The First Fifty Years 1771-1825

Photo Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Following the Revolutionary War, newly independent Americans began to look beyond Great Britain to the wider world for resources, goods, and products. Trade with other parts of Europe grew and soon America was filled with new ideas. These new ideas and designs were filled with symmetry, geometry, and delicate ornamentation. Americans embraced the style and made it their own. Over time, it has become known as “The Federal Period.”

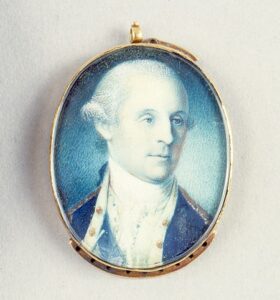

During the first few decades of independence, jewelers in the newly formed United States created an immense amount of mourning jewelry, hairwork, portrait miniatures and gold beads. Craftsmen from all corners of Europe, immigrating to America, brought with them the skills necessary to produce jewelry as fine as any made in Europe. Portrait miniatures and inscriptions with religious or personal messages were a prominent theme. Not wanting to seem pretentious and desiring to set the “American” style, prominent people of the day opted to appear fashionable albeit with a good deal of restraint.

The fine art of miniature painting had evolved into a jewelry necessity by the early part of the nineteenth century. Having the portrait of a loved one to keep you company during long absences became significant. New materials such as ivory emerged on which the portraits could be painted. Artists provided the miniatures to the customers and jewelers provided the framing or setting. Miniature artists were in great demand although there were very few of them to be found in America. Consequently, when traveling abroad a popular pastime among Americans was to have their miniature painted by an established artisan. See the portrait of Jeremiah Lee below.1

c.1777.

Artist: Charles Willson Peale

(American, 1741–1827)

The first President of the United States was painted in miniature on several occasions. Noted American artist, Charles Wilson Peale, painted a miniature portrait of George Washington in 1777.2 Washington was immortalized in miniature once again in 1789 by Irish born artist John Ramage (1748–1802). Ramage mounted the miniature himself in a handmade scalloped case.3

The early portraits were oval with engraved cases, evolving into a more circular shape with more elaborate decoration. Ivory miniatures had originally been constrained by the size of the tusk the ivory was cut from but in the nineteenth century, the tusks began to be cut on the bias allowing for larger portraits.

These portable portraits were worn in a variety of ways. In the countryside, it was popular to suspend the miniature from a ribbon around the neck. They were also fashioned as a brooch to be worn over the heart, sometimes face down. They could also be set in a ring as a memorial or funeral remembrance as in the portrait of George Washington in the picture to the right. Miniatures were also commonly mounted as clasps on bracelets. Martha Washington is said to have worn two bracelets, one on each wrist, with a portrait of her son on one and her daughter on the other.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The practice of exchanging eye miniatures, a miniature portrait of only an eye and recognizable only to the recipient, grew in popularity. This custom is believed to have begun in the late Eighteenth Century with George IV prior to his coronation. In order to keep his romance with Maria Fitzherbert, a widow, secret from the disapproving court, an eye miniature was conceived of and painted by a court miniaturist. These very personal love tokens are very rare and highly prized.

Hairwork was also a popular way to memorialize a loved one. During the eighteenth century, hair was woven or braided and placed on the back of a miniature under glass. Skilled artisans devised ways to make intricate and elaborate designs and hairwork began to move to the front of lockets, brooches etc. as a design element, not just as a memento. Sometimes the loved one’s hair was actually dissolved into the paint to be used in the illustration of a portrait miniature.

Hair could be provided by the customer and/or from the person to be memorialized or remembered. Sometimes the loved one’s hair was actually discarded and hair on hand was substituted. Eventually, advertisements to purchase long hair began to appear in the local papers (brown and black preferred) and ready-made hair jewelry could now be manufactured and purchased. To prepare for use, the hair was curled and blended with filigree to form intricate designs. Coils of fine gold thread were spooled and used as decorative elements with the hairwork. Seed pearls, and occasionally gemstones and enamel, also enhanced these miniature works of art.

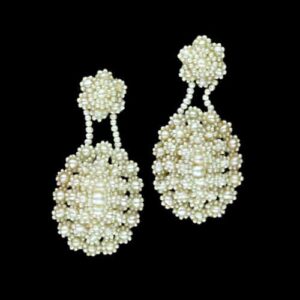

Seed Pearl jewelry remained in high demand with Americans even after its popularity waned in Europe. Parures made from seed pearls were a much sought-after wedding gift for brides. This bridal jewelry often included a pearl tiara, necklace, and earrings. Hundreds of tiny seed pearls were strung on horsehair and attached to mother-of-pearl templates to form complex designs. Rosette earrings composed of one rosette worn on the ear or two rosettes suspended top and drop style, were very popular. Pearl-strung hoop-style earrings were also fashionable.

Topaz was a favorite gemstone during this period, especially yellow-colored topaz. Although citrine was sometimes substituted for topaz, whether by accident or design, it was the yellow-colored gem set in yellow gold that was desirable. Amethyst and aquamarine also enjoyed widespread regard.

During the American Revolution, and for some time afterward, diamonds had waned in popularity, considered extravagances that were unattainable to most people. By the beginning of the nineteenth century though, demand for diamonds had picked up a bit and items such as diamond shoe buckles enjoyed a resurgence. Following suit, there was a modest revival in diamond fashion paste as well as paste items such as pins, buckles, and combs foil-backed to imitate the extremely popular topaz.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

Wedgwood plaques with classical motifs in relief, sometimes called jasperware, became the first mass-produced “costume jewelry.” These green, blue or lilac plaques were usually mounted in cut steel, but occasionally gold or silver. Cut steel jewelry became popular in France after the Revolution as the wealthy had turned in their fine jewelry to the national Treasury. Americans embraced the trend for cut steel jewelry wearing it in every form for every occasion. Iron jewelry was also found in American jewelry wardrobes although not as often as in Europe.

A wide variety of gem materials were found in the jewelry worn by American women, who took their cues from the trends in Europe. Amber, popular in Europe was imported to the United States with some success. Coral beads also found their way to America from Italy through England. Native Americans had also begun to include coral in their jewelry. Carnelian was used in combination with pearls or carved as intaglios and seals and carnelian beads were very popular strung as necklaces. Jet jewelry marketing increased with the introduction of the lathe c. 1800. Imported to America, it was popular for mourning and often included a compartment for a hair remembrance. Shell carved as cameos, buttons, and beads, very often with classical motifs, was an art revived in Italy and encouraged in popularity by Empress Josephine in France.

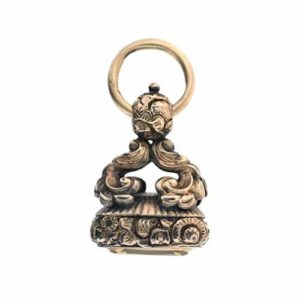

During this period our reliance on Europe for watches lessened. The parts necessary for watch manufacture could be produced in America making watches more affordable to the masses. Soon a watch and all of its requisite trinkets became a must-have item for American gentlemen. Watch chains, fobs, seals, and keys, etc. grew in popularity as watch ownership increased. Women too wore watches, often as part of a chatelaine that suspended other useful household items such as keys, needles, thimbles, ivory note cards, pencils, and seals. Watches could also do double duty as items of remembrance having portrait miniatures and locks of hair as a part of their decorative elements.

Photo Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum Collection

Gentlemen were limited in the jewelry they could wear – cuff links, shirt studs, buttons, buckles, rings, stickpins, and watches. The introduction of “Societal Jewelry” allowed for more flexibility in gentlemanly adornment. Emblems representing various societies were created, often in Europe, and worn by the members. Fraternal societies began to flourish and with them came medals, jewelry, and watches with emblematic decorations. Masonic jewelry, designed with motifs of stonemason’s tools and architecture, representing truth, beauty, and nature, began to be made in America and not just imported. Phi Beta Kappa keys and, medals for members of that elite group were also first worn during this period. Similarly, military medals, fancy swords, epaulettes, etc. were jewelry items considered acceptable for a gentleman to wear. Following the War of 1812 military dress became very elaborate and uniforms were decorated with silver and gold thread, buttons, and buckles.

Designed primarily in yellow gold with pearls, delicate patterns and festoons were popular. Designs with patriotic motifs began to appear in jewelry, especially the bald eagle, alongside traditional motifs like doves, fruit and classical figures. Topaz and amethyst continued to be preferred gems, with amber, coral, jet, and carnelian joining them. Enameling began to take on color, royal blue and emerald green joined the previously monotone black tracery. Enameled and engraved oval and rectangular-shaped clasps were in fashion. Classical figures reappeared on cameos and Wedgwood plaques.

New techniques in jewelry-making appeared during this time. Rolled gold plate was now available as a jewelry-making material and factory operations for the mass production of jewelry had begun. This ability to make jewelry for the masses helped spread the new American style throughout the young country.

Timeline: Part II

| Name/Period | Year | Company Info | Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph Cooke Philadelphia PA | c.1784 |

|

|

| James Jacks Philadelphia PA | 1797-1800 |

|

|

| Nehemiah Dodge Providence RI  | 1794 |

|

|

| Galt Bros. Washington DC | c.1800 |

|

|

| Maiden Lane | Early 1800s |

| |

| Epaphras Hinsdale E. Hinsdale & Co. Taylor & Hinsdale Newark NJ  | 1801 |

|

|

| Jabez Gorham (1792-1869) Providence RI  | 1906 |

|

|

| Fletcher & Gardiner Boston MA Philadelphia PA   | 1808 |

|

|

Jabez Baldwin | 1813 |

|

|

| Samuel Kirk Samuel Kirk & Son Co. Market Street Baltimore MD  | 1815 |

|

More American Jewelry

Sources

- Dietz, Ulysses Grant; Joselit, Jenna Weissma; Smead, Kevin J.; and Zapata, Janet. The Glitter & the Gold: Fashioning America’s Jewelry, Newark NJ: The Newark Museum, 1997.

- Fales, Marthy Gandy. Jewelry in America 1600-1900: Woodbridge, Suffolk England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1995.

- Price, Judith. Masterpieces of American Jewelry. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2004.

- Proddow, Penny and Healy, Debra. American Jewelry: Glamour and Tradition: New York NY: Rizzoli, 1987.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

Notes

- John Singleton Copley: Jeremiah Lee (39.174) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.↵

- Charles Willson Peale: George Washington (83.2.122) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.↵

- John Ramage: George Washington (24.109.93) | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.↵

- Proddow & Healy, p.12↵