Peter I reigned as Russian Tsar (1682-1720) an d the first Emperor of Russia (1721-1725) earning the sobriquet Peter the Great. Peter envisioned a modern capital for his beloved Russia that would embrace contemporary Western culture, seeking to align Russia on an equal footing with advanced world powers. On May 27, 1703, Peter the Great founded the Russian city of St. Petersburg on the site of a captured Swedish fortress. Eponymously, Peter chose the apostle Saint Peter to supply the moniker for his dream city.

Peter began a series of reforms initially affecting only the upper echelon of Russian society. In order to realize the plans he had concocted for the modernization of Russia, Peter recruited shipwrights, engineers, and doctors from across Europe. He built his great city on the Neva River, styling everything from its architecture to its fashions in grandiose imitation of the West. Luxury and extravagance were the watchwords of the day and every aspect of noble life in St. Petersburg was designed to reflect this new precept. The opulence of Russia during the Romanov Autocracy was no accident.

Peter the Great was also the brains behind Russia’s jewelry superiority. Along with experts in all things Western, he seduced craftsmen skilled in jewelry and luxury goods to join his efforts. He gathered prisoners of the Scandinavian wars who possessed the necessary skills and conscripted Russian jewelers from Moscow’s Kremlin Armory. German, Swedish, Francophone Swiss, and eventually, French (Huguenot refugees) joined the efforts. Newly instituted stipulations for Western-style raiment left the women of St. Petersburg with a lot of bodily real estate on which to display their wealth. This was accomplished by flaunting increasingly elaborate jewels. Feeding this demand, it didn’t take long for the quality of St. Petersburg’s jeweler’s output to surpass that of the leading Maisons of Paris. The European craftsmen prospered under the Romanovs.

At the turn of the 19th century, a Swedish guidebook proclaimed:

nowhere do [foreign craftsmen] live … as well as they do here, since nowhere can they earn as much and as easily. 1

While Peter’s interest in jewelry was merely tangential, his successors were rabid jewelry lovers. Their passion for diamonds and other gems was voracious. Rivalry for jewelry superiority was rampant. By the time of Catherine the Great’s reign in 1762 diamonds were the dominant gem. Establishing a diamond room to accommodate her growing collection, she proudly displayed the Orlov Diamond, a 190-carat behemoth, outweighing any other known diamond at the time.

Peter the Great’s aspirations for his empire also included exploiting the natural treasures waiting beneath Russia’s vast lands to be exposed. He began to focus on the Ural Mountains and Siberia where riches not only in gemstones but in gold and platinum were ripe for discovery. This eventually freed his St. Petersburg jewelers from dependence on purchasing elements for their creations from wider European sources and thus served to enhance the already monumental wealth of the Empire.

Circa 1714, the immigrant jewelers formed the “Amt der löblichen Gold – und Silberarbeiter in Sanct Petersburg” guild. Peter became a fan of guilds and organized other trades. Already regulated, the sale of precious metals was bound by rules and laws. Russian jewelers and merchants could only do business on the “silver row.” Samples provided by prospective sellers were assayed and stamped before approval to sell was granted. Determining who could be a guild member relied on years of training and experience as a journeyman, which were two of the criteria. The quality of their work was closely monitored and anything substandard was destroyed. These qualified masters had to maintain and house any apprentices. A 12-hour workday and Sundays and Church holidays were strictly enforced. On the other hand, discipline and order were maintained at the end of a whip.

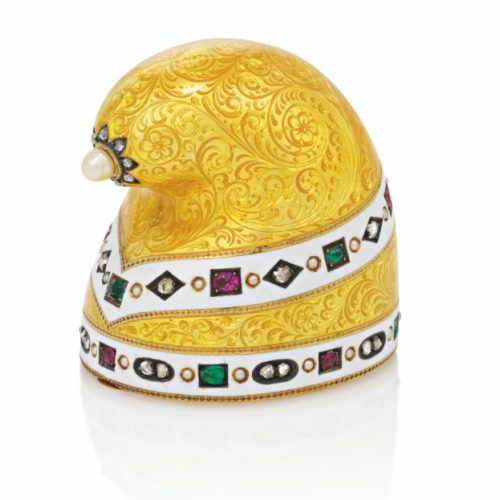

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Favored tradesmen were awarded special designations by the Romanovs permitting them to publicly advertise their relationship with the court. Initially, these honors were bestowed at the whim of the Tsar. During Alexander II’s reign, the Ministry of the Imperial Court created a standard procedure to award the designation. 1 Eight to ten years of dealing with the Court (with pricing being favorable to the court) were required to even apply for the right to display the title “Purveyor to the Imperial Court” with the double-headed eagle. This honor was awarded to an individual, not the firm, and could not be inherited and lasted only for the reign of the bestower. While this coveted designation was parsimoniously distributed about half of those applying were granted (and only after verifying their “commercial and moral aspects” with the local police.) Grand dukes and duchess also named their purveyors and while those selected by the emperor or empress could display the imperial eagle those appointed by others could use only the purveyor’s initials. The bicephalous Romanov raptor was also allowed to be displayed by winners of prizes at trade fairs thus complicating the matter of who was a purveyor to the Court and who was simply a prize winner.

The most vaulted title bestowed was “Appraiser to the Cabinet of His Imperial Highness.” Initially, only two were granted this title. In the early nineteenth century Nicholas I appointed three of them, granting the honor of advising him without pay. They did get priority when it came to commissions, but their work on repairs and other jobs for the Court were compensated only by the prestige of their title.2

Of the myriad objects commissioned by the Court, many were destined to be bestowed on deserving subjects and foreign dignitaries. For example: ”Emperor Nicholas II distributed 2,000 gifts of jewelry worth 500,000 rubles every year, from a gem-encrusted portrait miniature costing 16,000 rubles to thank a senior minister upon his retirement to a 20-ruble silver pocket watch bearing the double-headed eagle he might present to a deserving coachman or peasant who had performed some minor service.” 3 These Imperial gifts were an accolade of diplomacy as well as a lavish perk to officials for excellence in the execution of their duties to the Court. According to Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm:

These rewards were presented… to create bonds of loyalty between the ruler and those who served in his name, as well as to promote efficiency and zeal in the carrying out of one’s official duties. They were compensation for services, both political and administrative, rendered to the state.4

Peter the Great is credited with transforming imperial gift presentations from the prior system of awarding gold, fur, and land to honorees, to a more modern Western style. The European custom of awarding miniature portraits in precious metals and gems became the highest honor bestowed during his reign. His system of ranking an individual’s (earned) status remained the standard until the Revolution. Nicholas I used Peter’s “Table of Ranks” to define his presentation gifts. “Medallions, rings, and snuffboxes with his portrait were meant only for those who had attained at least the third chin (lieutenant-general or privy councilor in the bureaucracy). Even here the value could vary widely.” 5 Gifts to the lower ranks were accented by State emblems and the like. These “ordinary gifts” were rings, cuff links, tie-pins, earrings, and brooches. Cigarette boxes were added to the list circa the fin-de-siècle. Watches were another popular item with the awarding of gold watches with the eagle displayed for high-ranking officers to silver versions for the lower ranks. These were awarded for meritorious service, participating in various performances, service to the Tsar and his family by crew members on the imperial yacht, and other services.

In order to determine how their service was perceived by the Court, those receiving an award typically had it appraised and often traded the item for cash. Oddly enough, returning the item for its cash value (minus a 10% donation to charity) was regarded as totally acceptable. Often these items were recycled to a new recipient and frequently more than once. The creation of these gifts was spread around to recognized “purveyors” but some items were farmed out to smaller firms. No one firm completely dominated any particular type of item with the exception of the house of Paul Buhré who manufactured 95% of presentation watches for Nicholas II.

The Cabinet of His Imperial Highness ordered gifts from a variety of jewelers. At the turn of the 20th century, among the major workshops in St. Peterburg that furnished it were Blank, Bolin, Butz, Fabergé, The Grachev Brothers, Hahn, Ivanov and Köchli, while in Moscow the silversmiths Khlebnikov and Ovchinnikov were also suppliers. Although it helped, having the status of purveyor to the imperial court was not obligatory, and the cabinet also turned to smaller firms such as Tillander.6

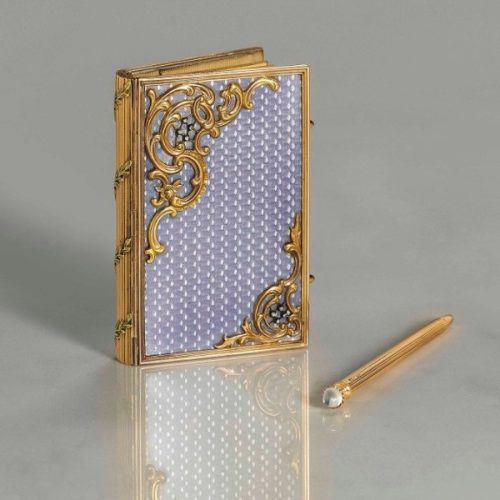

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Once again drawing from European tradition, Peter created The Order of St. Andrew modeled after England’s Order of the Garter. This knighthood, Russia’s most prestigious, was bestowed only by the reigning ruler. This became the most esteemed knighthood in Russia awarded exclusively on the basis of merit, the Emperor himself only became a member after taking two Swedish ships on the Neva River. An honor for the service of women to the Emperor was eventually established. The Order of St. Catherine (named for his wife) was created after she successfully gained his release from Turkish captivity. 6 The Order of St. George, a knighthood for military merit, and The Order of St. Vladimir for military and civil service followed under the reign of Catherine II. Further knighthoods were adopted from other kingdoms; Order of St. Anne from a German State and the White Eagle and St. Stanislas from Poland (after Russian Rule prevailed.) Each of these knighthoods provided a symbolic badge with specific instructions as to how and when it should be worn. They were displayed on all manner of goods by those who earned the privilege. Most were gem set with fine enamel and precious metals, but paste examples existed as well. Manufacture of these awards also provided a steady stream of orders to the already busy jewelry workshops in St. Petersburg.

Throughout Europe, International Exhibitions were being held to show the world the wonders being invented and created for their consumption. Russia was no exception, holding National exhibitions originating in 1829. Jewelers and silversmiths readily adopted this trend in order to market themselves on a broader stage. Securing a place to demonstrate their wares was a boon to all Russian merchants, but especially to the jewelry trade. Held every two years throughout the nineteenth century, these exhibitions featured the best that Russia had to offer. State-sanctioned artisans were also allowed to participate in other European and American exhibitions. Russian goods drew the highest praise wherever they were exhibited.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 the question became “… do the victors destroy all remaining symbols of the despised former realm. Or do they sell them?”7 In 1914, just prior to Germany’s declaration of war on Russia, the treasures at the Winter Palace were packed and shipped to the Kremlin to prevent the items from becoming the spoils of war. Throughout 1915 trainloads of valuables made their way from St. Petersburg’s palaces to the Kremlin Armory. When the Revolution of 1917 took place there were over 2000 containers of Imperial valuables in the Armory. After a lengthy and exhaustive inventory process, it was decided that items belonging to museums could be returned. Following a subsequent inventory, it was decided to exhibit the Russian crown jewels in Moscow. Over 400 items were on view for only the second time in history. In 1927 Stalin’s regime began to sell the jewels, this sale dragged on until 1936. Various inventories, auction catalogs, court appraisals, and other photographs and documents have served as the historical record for this vast treasure. Russian ojets d’art and jewels still draw a crowd with buyers and collectors hungry for these amazing creations.

Sources

- Betteley, Marie, and Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David. Beyond Fabergé: Imperial Russian Jewelry. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing LTD, 2020.