Mid-Victorian women were competing with men for jobs as clerks, teachers, and factory inspectors and they were fighting to win the right to vote. Suddenly they had their own money, and a change in the laws c.1870 allowed them to keep what they earned. Women’s fashion was undergoing a radical transition and enormous crinolines expanded to ridiculous proportions and restrictive corsets resulted in expanding décolletages. Women’s earlobes re-emerged with a new backswept hairstyle that sent curls cascading down the neck. A passion for ancient history fueled by archaeological discoveries and written accounts of the exploits of ancient civilizations made this period ripe for revivals of ancient jewelry styles. The jewelry business flourished throughout Europe.

In France, the Second Empire, led by Napoléon III and his Empress Eugénie, was influencing fashion with a revival of an elaborate, courtly lifestyle. Eugénie favored eighteenth-century fashion and had the Crown Jewels restyled à la Louis XVI. Eugenie’s passion for emeralds caused a sensation in France making them almost as desirable as diamonds. Tiaras were suddenly a jewelry wardrobe requirement and Eugénie favored elaborate scrollwork with diamond and emerald drops. They are also credited with the revival of the cameo industry as Napoléon led the way with his passion for collecting.

The revival of jewelry styles from the Renaissance and Middle Ages, begun in the 1850’s, continued. Working in the neo-Renaissance style throughout this period was Carlo Giuliano. He embraced the Renaissance aesthetic and adapted its designs to suit the Victorian woman. His popular lozenge-shaped pendant set with pearls, gemstones, and enamel were suspended from multi-strand seed pearl necklaces.

As a result of the work on the Suez Canal in the mid-1860s and the Egyptian excavations of Auguste Mariette and the resultant exhibit of Egyptian treasures at the Exposition Universelle in 1867, a fascination for all things Egyptian developed. Giuliano embraced this wealth of new motifs from the ancient world with his use of scarabs and other Egyptian symbols. French jewelers Mellerio, Boucheron, and Fromet-Meurice also adopted the style by creating winged scarabs, falcons and other Egyptian influenced motifs decorated with green red and blue enamels.

The Renaissance and Egyptian revivals were joined by a classical revival of Greek and Etruscan styles. An avid search was made for the secret of Etruscan granulation with jeweler Fortunato Pio Castellani claiming to have found the answer in a remote area of the Apennines. Using his granulation skills and other ancient jewelry techniques, he went on to produce many amazing replicas of the jewels discovered in the excavations of these ancient Greek civilizations. In 1858 Fortunato Pio’s son Augusto continued to reproduce Greek and Etruscan jewelry along with Renaissance and Scandinavian jewelry. The jewelry enhancement techniques of engraving and chasing were replaced by the revival of ancient techniques to create matte and shiny surfaces, depth and relief were provided by corded wire, filigree, and granulation. Greek and Roman coins were also featured, set prominently in these archaeological jewels. Castellani’s work spread through Europe and the style was adopted most famously by Fontenay in France, John Brogden and Robert Phillips in London and by Carlo Giuliano, originally from Naples, now settled in London.

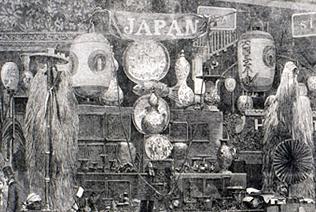

The French expedition to China introduced the West to the use of jade in jewelry. The Mexican campaign resulted in a fad for bejeweled hummingbirds set as brooches and hair ornaments. But it was the opening of trade with Japan that had the most lasting impact on jewelry design. It began with a technique for setting small bits of decorative Japanese metalwork in jewelry. Shibuichi and Shakudo, mixed metal techniques devised by sword makers, found their way to the jeweler’s bench. The distinct lines and motifs of Japanese art would eventually help spawn a new jewelry style – Art Nouveau– that would develop concurrently with the late Victorian period.

A shift from gem-driven design to one that required the gems to adapt to metalwork designs developed. Calibré-cut stones served to outline featured gems. Garnets were often rose-cut to cluster around a carbuncle creating a star or floral motif. A fashion for setting small stones into large ones came about in the 1860s and cabochons featured decorative centers inlaid with a pearl, diamond or even an applied flower or insect. Workmanship was very high in the jewelry industry and craftsmen showcased their skill by creating ever more elaborate cameo habillés.

The 1860s marked the apex of tortoiseshell piqué. This technique was first introduced in England in the seventeenth century by the Huguenots. The naturalistic motifs were completely inlaid by hand and beautiful buttons, earrings, and brooches were produced. When machine-made piqué began production in Birmingham in 1872, the decline in quality led to the demise of the art form. Much of the machine-made piqué was of a cruciform design and the patterns used were rigidly geometric. Machines were, at the same time, enhancing jewelry manufacture and destroying the fine art of handmade jewelry.

Novelty jewelry with its depictions of flowers, windmills, lanterns and other commonplace household items amused the Victorians. Sporting jewelry with motifs depicting horse racing, hunting, fishing, tennis, yachting, and other leisure pursuits was embraced by the novelty-loving public. Napoleon III purchased a horseshoe brooch on a visit to England and they became all the rage upon his return to France.

Reverse crystal intaglios, produced by carving into the back of a rock crystal cabochon, painting the carving and sealing it with a mother-of-pearl backing, was part of this novelty craze. Buttons, stickpins, and cuff links for gentlemen featured whimsical paintings of horses and dogs. For ladies, there were flowers and monograms set in brooches and pendants. Cheaply produced imitations of this art form, cast in glass, soon destroyed the market.

Circa 1860s, stars were the most popular jewelry motif. They were carved into the tops of amethysts and carbuncles, centered on brooches, bracelets, and lockets, and pavèd with pearls, turquoise, opals, and diamonds. These early stars were relatively flat but later in the century, a more dimensional form of the motif would emerge.

Another popular motif resulted in realistically rendered insects: flies, wasps, dragonflies, butterflies, beetles, bees and spiders, set with multi-colored gemstones, landed on the veils, hats, bodice, sleeves, and shoulders of nearly every fashionable Victorian woman. Bees, the emblem of Prince Victor Bonaparte, were particularly fashionable in France.

According to Margaret Flower in Victorian Jewellery:

Mr. William d’Arfey in Curious Relations mentions that in the late sixties ‘Bonnets and veils were covered with every kind of beetle; that at least was the beginning of the mode, but it soon extended itself from rose-beetles with their bronze and green carapaces to stag beetles… Parasols were liberally sprinkled with ticks, with grasshoppers, with woodlice. Veils were sown with earwigs, with cock-chafers, with hornets. Tulle scarves and veilings sometimes had on them artificial bed-bugs… 1

In 1870, in the British Territory of Australia, a major opal discovery was made. Up until that time opals were deemed to bring bad luck. The source of this bad luck story is believed to be the novel Anne of Geierstein written by Sir Walter Scott in 1829. The book featured an opal hair ornament that brought considerably bad luck to its owner. While opals were held to be cursed, the bad luck did not go so far as to plague those whose birthstone is opal. Following a movement led by the Queen, opals were popular again – even with those not born in October, turning up in the most fashionable Victorian jewelry.

The discovery of silver in Virginia City, Nevada in the 1860’s brought down the price and provided a reliable source for the metal. Silver enjoyed a renewed popularity and heavy necklaces and lockets were produced in silver. These large silver jewelry pieces became the most stylish daywear items c. 1880. Brooches and lockets were engraved by hand or machine stamped with monograms, mottos, dates and decorative motifs. The still fashionable Celtic and Scotch jewelry was also produced predominantly in silver.

A revolution in jewelry called secondary jewelry or costume jewelry was in full swing. Gas and steam engines found their way into jewelry workshops and low karat gold and Doublé d’or, (rolled gold) replaced the use of gilt metal in lower-priced jewelry. Sheets of this gold cemented to brass could be rolled paper thin and machine stamped into jewelry items. In order to give these pieces ample weight, they were filled with base metal. Pinchbeck disappeared replaced by this new process. A woman who could not afford pricier jewelry fashions could now have a complete suite of brooch, earrings, and necklace for ten guineas (£10.5).

By the 1880’s brightly colored jewelry had fallen from vogue. The advent of the electric light is believed to have made these jewels look too gaudy. Diamond jewelry was perfect for wear under the new lighting and its popularity soared. In addition, diamonds had been discovered in South Africa in 1867 and they were suddenly plentiful. In another aspect of jewelry manufacture, diamond bruting machines now driven by steam power made it easier to cut diamonds and to achieve a diamond cut with a truly round outline. Settings were becoming less elaborate, almost invisible, and the focus in jewelry design was now on the gemstone.

Another major influence in English jewelry from this period was the mourning of Queen Victoria. Victoria’s mother, The Duchess of Kent, passed away in 1861 followed later in the same year by the death of her beloved husband, Prince Albert. Victoria and the nation were stunned and devastated by grief. In the United States, the first shots of the Civil War were fired marking the beginning of a conflict that would rage on for years. In 1865, the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln deepened this international time of mourning. The observation of traditional mourning periods resulted in a dramatic change in fashion and jewelry.

Victorian mourning jewelry and clothing followed a strict protocol. After full mourning ended, a time that required all black jewelry and clothing, half-mourning ensued with colors such as gray, mauve, or purple being allowed back into the wardrobe. Jet, onyx, gutta-percha, vulcanite, French jet (glass), and bog oak were popular materials for mourning jewelry. Other featured gems included amethysts, cabochon garnets, rock crystal, emeralds, diamonds, opal, pearl, ruby, and tortoiseshell.

Jewelry of the Grand Period

| EARRINGS | Earrings were essential in the Grand Period but their size and style fluctuated widely throughout the era. Archaeological revival gold amphorae and drops decorated with granulation, twisted wire and rosettes dominated earring motifs. Hoops, drops, spheres, crosses, flowers and stars were other favored subjects for earring design. With the Victorian penchant for whimsy, novelty jewelry saw fish, lizards, birdcages, bells, tools and other everyday objects dangle from earlobes c. 1870’s. |

Photo Courtesy of Bonhams. | TIARAS & FERRONIERES | Tiaras were revived in the Grand period and the 1860’s saw tiaras designed with wreaths of gold leaves or gabled points with sloping sides and Louis XVI styles with gemstone drops. The 1870’s heralded the arrival of the Tiara Russe, a diamond spike motif that later developed into a radiating motif. Brooches were also pinned in the hair and elaborate combs pierced the chignon, or stretched to great lengths as bandeau. |

| NECKLACES | Necklaces were worn close to the Shorter necklaces with flexible tubular links suspending a pendant or trio of pendants (or more) were the style. Motifs from ancient Greek and Etruscan civilizations inspired urns, amphorae and masks while the Egyptian and Classical archeology provided inspiration for the use of enamel, mosaics, cameos and intaglios. The Léontine chain, (named for and actress of the period) was made of a woven gold ribbon which suspended a watch hook on one end and a tassel on the other and wrapped around the neck with the two ends joined by a slide in front. |

| BROOCHES & PINS | Brooches were large and usually Round brooches were produced c. 1860’s with a central cabochon or enameled dome in a decorative frame. Brooches often doubled as pendants and to facilitate this double duty the orientation of the brooch went from horizontal to vertical. Greek, Etruscan and Egyptian design influence included the use of corded wire and granulation to accent the borders of Roman mosaic, cameos and portrait miniatures. Celtic and Scottish pebble brooches continued to intrigue the fashionable Victorians. Realistically rendered bugs, hummingbirds and floral sprays set en tremblant were created in a naturalistic style along with stars and feathers. Sporting brooches with saddles, stirrups, caps, clubs, balls and horseshoes were considered essential for daywear. |

| BRACELETS | Bracelets were the most popular item Bracelets of gold with curb links, ship’s cable links or flexible links with a central gem-set motif or decorative buckle were worn in multiples. Bangles designed as wide gold bands with a central plaque or motif, which could often be detached, and pavéd with gems were in serious demand. Mosaics, shakudo plaques, cameos and intaglios were mounted as central elements on straps or bangles and several could be set in a line, each framed with gold, in the archaeological style. |

| PENDANTS | Suspended from pearls, chains, and ribbons, pendants were the favored neck ornament of the era. Lozenge-shapes and cruciforms were enameled in the Renaissance style and gem-set, often including a chain with matching enameled plaques. Memorial and sentimental lockets became a very important fashion accessory on both sides of the Atlantic. Containing locks of hair from a loved one, daguerreotypesand other mementos, they kept the memory of a dear one close to the heart. Large oval-shaped gem-set and enameled lockets with applied monograms, stars, insects, buckles and serpents were created at the same time as classically inspired urns and amphorae in matte gold with granulations and corded wire. Chased silver lockets appeared in the late 1870s. |

| PARURES | Archaeological revival gold parures, sometimes with enamel or small gemstones were popular as were those composed of carved coral, cameos and tiger claws. Diamond and gemstone suites with a brooch and earrings or pendant and earrings were abundant, but full parures of precious stones were rare. Demi-parures with adaptable brooch/pendants and earrings that could double as choker elements were in vogue. |

| RINGS | Snakes made an appearance in the Wide gold bands featured a central star-set or claw-set gem or a navette-shape (boat-set) with a trio of star-set stones gained popularity alongside cluster and half-hoop rings. Gypsy-set rings that could disguise a doublet stone, or protect a valuable one, turned up c. 1875. Coiled snake rings with gem studded heads were still in vogue. Memorial rings were designed as wide bands lined with hair or black enamel. |

Timeline

Mid (Grand) Victorian Period

General History

- Prince Consort Albert dies; Victoria enters a prolonged period of mourning.

- U.S. Civil War begins (1861-1865); Lincoln inaugurated.

Jewelry History

- Wearing of (black) mourning jewelry required at British court until circa 1880.

- Fortunato Pio Castellani turns business over to son Augusto.

General History

- International Exhibition held in London..

Discoveries & Innovations

- Japanese decorative arts exhibited for the first time in the West.

Jewelry History

- Archaeological revival gold jewelry exhibited by Castellani of Rome at International Exhibition.

- Reverse intaglios by Charles Cook shown at International Exhibition

General History

- Edward, Prince of Wales, marries Alexandra of Denmark.

Jewelry History

- The Idol’s Eye diamond‘s first appearance in recorded history; it is sold by Christie’s

General History

- Paris International Exhibition.

Discoveries & Innovations

- First authenticated diamond, the ‘Eureka’, discovered in South Africa.

Jewelry History

- Egyptian Revival jewelry exhibited at Paris Exposition.

- John Brogden wins gold medal for his jewelry.

- Parisian firm Boucheron begins production of plique à jour enamels.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Celluloid, the first successful semi-synthetic thermoplastic, invented in USA by John Wesley Hyatt; commercial production begins in 1873.

Jewelry History

- Gorham Mfg. Co., Providence, RI, adopts the sterling standard of 925 parts per thousand.

General History

- First trans-continental railroad from Omaha to San Francisco.

- Suez Canal opened.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Diamond Rush begins in South Africa with the discovery of the Star of Africa.

Jewelry History

- Henry D. Morse cuts the Dewey Diamond, largest found in America to date (23,75ct, cut to 11,70 ct).

- American Horological Journal first published, merges with The Jewelers’ Circular to become The Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review.

General History

- Fall of the French Empire.

- Start of a recession in Europe that lasts throughout the decade.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Diamonds discovered in Kimberley, South Africa.

- Japanese craftsmen introduce metal-working techniques and designs to the West.

Jewelry History

- Peter Carl Fabergé takes over his father’s business.

- Influx of European craftsmen and designers into the USA.

- Jewelers’ Circular founded, the first issue published February 15.

General History

- International Exhibition held in London.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Ferdinand J Herpers of Newark, NJ, patents six prong setting for diamonds, introduced as the Tiffany setting by Tiffany & Co. in 1886.

- Black Opals discovered in Queensland, Australia.

Jewelry History

- Celluloid commercial production begins; trade name registered, 1873.

General History

- Universal Exhibition held in Vienna.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Henry D. Morse and Charles M. Field obtain British and U.S. (1874, 1876) patents for steam-driven bruting (diamond cutting) machines.

General History

- Deadwood, Dakota.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Gold discovered in Black Hills of Dakota Territory.

- Patents for artificial coral, tortoiseshell, amber, jet (celluloid).

Jewelry History

- Arthur Lazenby Liberty founds Liberty & Co. of London.

- The Celluloid Mfg. Co. begins jewelry production in Newark, NJ.

General History

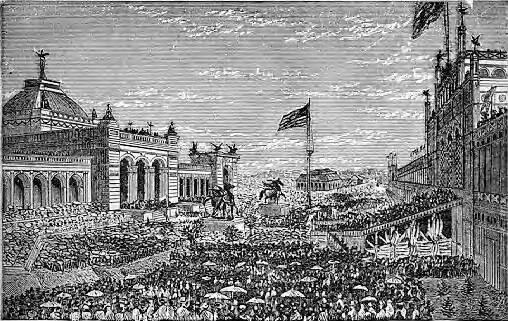

- Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia.

- Wearing of swords banned in Japan.

- Queen Victoria becomes Empress of India.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Alexander Graham Bell patents the telephone.

Jewelry History

- Alessandro Castellani presents and lectures on Etruscan revival jewelry at Centennial Exposition.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Advent of bottled oxygen (liquefied and compressed).

- Successful experiments with chemical manufacture of very small rubies and sapphires in Paris, published by Frémy.

Jewelry History

- Aucoc buys Parisian firm ‘Lobjois’ and changes it’s name to ‘La Maison Aucoc’.

General History

- Paris Exposition Universelle.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Earring covers for diamond earrings patented.

- Tiffany & Co. 128.54 Carat Diamond c.1879.

Jewelry History

- Tiffany & Co. awarded gold medal for encrusted metals technique in the Japanesque style at Paris Exhibition.

- Unger Bros. of Newark, NJ, begins the manufacture of silver jewelry.

Discoveries & Innovations

- T.A. Edison patents incandescent light bulb. .

- Hiddenite, green variety of spodumene, found in North Carolina, USA.

Jewelry History

- Gem expert George Frederick Kunz joins Tiffany & Co.

General History

- Rational Dress Society founded in Great Britain.

Jewelry History

- Child & Child is established in London.

- Cecil Rhodes establishes De Beers Mining Company in South Africa (renamed De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888).

- Mass production of wristwatches begins in Switzerland, introduced in the USA

General History

- First electrically lit theatre, The Savoy, opens in London.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Blue sapphires discovered in Kashmir, N. India.

General History

- Metropolitan Opera House opens in New York City.

More Victorian Jewelry

Sources

- Becker, Vivienne. Antique and Twentieth Century Jewellery: Second Edition: Colchester, Essex, N.A.G. Press Ltd., 1987.

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

Notes

- Flower p.33-34.↵