Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

The French firm of Boivin, founded in Paris during the 1890s by René Boivin (1864-1917) is considered to have produced some of the most original and finely wrought jewels of the twentieth century. Well known for the impeccable craftsmanship of its pieces, the firm set itself apart by its masterly use of colored stones and by its thoroughly modern and sculptural designs. The most well-known and audaciously designed of their jewels were produced during the 1930s and 1940s when the firm was run by René’s widow, Jeanne Boivin (1871-1959), and employed the design talents of three remarkable women: Suzanne Vuilereme (later Belperron), Juliette Moutarde and Jeanne’s own daughter, Germaine Boivin.

The Founder

The firm’s namesake, René Boivin, followed his older brother Victor into the jewelry business by becoming an apprentice goldsmith at the age of seventeen. Taking drawing lessons at a local art school and mastering his chosen craft at a variety of different workshops, René quickly distinguished himself as an accomplished draughtsman, gifted jewelry designer and skilled engraver.

By 1890, he was ready to establish his own name and bought the first of several workshops in Paris, where he built up an inventory of equipment and skilled workers. A few years later he moved his firm into a new workshop on the rue de Turbigo and married Jeanne Poirot, sister of the famed couturier Paul Poirot.

Word of mouth established the firm’s reputation for faultlessly manufactured pieces of artful beauty. They manufactured designs for well-known jewelers such as Mellerio and Boucheron. Conversant in all the fashionable and classical jewelry designs of the day, René Boivin was especially drawn to naturalism. With his interest in and comprehensive knowledge of botany, many of his pieces at the turn of the century were realistically rendered and articulated floral designs. While naturalism and flowing lines were a hallmark of the Art Nouveau style, the firm of Boivin did not follow the movement. Instead, they came to specialize in more unconventional designs that were appreciated by a discerning clientele some of whom Rene and Jeanne met while attending the lavish parties of Paul Poiret. As Françoise Cailles writes:

The Boivin couple would attend these receptions, at which Paul Poiret’s own creations were naturally worn or displayed. Quite often, the acquaintances they made in these dazzling circles would later become clients. From that time onwards, the Boivin clientele became increasingly specialized, with the accent on aristocrats, artists, intellectuals, and foreign personalities. René himself gradually became known as ‘the jeweller of the intelligentsia’.1

By 1905 Boivin had virtually stopped supplying other jewelry houses and instead focused exclusively on private clients. While still producing a number of traditional pieces, many in the garland style, Boivin transcended contemporary fashion with his more original designs and choice of materials. He made frequent use of such semi-precious as moonstones, aquamarines, and pink sapphires as well as calibré cut diamonds often pairing them with more common materials. A notable example is the large style signet rings crafted in wood and pearls, transforming what had previously been a masculine article into one that was both feminine and modern. Francoise Cailles notes of his more modern rings:

The proportions were bold and the materials even bolder. He would coat the body of yellow gold rings with black enamel, using ebony, ivory, coral and sometimes vulcanite inlaid with pearls and precious stones.2

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

In 1900, well before its appeal influenced Art Deco, Boivin was creating pieces with Egyptian motifs including a striking and very large chased gold ring centering a marquise diamond flanked by two sphinxes.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Following the Egyptian style, he also created a series of jewels inspired by Mesopotamia. His subsequently named ‘Assyrian’ jewels, featured various portrayals of lions’ heads of yellow gold or gilded silver with gemstones.

More sparingly designed were the pieces that were known as the ‘Hallstatt’ and ‘Merovingian’ jewels. Boldly modern in the striking simplicity of their archetypal spirals, they did not find a sympathetic audience until many years after their initial debut.

René Boivin died in 1917 at the early age of 53. The business and his reputation for creating beautiful and desirable pieces were at their height. While it would have been expected for his wife to sell or close, Jeanne Boivin made the surprising decision to take over the firm and continue its tradition of producing fine jewels. In a resolutely male-dominated industry, no woman had ever before been at the head of an important jewelry firm. Jeanne Boivin, drawing on twenty-five years of experience running the business with her husband, must have felt that she was more than qualified to continue the firm’s operations and build upon their success. The next decades in the firm’s history stand as a striking testament to her independent nature, her business acumen, and her outstanding creative sensibilities.

Madam René Boivin

In the years 1917 to 1920, following her husband’s death, Madame René Boivin, as she preferred to be known professionally, persevered and completed already existing orders. While the firm name remained René Boivin, Jeanne Boivin gradually began to create her own distinctive pieces. Although not a designer herself, she had a strong sense of style and, after many years of working beside her husband, a depth of knowledge about how a piece of jewelry was designed and created. While all her designs were rendered by others, she dictated all aspects and details of her compositions. Departing from the more traditional and classical themes of René’s work she developed an independent style that combined a lively range of colored stones, textures, and dimensions working mostly in yellow gold. She considered a piece of jewelry as a combination of all its parts in which gemstones were but one element in the overall look and feel.

Françoise Cailles states:

She was not impressed by the ostentatious displays of gems that characterized the 1930s …a jewel was an object with its own identity, reflecting the personality of the wearer. She liked jewels to bring out the best in women, but she also liked women to bring out the best in jewels.3

Working with trusted and accomplished craftsman such as Davière her master jeweler, and the exceptionally talented lapidary, Adrien Louart, the house of Boivin produced unique geometrical and sculptural pieces innovating the combination of wood, rock crystal and hardstones with diamonds and colored gems such as lapis, citrine, peridot, amethyst and tourmalines. Boivin jewels attracted a wealthy and distinguished private clientele. The firm moved to a new salon in 1931 on the avenue de l’opera and remained known only by referral. Madame Boivin had no interest in operating a retail concern expressing the thought that her firm’s reputation for finely made and original jewels would attract sufficient business. Also notable was her reluctance to sign pieces. Françoise Cailles notes:

Twenty five years of collaboration with René Boivin had convinced her that a beautiful piece of jewelry spoke for itself;to sign it would be pure affectation.4

While most of their output was thus left unsigned there were certainly exceptions, particularly when requested by a client.

In the early 1930s, in a marked stylistic change from the geometrical Art Deco aesthetic, Boivin began to produce bold pieces with rounded silhouettes favoring spherical and elliptical forms. More naturalistic designs were also produced featuring animals of all varieties including sea creatures and once again, delicately and realistically rendered floral designs.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

This period also marked a change in Boivin’s main designer. When Jeanne Boivin first took over the firm in 1917, one of her first decisions was to hire a then-unknown salesgirl, Suzanne Vuillarme. Under her married name of Belperron, she would establish herself as one of the most talented and collected jewelry designers of the twentieth century. When Suzanne was hired in 1921, she had attended both the Municipal School of Music and Fine Arts and the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. Her background and talent were duly recognized and by 1925 she was designing models for Boivin, many in the unusual combinations of precious and semi-precious materials that would become her signature style as an individual designer. She remained at the firm until 1931. While with Boivin she was introduced to her future business partner, Bernard Hertz as well as to the talents of Louart, Cauvain, and Groëné et Darde who would be instrumental in creating and engineering her own pieces.

Juliette Moutarde who replaced Suzanne would remain with the firm until her retirement in 1970. She had trained as a jewelry designer and developed a close working relationship with Jeanne Boivin. Françoise Cailles writes:

…the two women complemented one another perfectly; one gave shape and substance to the ideas of the other-who then minutely supervised the manufacture of the finished article down to the very last detail.5

Germaine Boivin joined the firm a few years later in 1938 as a designer and continued to run the firm after her mother’s death in 1959. In 1976, she sold the firm to Jacques Bernard, a Boivin designer who had joined the firm in 1964 and who continued to produce pieces within the Boivin tradition. The firm was sold to the Asprey Group in 1991 and at some point later, the decision was made to close the house of René Boivin.

Jewelry Highlights

Brooches

A wide range of geometric brooch shapes was produced by the firm. Shapes introduced in the twenties through forties included: Plaques that often used step-cut rock crystal as the central body; Rounded Discs also featuring tiered layers of crystal accented with pave diamonds and calibre-cut gems; Arch brooches first created by Juliette Moutard in 1933 and designed to project from the wearer’s garment; Shield-shaped brooches and Escalier brooches crafted from carved pieces of rock crystal, smokey quartz or onyx.

During the thirties, most French jewelers continued in the geometric vocabulary of the Art Deco movement. The house of Boivin was an exception and, concurrent with their more abstract designs, they produced figurative and naturalistic themed jewels. The three most famous of Boivin’s floral designs are orchids, foxgloves and umbel clusters. René Boivin designed the first orchid brooch in 1905 while Juliette Moutard created the foxglove design in 1944. The delicate and intricate platinum and diamond umbel clusters were based on a design by Germaine Boivin and worn often by her mother. By the 1940s, the designs became more stylized and larger in scale often featuring important center stones such as the 35 carat sapphire centering a yellow gold and canary diamond leaf brooch.

The 1950s and 1960s employed both stylized and more natural replicas. The cedar tree brooch that Germaine designed for her mother’s eightieth birthday is a lovely example of both design aesthetics and showcases Boivin’s wide color palette. Fruits were another popular motif starting with the first cluster of pearl gooseberries in the 1920s and continuing with pomegranates, raspberries, pineapples and large clusters of grapes all worked in gemstones of various colors and mostly executed in warm shades of gold.

Photo Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

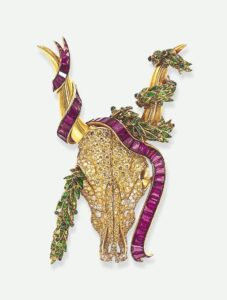

The house of Boivin created a number of different animals including the chameleon brooches that could rotate color with a push of their tongues as well as all manner of winged creatures, horses, elephants, tigers and fantastical mermaids. One of the most well-known designs is of a pigeon’s wing designed in 1938 by Juliette Moutard that features delicately colored calibré cut buff top sapphires and pavé diamonds. From ethereal to surreal, the same year saw the creation of Germaine Boivin’s famous avant-garde longhorn brooch created for a Texan who brought in a cattle skull from which to commission a jewel.

The most famous and iconic of Boivin’s pieces, however, is a starfish brooch created for the actress Claudette Colbert in 1936. Designed by Juliette Moutard, the brooch was notable for its large scale, ruby and amethyst camaïeu color scheme and life-like articulated arms; a thoroughly unique and modern piece of jewelry.

Rings

When Jeanne Boivin took over the firm, she decided to stop production of the more traditional claw settings to focus on producing larger, and bolder pieces such as the large signet rings so associated with the Boivin name. Many of their rings featured a range of unusual materials and techniques. Rings made of carved rock crystal, quartz, amethyst, citrine and agates set with contrasting gemstones were a specialty of the firm. In what must have been a striking combination, Cailles mentions that the first of their carved hardstone rings was of rose quartz set with a large yellow sapphire. Another fine example is their signature ribbed “bibendum” ring first produced in 1928. In addition to using carved hardstones, Boivin created rings of other unique materials such as grey gold, black lacquered platinum, red enameled gold, and of course woods such as ebony and sandalwood. The fish scale motif featuring scalloped rows of stones set in yellow gold debuted in 1925 and became a recurrent theme, extending to necklace and bracelet designs as well. Of the later designs, two are particularly renowned. The “Quatre-Corps” ring first designed in 1950, is a lighter design featuring four rows of graduated bezel set stones, usually semi-precious. The other is the “Pampilles” ring designed in 1956 that features a large center stone surrounded by a hanging border of smaller contrasting stones.

Bracelets

Again, sculptural, daring designs characterized most of the bracelets produced by the house of Boivin. Both the “escalier” and “bibendum” appeared as bracelets. The popular “melon slice” cuffs, so named for their curvature, are considered another of Jeanne Boivin’s iconic designs and were first produced in 1931. These bracelets were created in a wide variety ranging from simple cuffs of gold studded ivory to elaborate creations of carved stone set with diamonds and cabochon cut gems.

The “tiara” and “torque” cuff bracelets designed by Juliette Moutard in 1933 are some of her first creations for the firm and are both fine examples of Boivin’s clean, modern, and forward-thinking jewels.

Necklaces

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

While the firm produced a number of more traditional Art Deco style sautoirs, the balance of their neck pieces were designed as wide chokers or bib style necklaces. A variety of hardstones and gems enhanced their creations which were generally large in scale and referenced a number of styles including a necklace of “bibendum“ discs of carved rock crystal centered with diamonds, generously proportioned torsade style chokers of gem beads such as sapphires, and rigid bands of gold hoops terminating in clusters or rows of precious stones or pearls. Yellow gold necklaces without any gemstone embellishments were also a hallmark of Boivin.

As Françoise Cailles notes:

Madame Boivin also inaugurated a new trend in jewelry by designing yellow gold necklaces, a genre which she monopolized for many years. These chokers, worn tightly around the throat, were sometimes decorated with pendants. They featured a variety of motifs: “Assyrian”(1927), “Etruscan” (1928), gold wire coils (cannetilles, 1933) and “urn links” (1934).6

Earrings

Boivin produced both pendant-style drop earrings and an incredible range of ear clips that hugged the lobe. Drop earrings were made in four main styles: long pendant style drops dating back to the 1920s, more complex chandelier style earrings often featuring end clusters of briolettes or tassels of diamonds, hoop earrings featuring drops of hoop forms or more classic single hoop styles interpreted in modern combinations of materials such as platinum, rock crystal and diamonds, and pear-shaped pendant drops in a wide range of styles and materials.

Boivin’s clip earrings echoed all their major jewelry motifs including geometrical jewels, floral designs of colorful stone combinations and sea creatures and shells both realistic and whimsical. Some of the most regularly produced designs were wing-shaped ear clips that extended to the upper part of the ear, crescent ear clips that extended to the lower part of the lobe, gooseberry ear clips with their iconic clusters of pearls or gemstone beads and perhaps most striking to the modern eye, multiple hoop earrings that were first created in 1934. These featured a row of hoops extending up the ear that appeared as separate piercings but were, in fact, a single clip joined by a thin metal clasp hidden behind the earlobe.

Maker's Marks & Timeline

Boivin, René

| Country | |

|---|---|

| City | Paris |

| Era | e. c.1890 |

René Boivin

Specialties

- Use of Uncommon combinations of materials: i.e. wood and pearls

- Bold use of colored gemstones

- Large bold striking designs

Sources

- Cailles, Françoise. René Boivin: Jeweler. London: Quartet Books, 1994.

- Raulet, Sylvie. Jewelry of the 1940s & 1950s. New York: Rizzoli, 1988.