(1660-1727)

The Georgian period, from 1714 to 1837, was named for, and defined by, the Hanoverian Monarchs of the United Kingdom. These included the four Georges; George I (r. 1714-1727) – 52nd in line to the throne, George II (r. 1727-1760), George III (r. 1760-1820) – the longest reigning king in English history, George IV (r. 1820-1830) along with William IV (r. 1830-1837). This period, which included most of the Eighteenth Century and continued on into the Nineteenth, was one of rapid, worldwide societal change. Extraordinary individuals and events were transforming the entire globe. It was a time of Mozart, Gainsborough and the decorative aesthetics of Rococo, Neoclassicism, and Romanticism. In America it was a period marked by a Revolution, George Washington and explorations by Louis and Clark; in France, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, the French Revolution, Napoleon, Josephine and Marie Louise; in Russia, the reign of Catherine the Great. All of this, combined with great strides in science and world exploration, the advent of rail travel and a changing role for women in society created the perfect backdrop for the creation of the magnificent jewelry we call Georgian.

While the reign of English Kings defines the parameters for Georgian jewelry, stylistically the designs, trends, and ideas were shared internationally and the Georgian aesthetic turned up all over Europe and America. At the same time, on the European continent, styles were developing known as the Louis styles, named after the French Kings Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI. At the dawn of the 19th century, we saw the Empire style of Napoleon Bonaparte. In this century of artistic and political turmoil, there were many forces at work.

Prior to the mid-1700s attempts were made to maintain class boundaries through Parliamentary legislation and Royal decrees stating specifically what items of clothing and jewelry could be worn based on rank or income. These sumptuary laws were often ignored or flaunted and during the Georgian era, they largely disappeared. As a result jewelry, no longer just the purview of the aristocracy, was now more widely available to the middle class. A lighthearted approach to life and an extreme dedication to social activities created a competitive demand for jewels. In spite of the fact that a great deal of restyling occurred in successive years, so much jewelry was produced, for this wider customer base, that many excellent examples remain available today.

Fashion cultists abounded. Macaronis’, men wearing extreme costumes consisting of bright colored, tight-fitting clothing, red high heels, diamond buttons and buckles and carrying a “quizzing glass,” could be observed circa 1770. Circa 1797, the so-called Incroyable’s created another outlandish gentleman’s fashion that included jackets with large lapels, extreme bicorne hats atop flamboyant hairdos, layers of scarves and walking sticks. Jewelry for women changed fashion from month to month, shapes went in and out of style; dying out in England and remaining popular in France only to pop back up in England. Diamonds and pastes were sparkling everywhere.

The goldsmiths of the day were highly trained technicians, skilled in all areas of gold work, and although Louis XIV died in 1715, at the beginning of the Georgian period, he left his mark on Georgian jewelry. By revoking the Edict of Nantes in 1685 he initiated a massive emigration of Huguenots, most of whom found refuge in Germany, Holland, and England. A large percentage of the Huguenots were artisans and designers. Unwittingly, Louis XIV gave the Protestant world some of the best craftsmen to be found anywhere in the Western hemisphere.

Georgian era gold alloys were 18 karat and higher. Each sumptuous jewelry creation was completely handcrafted. Prior to 1750, and the invention of the rolling mill, apprentices had the task of hand-hammering blocks of gold down to the desired thickness which the master goldsmith could then transform into jewelry. The invention of the rolling mill to roll out uniform sheets of silver and gold streamlined this process and saved a great deal of labor.

Jewelry styles came to be designated as to the time of day they should be worn. During the daylight hours, women wore a necklace or chain with a watch, a cameo or lace pin, small colored stone rings, matching bracelets (worn in pairs as they had been for centuries) and earrings of any length. The chatelaine was the single most important item of daytime jewelry for women and suspended from it were all the items necessary for daily life. Gentlemen could not be seen anywhere without a fabulous pair of status-establishing shoe buckles and buttons made from every conceivable material and studded with diamonds, paste, and gemstones.

Garnet, topaz, emerald, and ruby were popular, and materials from nature were abundant in daytime jewelry. Coral, amber, ivory, pearls along with turquoise, translucent agates and carnelian were used in a variety of ways. Strands of beads, rivière necklaces, parures, cameos, and intaglios all featured these natural gems. Right alongside, and almost equally as popular, were the imitations; paste, faux pearls, opaline glass, Vauxhall glass, tassies and Wedgwood’s Jasperware beads and cameos.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Iron and cut steel jewelry with incredible detail were at their apex during the Georgian era. In an attempt to create gold from base metal, Christopher Pinchbeck created a wonderful alloy of copper and zinc and, in a rather magical way, it became desirable in its own right. These metals along with gold and silver were all utilized as materials for Georgian jewelry.

Timeless longchains were created through the use of various techniques, in a myriad of shapes, with patterned links, woven or knitted, and were a signature of the period. In France, the collière d’esclavage featured swagged chain of various link designs hooked to central plaques creating a draped symmetry.

The evening was an entirely different story, rose cut and mine cut, diamonds were abundant at night. What better way to showcase them than the diamond rivière (river of light). Delicately linked together was a glimmering line of silver collets set with graduated, matched diamonds that formed a shimmering circle around the neck. So popular was the rivière that they were also made with pastes and colored gemstones set in gold, silver, and pinchbeck, sometimes foiled and often suspending a matching detachable pendant. The rivière was an instant classic, often escaping the temptation for redesign. In 1767 jeweler James Cox invented a process to back the silver with gold to prevent these magnificent necklaces from marring the skin or clothing with tarnish.

Parures glimmering from their satin-lined fitted leather boxes often included as many as sixteen items. Each item was created to compliment the other and ultimately highlight the lady’s gown. Set with matching gemstones, diamonds or pearls and a cohesive theme, the parure was an essential part of every woman’s jewelry wardrobe.

The technical ability to mount gems with an open back had evolved from the earlier closed-back mounting style, but it was not often seen in Georgian jewelry. The use of tinted and silvered copper sheets to “foil” back many gems of the Georgian era required the continued use of a closed back. A foil and closed-back combination is a signature element in Georgian jewelry. This process served to brighten diamonds and intensify colored stones, creating a richer, gleaming effect enabling the diamonds to twinkle and scintillate in the candlelight. While the foiling may have tarnished and faded with time, it is still appreciated as a quintessentially Georgian technology.

Necklaces evolved from ribbon-style chokers early in the period to grand glittering cascades of gems. Harlequin festoons of colored stones and monochromatic suites of diamonds and paste were created to adorn the ever-increasing décolletage. Cut steel became popular with graduated drops, flowers, and garlands. Starting in England with “up-cycled” horseshoe nails, the trend caught on in France c. 1759 when King Louis XV “requested” that jewelry be donated to the state in order to fund French participation in the Seven Years War. The wealthy French adopted cut steel jewelry as a replacement for their donated (or hidden) gems.

Girandole earrings, designed with a central bow-shaped motif suspending two pear-shaped drops flanking a third larger drop, were by far the most loved style for evening wear. Later, pendeloque earrings, comprised of a round or navette-shaped top suspending a bow and a matching larger drop became the preferred style. This evolution of earring style looked as if the outer flanking pendants from girandole style earrings had been removed. Earrings were designed with a hinged wire hook that threaded the ear from back to front and clicked into place on the earring. Another innovation, in 1773, allowed earrings to be “snapped” onto unpierced ears, resulting in more than a little discomfort for the wearer.

Brooches evolved from the demure gemstone bouquets or giardinetti to magnificent naturalistic bouquets set en tremblant. Bows, feathers, crowns, cornucopias, and crosses were other frequent themes from the period. These motifs were often used in the creation of brooches with detachable pendants. Some of these brooches were fitted with loops on the reverse to allow a ribbon or chain to be threaded thereby transforming the brooch into a pendant.

Rings were often styled with a larger central stone surrounded by small diamonds and were produced in every shape imaginable. Often, the large center stone was a foiled “lesser” stone or made of paste. Bands set all around or halfway with gemstones were worn singly or in stacks. Clusters of small diamonds were set in such a way as to appear more dramatic and important.

Magnificent hairstyles required equally magnificent jeweled adornments. Tiaras, coronets, bandeaus and diadems in every motif from naturalistic to geometric were expressed in diamonds and colored gems. Aigrettes, combs, and hairpins decorated with all manner of gems, cut steel and anything that would catch the light, poked out of towering wigs.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Portrait miniatures, hair jewelry, silhouettes and eye miniatures comprised tokens of love and remembrance during the Georgian era. Jewelry designed to feature a plaited lock of a child’s hair was a treasured keepsake for a mother. Women used their own hair to have mementos created for their children, for husbands and for lovers, both secret and acknowledged. The French created “amatory jewels,” brooches or pendants, navette-shaped, with an enamel or pearl frame that centered miniature floral designs rendered in seed pearls often atop a bed of the loved one’s hair. Jewelry made of hair came to a peak near the end of the Georgian era when complete suites of jewelry including bracelets and necklaces were woven entirely out of hair following the many published designs on this craft.

To memorialize the dead there were mourning rings, and other forms of jewelry, set with a “Stuart” crystal (carved rock crystal) cap atop a gold wire cipher or monogram with a hair memento background. Later, these evolved into rings with skulls or skeletons under the crystal and skeleton or bone motif bands with black enamel. Memorial bands were made up, by those who could afford it, to distribute to friends and family and often the deceased made the arrangements for this custom prior to his demise.

Jewelry did not go from “Georgian” to “Victorian” simply as a result of the coronation of a new monarch. Georgian elements and themes continued to be used well into the reign of Queen Victoria and some were revived later in the period. Mourning jewelry, cameos, portrait miniatures, and many other items remained a constant, with stylistic changes, through both periods. The analogy of evolution can be used to describe the fluidity of change from one period to the next, rather than simply abrupt change.

The fate much of the jewelry created by eighteenth-century jewelers fell to the remodeller’s torch. Bringing one’s gems up-to-date with the latest styles was a popular pastime for the affluent and any excuse was employed to take one’s jewelry to be redesigned. Gems seemed to achieve new brilliance when re-set in au courant mountings.

Timeline

Georgian Period

Jewelry History

- The Dresden Green (World’s Largest Green Diamond) First Reported in “The London Post Boy”.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Diamonds and Amethysts (1727) Discovered in Brazil (c.)

Discoveries & Innovations

- Robert Adam is Born (Dies 1792).

Jewelry History

- Georges Frédéric Strass Becomes Famous for Paste Jewelry (c.)

General History

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is Born in Germany (Dies in 1832).

- Roman Vincent Jeuffroy is Born in France (Dies in 1826)

Jewelry History

- Giacomo Raffaelli is Born in Italy (Dies 1836).

General History

- George III Becomes King of Britain.

Jewelry History

- American Goldsmith Paul Revere Begins Making Jewelry (c.)

- Lava Cameos Carved in Italy for Tourists Visiting Pompeii Ruins.

Jewelry History

- Josiah Wedgwood Introduces Fine Ceramic Known as Jasperware in Plaques with Relief Decoration Resembling Cameos, Mounted in Cut Steel, Manufactured by Matthew Boulton Beginning in 1773.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Die Stamping Machine Patented by John Pickering, Adapted for Inexpensive Jewelry in 1777.

General History

- Louis XVI Becomes King of France.

General History

- American Revolution Begins, Congress Adopts the Declaration of Independence, 1776.

Jewelry History

- “Caesar’s Ruby” (Carved Rubellite Tourmaline) Presented to Catherine the Great of Russia.

- Azim-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Arcot Presents Queen Charlotte of Britain a Gift: Five Diamonds of which Two are the Arcots.

Jewelry History

- Burmese Jadeite Imported into China.

Discoveries & Innovations

- French scientist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier succeeds in melting platinum from its ore using pure oxygen.

Jewelry History

- Benedetto Pistrucci is Born (Dies 1854).

Jewelry History

- Eye Miniatures Popularized by Prince George of England.

- Nizam Ali Kahn of the Deccan Presents the Hastings Diamond as a Gift to King George III.

Jewelry History

- Marc Étienne Janety, Goldsmith to Louis XVI of France, Crafts a Sugar Bowl Out of Platinum. <

General History

- George Washington, elected first President of the USA. He dies in 1799.

- French Revolution Begins, Ends 1799.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Chrysoberyl identified as mineral species by German Geologist A.G. Werner.

- Brazilian Chrysoberyls in Portuguese Jewelry, Last Half of 18th Century.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Titanium Discovered by British Clergyman Wm. Gregor, Isolated 1910.

Jewelry History

- Seril Dodge of Providence, RI, Advertises Offering of Jewelry Items Made to Order, Sells Business to Half-Brother Nehemiah, 1796.

General History

- Napoleonic Wars Begin. They End in 1815.

General History

- Thomas Jefferson Elected President of the USA.

- Jem Belcher Wins his National Boxing Title.

Discoveries & Innovations

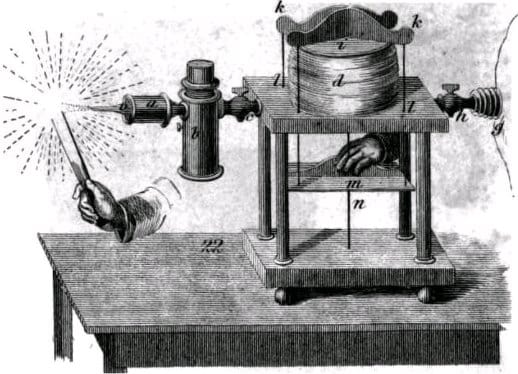

- Alessandro Volta Invents the First Battery, the Volta Pile.

- Wollaston & Smithson Tennant Begin Collaboration, Create Commercial-Grade Platinum, they Discover Platinum Family of Metals: Palladium and Rhodium in 1802; Iridium and Osmium, 1803.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Robert Hare of Philadelphia Invents Oxyhydrogen (‘Gas’) Blowpipe.

- Recognition of Tourmaline “Family”.

- Niobium Discovered by British Chemist Charles Hatchett.

Jewelry History

- E. Hinsdale Establishes First American Factory for the Manufacture of Fine Jewelry in Newark, NJ.

General History

- Napoleon Crowns Himself Emperor of France.

Discoveries & Innovations

- The Regent Diamond is Set in Napoleon’s Ceremonial Sword which he Carried to his Coronation.

- Royal Ironworks of Berlin opens, jewelry production starts in 1806.

General History

- George III Declared Insane; Regency Period Begins in Britain.

General History

- 1812-1815 War Between Great Britain and the USA.

General History

- 1813-1815 Prussian War of Liberation Against Napoleon.

Jewelry History

- Berlin Iron Jewelry Made in Germany as Patriotic Gesture During War of Liberation: “ich gab gold für Eisen” (I Gave Gold for Iron).

General History

- Kingdom of France (Bourbon Dynasty) Restored, Louis XVII Becomes King.

Jewelry History

- Fortunato Pio Castellani Established Workshop in Rome, Begins Study of Granulation in Ancient Goldwork in 1827.

Discoveries & Innovations

- The Gas Blowpipe by E.D. Clarke is Published.

General History

- George III of Great Britain dies, George IV becomes King.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Platinum Discovered in Russian Ural Mountains.

- Ancient Gold Work Discovered in Etruscan Excavations.

- Tourmalines Discovered in Maine, Mines Opened from 1822 (c.)

General History

- Charles X Becomes King of France.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Pin Making Machine for Straight Pins Patented in England by L.W. Wright, by J. Howe in the USA in 1832.

General History

- Andrew Jackson Elected President of the USA.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Sir Walter Scott’s Anne of Geierstein is Published, Describing Opal as ‘Misfortune Stone’.

- French Hallmark for Doublé d’Or (Rolled Gold) Introduced by Paris Mint.

General History

- Louis-Philippe I becomes king of France.

- George IV of Great Britain dies, and William IV becomes King.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Indian Rubber Elastic First Appears in Women’s Clothing.

- Godey’s Ladies Book First Published.

- Claw/Coronet Setting of the Middle Ages Revived.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Emerald Discovered in the Ural Mountains, an Important Source of Emeralds in Europe in the 19th Century.

Jewelry History

- Bailey and Kitchen Opens Shop (Bailey, Banks & Biddle) in 1832.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Alexandrite Discovered in the Ural Mountains in an Emerald Mine, Named After Czar Alexander II.

Discoveries & Innovations

- Edmund Davey Discovers and Identifies Acetylene

- USA Patent Act Passed. U.S. Patent Office Issues Patent Number 1.

Related Viewing

Shop at Lang

Georgian Garnet Garter Pin

Initiate yourself symbolically into the British Order of the Garter* with this delightful Georgian/early-Victorian (circa mid-19th century) adornment, exquisite…

SHOP AT LANG

Georgian Interlocking Witch's Heart Garnet Brooch

A popular motif during the Victorian era, the witch's heart--the tail of which twists to the right--symbolized love, loyalty, betrothal, and even protection (th…

SHOP AT LANG

Georgian Cabochon Garnet Pendant/Brooch

Dating back to the 1800s this romantic work of wearable Georgian art, measuring 2 3/4 inches long, highlights a pair of cabochon garnets imbued with a deep wine…

SHOP AT LANG

Sources

- Bennett, David & Mascetti, Daniela. Understanding Jewellery: Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008.

- Dawes, Ginny Redington Dawes with Collings, Olivia. Georgian Jewellery: 1714-1830: Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2007.

- Evans, Joan. A History of Jewellery: 1100-1870: Boston, MA, USA: Boston Book and Art, Publisher, 1970.

- Romero, Christie. Warmans Jewelry: Radnor PA: Wallace-Homestead Book Company, 1995.

- Scarisbrick, Diana. Jewellery in Britain: 1066-1837: Whitby Hall, Whitby, Norwich: Michael Russell Publishing Ltd., 1994.