The romantic movement which arose during the second half of the 18th century as an antidote to the Enlightenment came to full blossom during the first part of the nineteenth century, a period we generally describe as Early Victorian or the Romantic Period in the English-speaking parts of the world. Even when the Victorian era really started around 1830 (1837 if one wants to be historically correct), one can see its roots starting to develop in the late 18th and early 19th century – especially from around 1815. Where The Enlightenment movement looked at nature from a rational viewpoint, the Romantic fervor placed emphasis more on inner emotions which were hard to describe by those who experienced them. It was a fusion of awe, loving sentiment and smallness toward history and nature. Naturalism on a pedestal if you will.

You are as slender as this clove!

You are an unblown rose!

I have long loved you,

and you have not known it.1

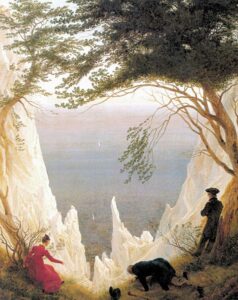

In visual arts, the Romantic movement is easily recognized in works by Caspar David Friedrich, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. The terrors and vast ship of nature are expressed in dramatic sceneries of shipwrecks, cliffs and woodland panoramas. Man always – happily – needing to obey the forces of a stronger hand. The literary works of the German writers in the Sturm und Drang movement helped shape the mindset of the early Victorian middle and upper classes. In Goethe’s, almost autobiographical, “The Sorrows of Young Werther” we can read about the foolishness of youthful lovers and their desire to self-destruct. Werther, enchanted by the betrothed Charlotte, tortures himself by staying near his unanswered love and her – more than understanding – fiancé with an almost inevitable result. Distant admirers, as there will always be, seek confirmation in all they can find, however small the gesture. In music, this suffering genre is of course based on strong minor modes.

Do you remember the flowers you sent me, when, at that crowded assembly, you could neither speak nor extend your hand to me? Half the night I was on my knees before those flowers,

and I regarded them as the pledges of your love; but those impressions grew fainter, and were at length effaced.2

It seems almost natural that in the light of attempting to describe their most inner feelings – which could now be expressed openly – the Victorians were on a quest for symbolism. In jewelry, this had already developed in the early 19th century in the form of regard type jewelry where a text was spelled out with gemstones. One could, for instance, spell the word “regard” by lining a row of gemstones as follows: “Ruby-Emerald-Garnet-Amethyst-Ruby-Diamond” and the receiving party would be able to decipher the meaning from it. The Weeping Willows themes in mourning jewelry which were used since the late 18th century also belong to this category. From around 1830 it became popular to “say it with flowers” as a florist advertising would say. Emblematic meanings were given to almost any flower inhabiting the vast amount of gardens and this language was well understood to every class in society. This fashion in jewelry had its zenith between 1830 and 1850 in England – up to around 1880 in the USA. Even today we assign emotions to flowers, even when in a slimmed version.

The emblematic meaning of flowers was already known to the ancient Greeks but have found their way to medieval Europe during the times of the crusades and were used during the Renaissance as well as during the early Baroque. The horticultural style between 1650 and 1700 is a good example of this. It was in the first half of the nineteenth century that it became a craze, inspired by the published works of Lady Mary Wortley Montegu (1717 – published 1763), Aubry de la Mottraie (1727) and Louise Cortambert (1819).

Lady Mary Wortley Montegu resided, as the spouse of the English ambassador to Turkey, in Constantinople (Istanbul) during the latter years of the 1710s where she was introduced to the rich cosmopolitan culture of the Ottoman Empire. The letters she wrote during her stay were later published in print as the “Turkish Embassy Letters” and they reveal the secret language of flowers as practiced by the ladies in the harems and the billet-doux3 in nosegay form by servants and slaves in order to keep their thoughts unspoken, yet conveyed to the object of their desire. Much as the Capoeira dances from Brazil or the colors attributed to the Suffragette movement.

This exotic language of flowers was mnemonic in character rather than the emblematic meaning Victorians gave to the various flowers. In order for the message to be understood, one used a flower (or other object such as fruit) to be handed out. This flower – or fruit – rhymed with a small message. When one would want to send the message “do not despair”, handing a pear would be enough for the message to be understood. In the Turkish language it would say “Ermut, Ver bize hir umut” (Pear, give me hope) where ermut rhymes with umut3 which has the same general meaning as the English version. This mnemonic language was reported again a small hundred years later by Baron Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall in his “Sur Le Langage des Fleurs” in 1809. Von Hammer learned this secret harem language from the Greek and Armenian women who had access to the harems, and who helped him translate it into French. Due to the lack of a proper Turkish dictionary the aforementioned popular phrase got translated to “Armoude, Wer bana bir Omoude” (Pear, let me not despair) – published in various varieties. Both the words armoude and omoude do however not exist in the Turkish language. Armoude would have been a phonetic of ermut (pear) and Omoude that of umudunu (meaning “despair” when used as umudunu kesmek). The postscript “Biber” (Turkish for pepper) rhymed with “haber” (news) and would mean “send me an answer” (Biber, Bize bir dogru haber). This hieroglyphic language is named selam or salaam, a Turkish greeting.

Needless to say that this salaam language was secret among two people or a group of people as the code would have been easily deciphered by the guards or master otherwise. This in high contrast to the Victorian language of flowers as described in 1819 by Louise Cortambert in her “Le Langage des Fleurs” – translated into English in 1820 by Shoberl – where the flowers were given an emblematic meaning. As an example, a rose would mean “love” (openly expressed) while a red tulip would mean a confession of love. The calla lily was given the definition of “magnificent beauty”, a clover “think of me” and one can only imagine to whom the calla lily and clover locket once belonged to. The many books on this subject produced extensive lists of flowers with their attributes and most Victorians would have understood the meanings. It is therefore not very plausible that a gentleman, trawling through the park, would hand an engaging lady a nosegay to express his sentiments while her spouse was present. That would be akin to the modern version of sending a lady at the opposite end of a bar a drink, it transmits an unmistakably clear message that everyone understands.

Often the flower bouquets were arranged in a specific order to read a whole message. One such message reads “May maternal love protect your early youth in innocence and joy!4 and the recipe would be:

- Moss – Maternal love

- Bearded crepis – Protect

- Primroses – Early youth

- Daisy – Innocence

- Wood sorrel – Joy

Language of Flowers

| Flower | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Acacia | Secret Love |

| Amaryllis | Pride, Splendid Beauty |

| Aster | Reciprocity |

| Azalia | Adoration |

| Begonia | Deformity |

| Buttercup | Childishness |

| Calla Lilly | Magnificent Beauty |

| Crocus | Abuse Not |

| Daffodil | Regard |

| Dahlia | Joy |

| Daisy | Innocence |

| Forget-Me-Not | True, Undying Love |

| Gardenia | Peace |

| Gladiolus | Ready Armed |

| Hyacinth | Sorrow |

| Iris | Message |

| Ivy | Friendship |

| Jasmine | Amiability |

| Lavender | Distrust |

| Lily of the Valley | Return of Happiness |

| Lotus Flower | Estranged Love |

| Magnolia | Love of Nature |

| Marigold | Grief |

| Narcissus | Egotism |

| Orchid | Beauty |

| Primrose | Early Youth |

| Red Rose | Love |

| Red Tulip | Confession of Love |

| Sunflowers | Adoration |

| Violet | Faithfulness |

The language of flowers was an important one in jewelry – and daily life – through most part of the nineteenth century and some of it has been handed down to us, although there is room for a romantic renaissance.

Sources

- Baron Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, “Sur le langage des fleurs”, Fundgruben des Orients, I, Wien, 1809, p. 32-42;Jenaische allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung 1810, dritter band (Julius, August, September). Jena, Germany

- Understanding Jewellery, Bennett & Mascetti, David & Daniela. Antique Collectors’ Club. ISBN 1851490752

- Twee eeuwen sieraden, Huibers, Jef. Vakschool Schoonhoven

- Le langage des fleurs, Mme. Louise Cortambert (Charlotte de Latour), 1819. Translated by Frederic Shoberl, 1820.

- Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague: Written During Her Travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, to which are Added Poems by the Same Author (“Turkish Embassy Letters”), Lady, Mary Wortley Montagu.

- Language of Flowers, Kate Greenway – 1884.

- Vanity fair, William Makepeace Thackeray – 1848. ISBN 1603037810

- The sorrows of young Werther. Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. 1774.

- The Language and Sentiment of Flowers. McCabe, James D. Applewood Books. 2003. ISBN 1557093849

- Romero, Christie. Warman’s Jewelry. Iola, WI, USA: Krause Publications, 2002