality in design. They firmly reflected the prevailing tastes of the era by retailing mainly Gothic and Renaissance Revival style jewelry that comprised the current fashion. While Cartier would soon establish design and manufacturing workshops of their own, they would continue to rely on specialist workshops for creating certain pieces.

Rue de la Paix

The history of modern Cartier really begins with the move in 1899 to their current location, the epicenter of the French luxury trade, the rue de la Paix. Cartier had been under the leadership of Louis-François’s son, Alfred since 1874, and he was joined at the new location by his 21-year-old son, Louis. In addition to housing many of the most famous jewelry firms of the day such as Mellerio, Vever, and Aucoc, the famed street was also the address for the great fashion houses, most particularly the distinguished firm of Worth. Together, the houses of Worth and Cartier were instrumental in ensuring that the rue de la Paix became the preeminent shopping address in the world. Indeed, crowned with the smashing success of the Exposition Universelle in 1900, Paris was considered the reigning center of fashion and luxury, drawing an elite clientele from all parts of the globe.

Belle Époque

The move to the rue de la Paix coincided with a period of extraordinary economic growth and affluence in France and the world. Cartier was also growing and expanding and had started to shift their emphasis from retailing to design and manufacturing. Although they produced a small number of pieces in the Art Nouveau style, Cartier paid scant attention to the movement. They made their distinguishing mark in pioneering the use of platinum in creating the delicate and graceful Garland style that came to be associated with the Belle Époque. The discovery of the great diamond deposits in South Africa in the late 1860s engendered the popularity of extravagant diamond jewelry. The technical advances in the manufacturing of platinum enabled designs of great intricacy, strength and flexibility such as found in the spectacular résille designs of Cartier. (See Edwardian Jewelry: 1901-1915). As the art historian Martin Chapman noted:

Overcoming the inherent difficulties of the metal, such as its high melting point, Cartier exploited the means whereby platinum, which had been known but overlooked for well over a century, could be worked into the most delicate settings for jewelry. Apart from everything else, it meant that a plentiful supply of diamonds could be compressed into a setting without making the piece too heavy, as would have happened with silver or gold.2

The Garland style, taking its inspiration from the sumptuous setting and pomp of Louis XIV’s Court of Versailles, incorporated bows, flowers, laurel wreaths, vases and garland motifs. Eighteenth-century pattern books were used extensively as inspiration and Louis Cartier also encouraged his designers to keep note of the interesting and ornate architectural details that were to be found throughout the buildings of Paris. Cartier excelled in adorning both royalty and the very well-off in the ornate stomachers, epaulettes, corsage ornaments, dog collars, lavalieres and tiaras that the elegant and formidable fashions of the day demanded.

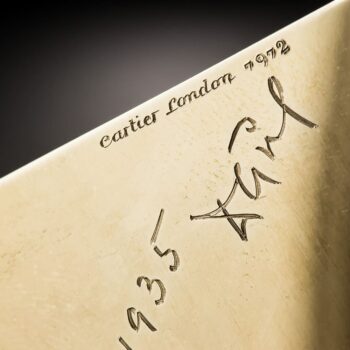

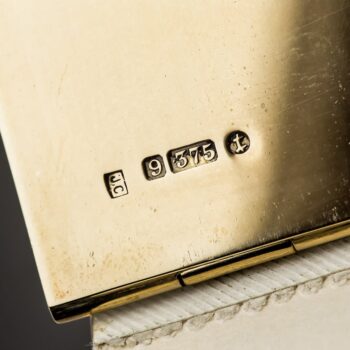

London, New York & St. Petersburg

Cartier marked the beginning of the twentieth century by opening branches in London and New York, where their wealthiest and most dedicated clientele resided. The 1902 coronation of Edward VII occasioned a large number of commissions from England’s leading families. Records indicate that Cartier produced twenty-seven tiaras alone for the coronation and the event was instrumental in convincing the firm to seek a permanent presence in London. Indeed, by 1904 they had achieved their first of fifteen royal warrants being appointed official purveyors to the court of King Edward VII. The London branch came to thrive under the tutelage of Alfred’s youngest son, Jacques Cartier, establishing London-based design and manufacturing workshops.

Opening a Cartier store in New York was a natural progression as many of America’s wealthiest families and business magnates had been traveling to Paris for some time to purchase their jewels from Cartier. By 1906 Alfred had largely retired and Louis and his brother Pierre operated the Cartier business jointly. One of their first major decisions was to establish a New York presence and workshop in 1909 under the skilled direction of Pierre. Indicative of his business skills, Pierre famously secured Cartier’s present location, an elegant Beaux-Arts mansion at 653 Fifth Avenue, from industrialist Morton F. Plant in 1917. The building changed hands in exchange for $100 and a double strand of natural pearls, admired by Plant’s wife and valued at one million dollars, the asking price for the mansion. While the Fifth Avenue location remains priceless to the firm, when the pearls came up for auction in 1957, they fetched a mere $170,000.

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

Louis Cartier also temporarily established a branch of the firm in St Petersburg in 1908. He ambitiously attempted to capture the Russian market by introducing the latest in Paris jewelry fashions and by directly taking on the famed firm of Fabergé by creating the beloved hard stone sculptures and enamel objects for which they were so renowned.

By all accounts, before the Bolshevik revolution necessitated its closing, Cartier had made significant inroads into the Russian market: creating two ornamental eggs (one a gift from the city of Paris to Tsar Nicholas securing the patronage of the Grand Duchess Vladimir) and creating an unusual rock crystal and diamond wedding tiara for the immeasurably wealthy Princess Irina Youssoupoff.

The extensive traveling that the brothers undertook furthered their international renown and enriched their design aesthetic. Their travels throughout India, Russia the Persian Gulf, Siam, and China brought them both exceptional gems and numerous clients in royal courts and high society throughout the world. It also brought inspiration to their jewelry designs, helping to establish the firm as one of the foremost exponents of Art Deco design.

Art Deco

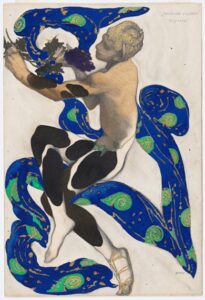

The year 1910 was a turning point in the design history and influence of Cartier. Inspiration was to be found everywhere: exotic lands, the new modernist movement of Cubist painters such as Picasso and Braque and the bold colors and techniques of artists such as Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Cezanne as well as the strong aesthetic impact of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Cartier’s art deco pieces are characterized by vivid colors such as coral, jade, and lapis and contrasting opaque and translucent materials such as onyx and diamonds. These unusual combinations created bold and surprising color combinations, imbuing the geometric lines of the Art Deco movement with a decidedly exotic influence from Egyptology, the Far East, India, and Persia.

While this pioneering style was being produced well before the outbreak of World War I, the movement was not formally recognized until the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes which spawned the term Art Deco. Cartier’s brilliant display at the exposition was notable not only for its sumptuous jewels but also for the fact that they were the only jewelers, of approximately 400, to exhibit with the fashion houses in the Pavillon de l’Elegance rather than with the jewelers in the Grand Palais. This choice further underscored Louis’ firm belief in the unity of the decorative arts. Hans Nadelhoffer sums up this synthesis:

At this period we should not forget that the contacts between the arts and crafts, theatre, literature, and soon film, were manifold, vigorous, and taken for granted and that they yielded undreamed-of possibilities of inspiration. Louis Cartier, for example, cultivated his connections with Diaghilev, Sert, Foujita and Christian Bérard; he knew the most talented innovators in fashion and décor-Jacques Doucet, Jeanne Lanvin, and Coco Chanel: he admired Paul Valéry and Jean Cocteau and had social contact with the brilliant Elsie de Wolfe, Misia Sert and Louis Vilmorin.3

Egyptian & Tutti Frutti

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

The influence of ancient Egypt had been a factor in the world of art and design since the eighteenth century. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 furthered this interest as did the 1911 Franco–Egyptian Exhibition at the Louvre. Cartier’s early Egyptian-inspired pieces used scarab motifs, lotus blooms and other recognizable symbols wrought in lapis, turquoise and garnet, highlighted by pearls and diamonds. Pieces in the early 1900s include stylized motifs worked in platinum with diamonds and onyx and punctuated with designs made of calibré-cut emeralds, rubies and sapphires. Following the exciting discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb by Howard Carter in 1922, the interest in the Egyptian style greatly intensified. Perhaps inspired by Louis Cartier’s long-standing personal interest and collection, Cartier began designing unique and imaginative pieces around ancient Egyptian faience beads and fragments.

Cartier’s combination of ancient components set in contemporary mountings was also found in the Indian style jewelry that used rare, carved Mughal stones, most memorably emeralds. These stones were Colombian emeralds that had been imported to India since the late seventeenth century and the carvings were based on the Islamic flower cult of the Moghul emperors. In addition to the rare ancient Moghul gems, Cartier also imported a large quantity of carved ruby, emerald and sapphire leaves from India that they used in their iconic multi-gem “tutti frutti” style of jewelry. From the first piece produced in 1923, tutti frutti has retained its popularity and is still highly sought after today. Indeed, a splendid Art Deco tutti frutti bracelet produced by Cartier circa 1928 was auctioned in June 2011 by Christie’s for an impressive record-setting price of $1,887,232.

Charles Jacqueau

Although none of Cartier’s designers were noted individually as the firm’s policy was to promote the Cartier name singularly, the history of the firm would not be complete without acknowledging the influence and brilliance of its chief designer Charles Jacqueau. While many of the Cartier design archives are unsigned and difficult to attribute, a number of Jacqueau’s designs have survived, descended from his personal collection. He joined the firm as a young artist in 1909 and is credited with creating some of the most innovative and artful pieces of the teens and twenties. Taking design inspiration from numerous decorative motifs originating in Egypt, Islam, India, China and Japan, Jacqueau’s interests and inspirations were eclectic and original. Nadelhoffer writes:

The greatest service he rendered Cartier’s and contemporary design in general was to abandon the garland style, espouse bold colors and design, and become the champion of a new aesthetic which, following the First World War, was given official but belated recognition at the 1925 Exposition Internationale Des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes and which later gave its name to an entire period of early twentieth-century art.4

found inspiration during his various travels to Italy, Russia, Morocco, and Spain as well as closer to home in the varied exhibits at the Louvre, and the striking costumes, colors and movement of the Ballets Russes, particularly their use of the vibrant combination of blue and green. Jacqueau was instrumental in setting up Department S (S for silver) with Louis. The department was established between the wars, expanding on their remarkable range of luxury objects, such as elaborate desk accessories, cigarette, and vanity cases, by creating still beautiful but relatively affordable functional objects. This echoed Jacqueau’s design ethos that less expensive materials such as coral and agate could be used in the same design with the most expensive gems such as diamonds and emeralds and that great design could be exemplified in setting off a priceless stone with a simple silken cord.

Jeanne Toussaint

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

In 1914, Cartier introduced a diamond and onyx watch with a design by Charles Jacqueau which was the first of their jewels to feature the peau de panthère style. The panther motif and imagery had long been popular in Europe and the black and white pattern was very much in vogue, particularly in interior décor. In 1917, Louis Cartier had the first fully representational panther piece created atop a black onyx vanity case for Jeanne Toussaint, whom he affectionately called “Panther”. Jeanne Toussaint, (1887-1978) initially the creative director of Department S was, by 1933, overseeing Cartier’s haute joaillerie department where she reigned for several decades as a highly influential creative force. While not a jewelry designer herself, Jeanne Toussaint had an unerring eye for fashion and design, known in her younger years for wearing dramatic turbans and long strands of pearls. She is widely credited with several key design motifs by Cartier including the development of the now-iconic range of panther jewels.

c.1914.

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

Judy Rudoe writes:

…she was almost certainly responsible, for example, for the fashion for wearing imported Indian jewellery. In the late 1930s, quantities of gold and gem-set jewellery were purchased in India by Cartier London agents at her request. After the Second World War, it was Toussaint who, in collaboration with the designer Peter Lemarchand (1906-70), developed the earlier panther motif into a three-dimensional representation of the animal studded with sapphires instead of onyx and seated on a huge sapphire for a brooch made for stock in 1949 and purchased by the Duke of Windsor as a present for the Duchess.5

Further exploration and development of the panther motif were facilitated by an affiliation between Jeanne Toussaint and Peter Lemarchand, a graduate of l’École Boulle, who joined Cartier in 1927. Perhaps the most well-known and important of the panther pieces ever produced is the fully articulated bracelet with diamonds and calibré-cut black onyx created for the Duchess of Windsor in 1952. The piece was auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2010 for a breathtaking seven million dollars making it the most expensive bracelet ever sold at auction.

Another noteworthy example of Toussaint’s collaborative efforts and felicitous relationship with the Windsors is the famous Flamingo clip brooch crafted with stones from the Windsor’s own collection and famously delivered to them just days before Germany’s 1940 invasion of Paris.

Clocks & Watches

c.1910.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Cartier originally met their client’s demands for timepieces by buying important pieces at auction and making selections from specialist dealers. In the 1890s they were chiefly supplied by the great watch-making firm of Vacheron & Constantin of Geneva. Following the move to the rue de la Paix, Louis Cartier had ambitious plans to expand Cartier’s offerings, focusing on table clocks, greater in-house production and promoting the further development of the wristwatch.6

The table clocks of the early 1900s were designed to reflect the same garland-style eighteenth-century décor aesthetic used to inspire their jewelry, incorporating wreath, vase and garland motifs. The materials used in their manufacture were marble, hardstone, and porcelain with enameled and jeweled cases. A number of different firms were involved in the production of Cartier table clocks including movements supplied by the firms of Bredillard and Prevost and enameled cases by workshops such as Dubret. Later models, inspired by the work of Fabergé, were enameled in pastel shades of violets, pinks, pale blues and spring greens over engine-turned designs. The most innovative and spectacular of the Cartier table clocks, however, are the ‘mystery clocks’, which made their debut in 1913.

Photo Courtesy of Cartier Collection.

The talent behind these iconic timepieces was a young watchmaker, Maurice Couet (1885-1963). He first learned the craft at his father’s workshop in Evreux and further honed his skills in the Paris studio of Prevost before eventually setting up his own workshop. By 1911 Couet was supplying table clocks exclusively to Cartier and eight years later, in 1919, he set up the Cartier clock workshop at the rue Lafayette employing a number of diverse and highly skilled specialists including lapidarists, watchmakers, enamellers and stone setters. Along with Couet, the workshop had its own team of clock designers but many of the more important pieces, including Mystery Clocks, were designed by the Cartier jewelers Charles Jacqueau and Georges Remy.

The hands of a mystery clock seem to operate by themselves, keeping time around a transparent face, typically made of rock crystal, with no visible connection to a movement. Each hand is in fact fixed onto a separate crystal disc set with a saw-toothed metal rim that is driven by gears disguised within the frame of the case. Each part of the clock is completely hand-made and production of a completed clock, even into the 1980s, was a painstaking and laborious process requiring three to twelve months to complete. The first mystery clock created, called the ’Model A’ with a vertical frame and heavy stone base, was sold to J.P. Morgan. Subsequent models incorporated many different shapes and motifs often with Oriental themes including the famous Portico models, which were designed as freestanding Oriental porticos featuring dragons or Buddhas.

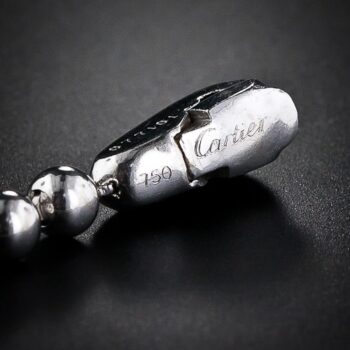

Cartier first started producing ladies’ wristwatches in the late 1880s. These small, jeweled creations typically featured rectangular, octagonal or round bezels, pavé-set with diamonds and fitted with black moiré silk straps, or bracelets of fine black cord or seed pearls. It was not until the early 1900s when fashion allowed for shorter sleeves and evening wear, without long gloves, that wristwatches became appreciated as a fashion jewelry item. Tonneaus and oval baignoires models gained quick popularity and cabochon ruby, sapphire, or pearl winding buttons became associated with the firm.

While women were wearing their jeweled wristwatches, the pocket watch was still favored by men up through the first decade of the 1900s. That was to change with the debut of two now-iconic wristwatches: the Santos and the Tank. The Santos wristwatch was created in 1904 for the famed Brazilian aviator, Alberto Santos Dumont. A friend of Louis Cartier, he had difficulty using a pocket watch to gauge his performance time while in flight. Strapping on a wristwatch proved eminently practical and the Santos Dumont wristwatch officially went on sale to the public in 1911. The Cartier tank watch, whose clean lines are reputed to have been inspired by the silhouettes of American tanks in Europe during WWI, was designed by Louis Cartier in 1917 and went on sale two years later.

Just as Cartier’s clock department was able to employ the extraordinary talents of Maurice Couet, their small watches came under the purview of another great talent, Edmond Jaeger (1850-1922). Jaeger learned his trade working for several well-respected companies, the most formative of these was the Breguet workshops in Paris. By 1905 he had his own company and in 1907 signed a fifteen-year contract with Cartier giving them exclusive rights to his products. The European Watch and Clock Company was founded in 1919 as a joint venture between Cartier and Edward Jaeger and supplied nearly all of the watch movements for Cartier Paris. Cartier also worked with such well-known watch and clock firms as Vacheron Constantin, Patek Phillipe and Audemars Piguet.

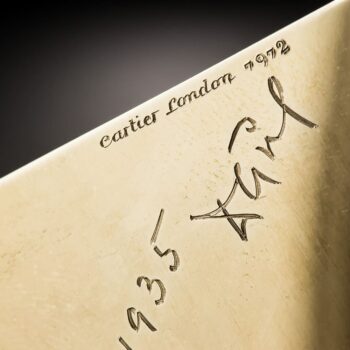

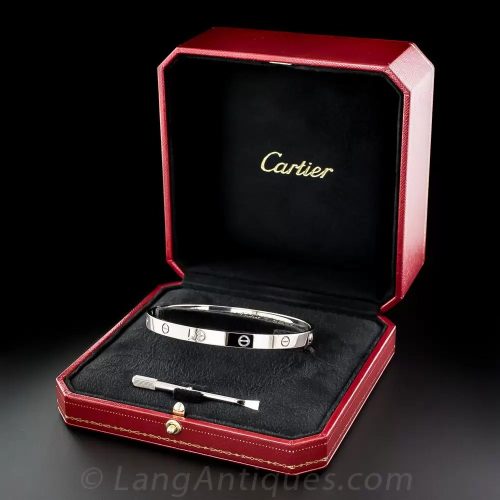

Modern

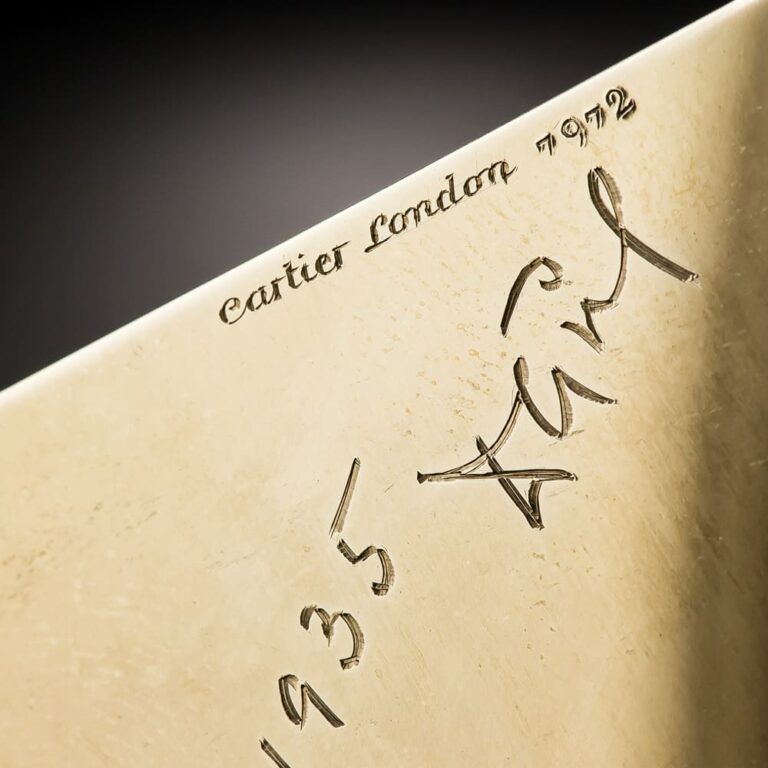

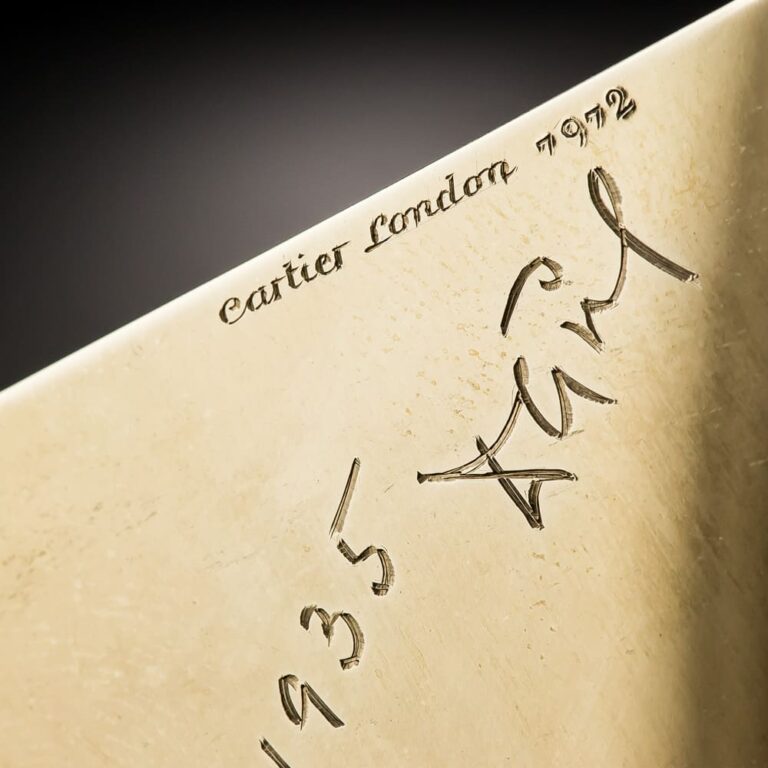

Louis and Jacques Cartier both died in 1942 and Pierre, who went on to become the president of Cartier International, retired in 1945. Cartier continued to be run by their descendants: Jean-Jacques Cartier in London and Claude Cartier in New York. In 1972, a group of investors headed by Joseph Kanoui acquired control of Cartier Paris and appointed Robert Hocq as President. Shortly afterward they acquired the London branch as well. When Cartier New York was sold in 1976, the purchasing investors appointed Joseph Kanoui as chairman and by 1979, the three separate branches were united as “Cartier World”. The world’s leading luxury group, Compagnie Financière Richemont SA, currently owns Cartier, with numerous branches worldwide. The firm continues to be known for its fine jewelry, many pieces referencing their noted design achievements from the turn of the twentieth century such as the panthere design, Santos and Tank watches and the Trinity tri-colored gold combination.

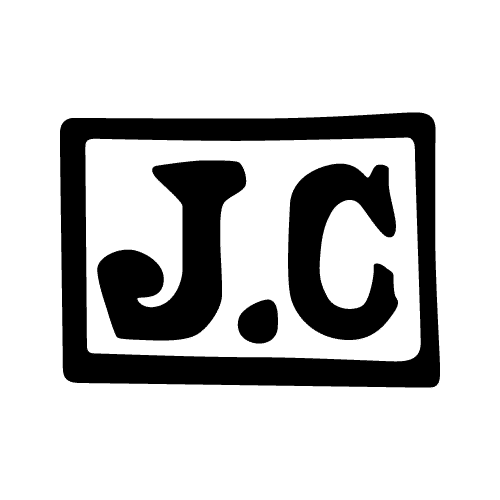

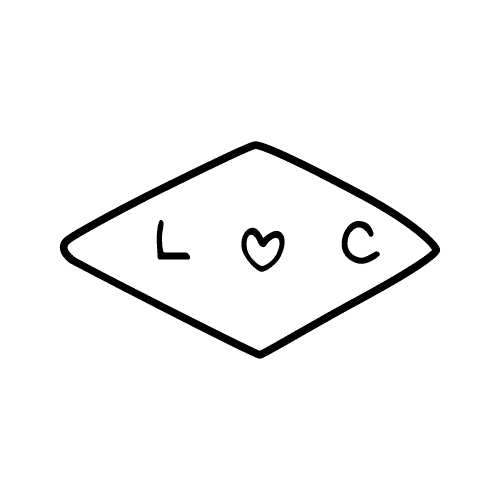

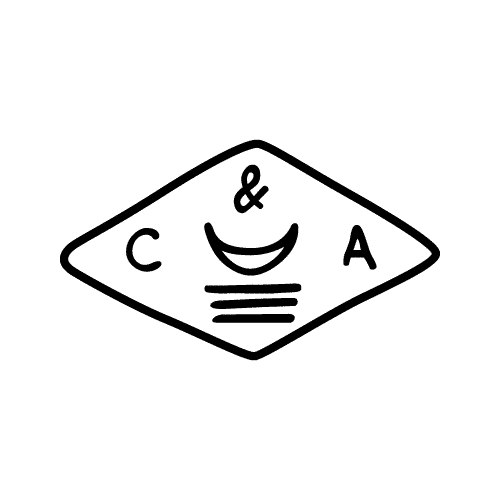

Cartier

| Country | |

|---|---|

| City | Paris |

| Symbol | cartouche, crescent, frame, heart, lozenge, moon, rectangle, rhombus, square |

| Shape | cartouche, frame, heart, lozenge, rectangle, rhombus, square |

| Era | e.1847 |

Specialties

- Famous Jeweler

1847

- Founded by Louis François Cartier.

1852

- Egyptian scarab design.

1856

- Princess Mathilde became a customer.

1872

- Son, Alfred, joined the firm.

1873

- Egyptian Revival pushed Cartier to the pinnacle of the world of jewelry.

1902

- London branch established.

1904

- Royal Warrant: King Edward VII, England.

- Royal Warrant: King Alfonso XIII, Spain.

- Queen Alexandra of England wears the Resille necklace.

1905

- Royal Warrant: King Carlos I of Portugal.

1906

- Production in the Art Deco style began.

1908

- Royal Warrant: King Paramindr Maha Chulalongkorn, Siam

1909

- New York branch opens

- Royal Warrant: King George I, Greece

1910

- Sale of the Hope Diamond

1913

- First Mystery Clock

1914

- Royal Warrant: Duke Philippe d’Orleans

1917

- Two strands of natural pearls traded for a mansion at 653 Fifth Avenue.

1921

- Royal Warrant: King Edward VIII.

1924

- Trinity Ring and Bracelet.

1933

- Jeanne Toussaint The Panther became Director of Fine Jewelry.

1936

- Royal Warrant: Prince Louis II, Monaco.

1942

- Caged Bird Jewel

1944

- Freed Bird Jewel

- Panther Brooch ordered by the Duchess of Windsor.

1969

- Cartier Taylor-Burton Diamond sold to Richard Burton.

1970

- Love bracelet.

1997

- 150th anniversary.

Currently owned by Richemont.

Related Reading

Sources

- Cartier, Incorporated. Retrospective Louis Cartier: Masterworks of Art Deco. 1982

- Chapman, Martin. Cartier and America. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and DelMonico Books, 2009.

- Nadelhoffer, Hans. Cartier: Jewelers Extraordinary. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,1984.

- Rudoe, Judy. Cartier 1900-1939. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,1997.