Introduction

Necklaces have existed ever since our ancestors began to walk upright. Our desire to adorn ourselves has been evident since ancient times with Paleolithic and Neolithic necklaces made from shells, bones, teeth, and claws found at sites of archaeological explorations. As our sophistication and knowledge grew so did the variety of materials and the level of detail and design used in jewelry. The Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, virtually all civilizations, had unique methods for designing and making jewelry, ranging from simple strung bead arrangements to more elaborate combinations of materials and patterns.

Antiquity

Ancient Egyptians favored a “broad collar” comprised of beads strung in vertical, parallel rows fashioned in a bib-like shape, tied with a cord at the back. Heavy funerary collars were created from metal sheet and chased with talismanic Egyptian motifs. Strings of beads tied in the back with a cord were worn choker style and pectorals designed as large emblematic motifs were inlaid with faience and gemstones.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

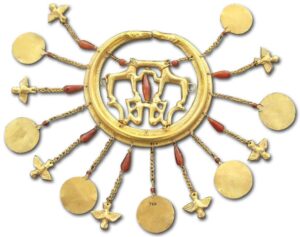

The Minoan civilization stamped out gold beads to create many different forms of jewelry. Necklaces and pendants featured beads decorated with complex granulation and repoussé. An Egyptian influence was evident in their choice of pectorals and the motifs that they created and adorned with expert use of filigree. Large gold disks with repoussé animals were often suspended from the pectorals. The Minoans were also clever chain weavers and, as a result, chains began to be worn as necklaces in their own right without the addition of charms, pendants or other symbolic motifs.

The Etruscans were the ancient world’s most accomplished goldsmiths. Fabulous necklaces included the art of chain making further embellished with a myriad of repoussébeads with intricate granulated designs. When discovered centuries later, jewelers tried in vain to emulate the fine work of the unparalleled civilization. The techniques they used for accomplishing such incredible granulated designs frustrated generations of jewelers who strove tirelessly to recreate the magic.

Classical Greek necklaces linked together repoussé motifs sometimes decorated with filigree and granulation and suspending hollow forms such as amphorae, flower buds, beads, flowers and human heads. Medallions with elaborate designs were suspended from chains featuring these incredible repoussé motifs along with swags of chain.

Discussing jewelry from the Hellenistic period under the rule of Alexander the Great, J. Anderson Black explains in A History of Jewelry: Five Thousand Years:

Rather than imposing their old designs on the newly-conquered territories, the Greeks absorbed what was best from the art of each nation and evolved a hybrid. This was undoubted the richest period for jewelry and goldwork in the history of the Aegean world. For one thing gold was more readily available both from deposits in Asia and Egypt, and from looted treasures which could be broken up and the metal re-used.1

Their interpretation of Etruscan design adapted the strap necklace but replaced the pendants with more geometric forms abandoning the Etruscan figurative motifs. More gemstones were being used and chains included finials and gold, glass and gemstone beads.

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

Roman jewelry design was of Hellenistic origin until the 2nd century A.D. when Roman jewelers began to use the technique of opus interrasile resulting in an openwork pattern in metal. They also took the art of niello and applied it to jewelry. Romans were responsible for adding a good deal of color to jewelry using colored stones polished en cabochon. Chains suspended coins and medallions and included colored stones and segments pierced with the opus interrasile technique.

Early Celtic necklaces included torcs of twisted rod or ribbon held in place by a simple clasp. Trade with other parts of the world brought them beads made from faience and amber which they fashioned into necklaces. Similar to a pectoral was the Irish gorget. Designed as a broad crescent cut from sheet metal, it was enhanced by repoussé work and finished with large disk-shaped terminals.

Scandinavian Jewelry c.6th century featured elaborate and intricate abstract themes, including their use of a technique called “chip cutting” which involved chiseling glimmering “facets” onto gold surfaces. Combining this with filigree and repoussé resulted in a hitherto unseen style. With the passing of time, simpler geometric designs emerged.

Antiquity

c.4000-300 BC Ur

Necklace with 11 Amber Pendants, 18 Amber Beads, Blue, Black and Yellow Glass Beads, with 6 Faience Pendants. c.7th Century BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Simple bead strands of stone and glazed composite material.

c.2600 BC Ur

Lapis and Gold Beads, Ur c.2600 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Gold beads added to simple bead strands.

c.2613-2494 BC Egypt

4th Dynasty Bead Collection c.2613-2494 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Gold beads included in more elaborate bead strands.

c.2323-2150 BC Egypt

Egyptian Broad Collar c.2020 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Broad Collar Rows of nearly vertical tubular beads with the lowest row suspending drops shaped like leaves or mummiforms.

c.2200 BC Minoan/Crete

Large Minoan Golden Earring. © Trustees of the British Museum

- Gold elements: discs, cylinders, bicones and globs.

c.1991-1783 BC Egypt

Egyptian Blue Glazed Pectoral BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Pectoral – large, often trapezoidal, pendant suspended from a string of beads. This evolved to become the cartouche. Bright colors and bold shapes were common.

c.2000-1600 BC Minoan

Minoan Lapis Lazuli, Carnelian and Gold "Breast" Bead Necklace c.1700-1500 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- Lotus flowers, lilies, chains and animals made of gold were common themes.

15th C BC Century Minoan/Mycenaen

Minoan Gold Chain with Repoussé Pendants c.1700-1500 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum

- Stamped from sheet: rows of beads and designs in gold, some with granulation, (including scrolls, leaves, flowers, and fruit) were mass-produced.

c.9th Century BC Greece

Late Cypriot Gold and Glazed Composition Necklace c.1550-1050 BC. © Trustees of the British Museum.

- High-quality gold jewelry with stone inlay. Casting, repoussé produced beads of many shapes. Heavy embossed collars were made of gold plaques.

c.8th-7th Century BC, Etruscan

- Beads of glass or faience with gold, silver or electrum were worn in strands.

- Embossed pendants with geometric motifs.

- Pectorals with geometric patterns.

- Swiveling scarabs were soon replaced with seals carved in rock crystal and amber.

- Mesh chains with granulated and plain gold beads.

- Gold strapwork necklaces with looped chains suspending various pendants.

- Bulla necklaces with large disks decorated with embossed motifs (popular in 7th cen. Again in 4th cen.)

- Large pendants surmounted by a tubular element for stringing included flowers, anchors, amphorae and mellons.

c.6th -5th Century BC, Greece

- Strap Necklace: many fine chains linked together suspending a fringe of pendants.

- Gold was scarce so many jewels were made in silver and bronze. All styles: earrings, bracelets, rings, necklaces etc.

- Festoons linking numerous elements to form a necklace.

- Long linked chains with animal head terminals, sometimes with glass beads.

c.300 BC, Italy

c.4th-1st Century BC, Hellenistic

c.4th-1st Century BC, Celtic

- The use of a clasp composed of a ring and a hook began to replace ribbon or string for tying a necklace onto the neck.

- Use of color in jewelry became increasingly important to the Greeks.

- Gemstones or colored glass were added to gold necklaces.

- Necklaces were worn close around the neck and tied at the back with a ribbon.

- Often multiple necklaces were worn together.

- Torcs designed as an open ring with decorative terminals or twisted ring with loop terminals.

c.1st-3rd Century AD, Roman

- Link chains with stone beads.

- Hook and eye clasp.

- Wheel motif pendants and finials.

- Colored gem cabochons in wide bezels, with pearls and gold links.

Dark Ages

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

During the Dark Ages, the tribes of Europe (Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and Lombards) employed their highly skilled armorers as jewelers. All the techniques of the earlier civilizations were known to these craftsman but it was their use of inlaid colored gemstones in a cloisonné fashion that set them apart. They rivaled even the Egyptians when creating mosaic stained glass window-style jewels. The jewelry extant from that period survived as a result of being buried with the owner, therefore, our knowledge is limited, but Celtic-style torc necklaces seemed to have prevailed.

Middle Ages

The Byzantine era and Middle Ages present a unique problem for those who study the history of jewelry; the long-standing tradition of burying jewelry along with the deceased ended and with it went an invaluable source of information for the historian. We do know that much of the jewelry produced during that period was religious in nature. Opus interrasile, filigree and cloisonné enamel were popular techniques used to enhance the many designs made possible by the abundance of gold available. Intricate pendants, necklaces composed of openwork disks and medallions all mixed with beads and pearls formed the necklaces popular at the time. Niello and enamel replaced colored stone inlay for design accents and color.

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

The poor economy and style of fashion drove jewelry in England and France out of favor during the 11th and 12th centuries. High-collared, layered tunics left little room for decorative jewelry therefore spare, functional jewelry, brooches, buckles, and belts, prevailed. During the 13th century, it was illegal for commoners to wear gold, silver, and gemstones. Royal jewelry from the period included cruciform pendant necklaces, rosaries, and elaborately decorated emblematic collars often suspending symbolic medallions. The Gothic era of the 14th and 15th centuries saw England following the French in passing a law forbidding commoners to adorn themselves with precious jewelry. Few necklaces from this era have survived and little information is available regarding their style or use.

Innovation marked the 15th century with technically more sophisticated stone-cutting, en ronde bosse enameling and a sense of jewelry as a fashion item rather than simply an indicator of rank. Necklaces were predominant at the time due to the extreme decolletage being displayed. Secular jewelry included strands of pearls and gemstones, pendants and heavy, highly decorated collars. The more transcendent religious jewelry included elaborate reliquary pendants with incredible detail and intricately constructed locket compartments, cruciform pendants and ornate rosaries worn as necklaces.

c.15th Century, Europe

c.16th Century Europe

- Collars of elaborate, entwined openwork and naturalistic designs with jewels and enamels (like those of the late medieval times)

- Higher necklines pushed necklaces up against the base of the neck.

- Simple necklaces with beads and pearls suspended pendant

- Long ribbons supporting a pendant functioned as necklaces.

- Necklaces were worn singly or in groups.

- Deep décolletage in northern Europe kept necklaces popular.

- Parures that featured necklaces as a central component became essential

- Later, high collars and ruffs necessitated long necklaces that could be worn over the clothing.

- Distribution of engraved printed designs created uniformity of style in the late 16th century.

- Delicate, openwork motifs with a central gemstone predominated.

Renaissance

Victoria & Albert Museum Collection.

The Renaissance period brought about great advances in art and architecture that spilled over to the goldsmith‘s art. Medallions and pendants produced with this new level of sculptural artistry enhanced by enamel, baroque pearls, and carved gemstones were also created with a thematic emphasis on religion. Jewelers began to travel and circulate pattern books making it difficult to definitively pinpoint a particular goldsmith’s creations and causing prototypical designs to dominate. Repeated shapes, themes, and techniques appear throughout Europe. Delicate chains with and without pendants and chokers of pearls and beads were worn by women and heavier chains set with gemstones were favored by both men and women. Massive chains whose links were weighed individually were worn by men to serve as a way to transport their wealth with the “measured” links being readily available for use as currency. Later in the period, the theme for pendants and necklaces shifted away from enseigne medallions and religious iconography to mythological creatures. Women began to display more jewelry than men.

Pearls had long been available in Europe but in the mid-16th century, due in large part to the extensive travel and trade by European explorers, they became available in much larger quantity than ever before. The result was a fashion for pearl necklaces of great length, sometimes wound around the neck several times or swagged and pinned in place across the bodice.

The seventeenth century saw the development of technology that would enable gemstones to be faceted. Necklaces were constructed threading precious stones in their settings together with ribbon. This was the germination of the necklace known as the rivière. More elaborate necklaces featured a series of cluster pendants suspended from a chain or cord and tied around the neck. Memento mori jewelry with coffins, skulls, skeletons and other macabre themes made an appearance at this time.

17th Century, Europe

- Décolletés return.

- More widespread use of faceted gemstones becoming the focus of the piece.

- Linear necklaces with closed collets.

- Short bow motif neclaces.

- Most important were pearl necklaces.

Related Reading

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Black, J. Anderson. A History of Jewelry: Five Thousand Years. New York: Park Lane, 1975.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington Dawes with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714-1830: Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Mascetti, Daniela and Triossi, Amanda. The Necklace: From Antiquity to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1997.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Jewellery in Britain: 1066-1837, Wilby, Norwich: Michael Russell, 1994. Pp.168-169.

Notes

- Black p.72.↵