The human relationship with animals is as old as time. A motif for decorative art since Prehistory, fauna reflected our complicated affiliation with the creatures that both threatened and sustained our survival.

In early cultures, animals worn on the person or interred with the deceased conveyed specific meanings that were obvious to everyone at the time. Some were ascribed evil deterrent, or apotropaic, qualities, while others symbolized specific animal behavior or represented the character of omnipotent gods and goddesses. In a world that often seemed puzzling or overwhelming, recognizable images of animals helped the ancients to make sense out of confusion and to deal with events and circumstances that appeared to be out of their control. Each culture favored animals indigenous to its area whose behavioral characteristics people associated with superstition or magical powers.1

Whether adorning Egyptian pyramids, or prehistoric cave dwellings, or representing a regiment or other affiliation, when formed by early jewelers, each faunal design carried a symbolic presence. Like the metaphysical attributions of gemstones, these analogies sprang from religion or spiritual affiliation, superstition, good and evil, community or affiliation, and just about any other theme you can imagine. Every civilization, past and present, embraced symbolism and mysticism, expressing it physically in the decorative arts.

Beginning circa the 19th century, animals often both symbolized something the wearer wished to convey and were purely decorative simultaneously. The archaeological explorations and resultant stylistic revivals often inspired by the Campana collection and ruins such as Pompeii, featured not only ancient jewelry techniques lost to time but exquisite animal depictions. The exploration of Egyptian tombs and the opening of the Suez Canal brought us inspiration from the ancients who worshiped animals as gods and goddesses. All this, combined with the emerging middle class and resultant leisure time spent pursuing sports and new fashions, impelled animal depictions to the apex in jewelry design. Even in the enlightened 21st century, many people still adopt a personal “spirit animal” to represent them. The following explores fauna rendered in jewelry for this modern age.

Animals

Dogs are our most beloved companions, protectors, and workers. Once seen as nasty creatures, eventually humanity domesticated dogs, training them to aid in the hunt, herd sheep, provide emotional support, and assist those with disabilities. Circa the 18th century, decorative arts began to feature dogs as pets. Faithfulness became the dog’s symbolic attachment, depicted at their master’s feet and often with a masculine theme such as hunting.

As the aloof masters of their domain, cats explore our world with their own agenda, occasionally deigning to acknowledge our existence, usually at dinner time. Considered gods by the Egyptians (an attitude they continue to proclaim), it was rat hunting during the 14th-century Black Death that earned cats their keep and a place in our homes. Sometimes they’re paired with their nemesis, the mouse (much cuter and less fearsome than rats), but most often make a solo appearance.

Horses, long domesticated for military use, transportation, hunting, and farming, it is often their accouterments that we display in jewelry form. Signaling luck and fortune, the horseshoe and distinctively flared horseshoe nails are popular motifs. Race horses (and sometimes just their hoofs), complete with appropriate tack, make an appearance atop stickpins, on cuff links, and brooches.

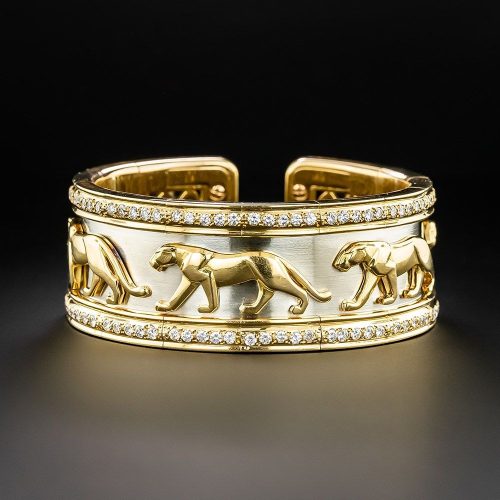

Strength and power are depicted in the “King of Beasts,” the lion. Displaying his prowess, he is often depicted “rampant” on hind legs, roaring at the observer. The lion is still in use today in logos and other representational artworks, continuing to claim the top spot as a symbol for power. Conversely, tigers lost their claws to the jewelry industry as an avant-garde fashion material while valued in their native India as protection from evil. Panthers, employed so brilliantly by Cartier, evoke a combination of power and sensuality.

Birds

These heavenly creatures move among the gods, flying high above mere earthbound mortals. Once viewed as messengers from the heavens, they continue to be employed as spiritual symbols by many religions today. Christians view the dove as an embodiment of the Holy Spirit, and folks of many cultures view it as a symbol for peace. Romance and love have long been represented by doves and pigeons, along with swans, which mate for life, representing married love.

Eagles have been used by governments in their emblems and medals to symbolize power and strength.

Once the Western world was exposed to the incredible Asian art and design aesthetic, jewelers and other artisans moved swiftly to embrace it. A popular subject adapted by Art Nouveau jewelers was the crane. Peace, luck, and long life are attributed to the crane in Japan, where folding one thousand origami cranes within one year is believed to make a wish come true. Other countries also revere the crane, China for immortality, Germany as a messenger of God, Greece for purity, and, conversely, India for betrayal.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. 2

Bats, airborne mammals, are not technically birds. They have been included here because of their dramatic symbolism. Bats are a Chinese favorite, expressing good fortune and happiness. Alternatively, the Western biblical interpretation sees them as symbolic of the devil. While they are feared by many, you have to admire their amazing abilities. Bats have an echo-location built-in that allows them to maneuver in large groups safely (even in the dark). In the positive column, they are wonderful at keeping the insect populations low.

Hummingbirds have symbolized love and peace to Native American tribes and were viewed as warriors by South Americans. Their unique attributes lend themselves to many interpretations. They are small but mighty; they have the ability to shut down completely when necessary, enjoying a near-rebirth upon awakening. Their iridescent feathers make them incredibly beautiful, and in an odd stylistic turn during the Victorian Era, hummingbird heads were mounted as jewelry. According to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London:

Jewellery using hummingbird feathers was first made in England by Harry Emanuel. He was a jeweller in London, and took out a patent for his method of using the feathers in jewellery in 1865.3

Insects

Once again, the opening of the cultures of the East to the Western world in the 19th century brought a revolution in the jewelry world in the form of insect-inspired jewelry. Butterflies symbolize grace and beauty to most, but during the First French Empire, love was the preferred interpretation. Wings extracted from butterflies can be found as a decorative element in butterfly brooches and other designs. Art Nouveau embraced the butterfly, superimposing it on sinuous beauties, and adapting it in Japoniste style on every jewelry form possible.

Once again, the opening of the cultures of the East to the Western world in the 19th century brought a revolution in the jewelry world in the form of insect-inspired jewelry. Butterflies symbolize grace and beauty to most, but during the First French Empire, love was the preferred interpretation. Wings extracted from butterflies can be found as a decorative element in butterfly brooches and other designs. Art Nouveau embraced the butterfly, superimposing it on sinuous beauties, and adapting it in Japoniste style on every jewelry form possible.

Butterflies were another popular motif. The butterfly was traditionally associated with transience and the rebirth of the soul, and it could also be a symbol of romance. It fitted well with the collection of jewelled bats, spiders, and insects that bedecked contemporary women’s dresses.4

Spiders, often a creature inspiring fear and fright, were nineteenth-century good luck symbols. Along with their intricately woven webs, spiders had been viewed by earlier tribal warriors as providing invincibility and invisibility. The web could be pierced but not destroyed, and the web’s visibility challenges propelled an interpretation that it could be a cloaking device.

Once accepted as models, insects became objects of serious study for jewelry designers who readily adapted them into small, yet richly varied formats. A 1904 article in The Craftsman explains their appeal: ” The singular appearance of insects results not only from the tools and accessories with which they bristle, but also from the immobility of their countenances, from the absence of all expression in their faces. They are knights who have arrayed themselves in their most splendid vestments. Nothing is too beautiful for them: velvet and silk, precious stones and rare metals, superb enamels, laces, brocades, are lavishly used in their garments. Emeralds, rubies and pearls, golds dull and burnished, polished silver, mother-of-pearl mingle, chord, or contrast with one another. They create the sweetest harmonies and the most daring dissonances.”5

Bees, ever associated with industry and hard work, became an Art Nouveau favorite along with wasps, beetles, and flies. Cicadas and grasshoppers were also well represented.

Dragonflies were another beloved symbol pulled from the Japanese aesthetic. Samurai warriors revered them for their ability to face their enemies head-on. They are extremely agile and have flying abilities second to none. Dragonflies were exceptionally well represented during the Art Nouveau period. Plique-à-jour enamel was artfully applied to create incredible wings for these ethereal creatures.

The scarab beetle was a sacred symbol in ancient Egypt, guiding passage to the afterlife. These revered vermin became a popular motif with the Egyptomania that swept the Western world from the end of the 18th through the first quarter of the 20th centuries.

If these bejeweled bugs give you a shiver, just imagine that for a brief period in the late 19th century, live bugs were proudly pinned to lapels. Additionally, dung beetle carapaces were set in precious metals and displayed as jewels.

Aquatic Creatures

Denizens of the sea did not enjoy the same 19th-century popularity as other creatures, with few exceptions. The explorers circa the 16th century had stripped away the ancient fears of the oceans and all that dwelt within. Christianity adapted the Greek word for fish, ichtus, as it represented the initials of the phrase “Iesous Christos Théou Uios Sôter (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour)”6 Thus, the fish came to symbolize Christianity. In Asia, carp were used to portray courage, strength, and endurance. Art Nouveau seized on the carp motif and employed it beautifully in their designs.

Seashells were well represented as personal adornment throughout jewelry history. They were one of the first items from the natural world adopted by our ancestors to be adapted and worn as jewelry. The modest seashell has been associated with femininity, fertility, and love since ancient mythology presented us with Venus rising from the sea on a shell. Over the millennia, a myriad of religions and shell aficionados have ascribed more meanings than can be listed here. Precious metal and gemstone versions of all manner of shells are a motif with popular appeal.

These multi-talented mollusks also became an in-demand jewelry material, well-suited to being carved into amazing cameos. Also, let’s not forget that from within they produce pearls, another beloved gem for personal adornment. In the mid-20th century, natural shells were set into jewelry in a very popular style. Wrapped in gold wire with precious gemstone accouterments, the humble shell was elevated to haute couture.

Twentieth-century fashionistas came to revere our underwater dwellers as whimsical, wearable fun. Their sinuous flowing forms lend themselves to billowing shapes and interesting dimensionality. Nearly anything indigenous to the sea, octopus, seaweed, dolphins, etc., has been rendered in precious materials and worn with pride by their owners.

Reptiles & Amphibians

The snake is probably the most represented reptile in the jewelry arts. They Symbolized rebirth through their skin shedding and reflected negative connotations like cunning and temptation, from Biblical references. Ancient popularity of these reptiles, held in contempt by more modern standards, achieved a resurgence in esteem with archeological exploration. The sinuous nature of snakes makes them an easy design to render in rings, bracelets, necklaces, etc. They enjoyed maximal jeweled popularity in the 19th century, regardless of the symbolism perceived by the wearer. The ouroboros, an ancient symbol of the cyclical nature of time, morphed into a symbol of eternal love.

It [snake] achieved prominence as a design source when Queen Victoria wore a coiled snake bracelet for the opening of her first Parliament in 1837. Then, for their betrothal, Prince Albert presented her with an emerald-set serpent ring on which the snake biting its tail, representing eternal love, evoked a symbolism dating to the ancient Greeks. That image, when worn on the wrist of a Victorian lady, was seen as a token of love.7

Salamanders were popular critters to render in precious metal and gems, especially the newly discovered demantoid garnet, which suited the salamander to a tee! In ancient times, these cold-blooded beasties sparked the assumption that they could put out fires simply by their cool nature. This invoked the name “fire lizard” from the Greek. Eventually, they came to symbolize Christian virtue, although still rendered with fire.

Frogs, turtles, and alligators are all well represented in wearable form. Frogs are symbolic of metamorphosis as they move through their stages of life. This might explain the fairytale belief that kissing a frog could transform it into a prince, perhaps a final step from tadpole to titled human? This princely fantasy, perchance, plays into their bejeweled popularity. On the other hand, our ancestors believed that frogs represented ancient wisdom. An interesting dichotomy, to be sure.

Mythology

Tall tales of dragons, mermaids, sphinxes, and other make-believe creatures span the millennia. It’s no wonder artisans have used their imaginations to bring them to metaphorical life. The late 19th century was replete with monsters, griffins, and bejeweled beauties entrapped as butterflies and flowers.

Dragons have long represented the devil as slain by saints and angels; alternatively, they are viewed as power and good fortune in Eastern cultures. The dragons artfully rendered in jewelry represented both Eastern and Western aesthetics, making for a wide variety of enticing designs.

Griffins, with a lion’s body and an eagle’s head and wings, grew from the imagination of the Assyrians. Earth and the heavens unite with these symbols of the power of both regions. Renaissance Revival jewelry revitalized griffins in the 19th century with wide appeal.

Mermaids, singing their siren songs and posing coquettishly atop rocky sea outcroppings, have been the stuff of legends for centuries. Tales of sailors lured to their death and other disasters imbue these mythical creatures with a shiver-inducing sort of attraction. A bevy of these beauties was rendered alongside their menagerie of mythological beasts. Worn together, they would make a Beauty and the Beast(s) aesthetic. Hmmm, tempting…

Famous Jewelers

In the 20th century, a dramatic shift occurred from philosophical symbolism to iconic emblems of the maisons that designed them. Each iconic jewelry collection is careful to establish its unique and, therefore, eminently recognizable identity. These memorable critters are highly collectible, and many continue to be produced.

Cartier’s Panthère was one of the first and most tenacious of the beasts to symbolize a major jewelry house. These magnificent panthers are rendered both realistically, albeit with gemstone coats, and abstractly, with panther elements used to represent the iconic style.

According to Van Cleef & Arpels, butterflies embody femininity and elegance. Their extensive collection of jewels based on the motif remains a classic with savvy consumers worldwide. Since the 1950s, their “Lucky Animals” collection has been a whimsical favorite.

Bulgari has employed the sinuous qualities of the humble serpent since 1948. As reported on the Bulgari website, their Serpenti line is their eternal icon symbolizing transformation and rebirth.

The website of David Webb proudly proclaims, “Women are tired of jewelry-looking jewelry and they want one-of-a-kind pieces… Animals are here to stay.” Webb’s iconic enameled and bejeweled animal collection, “Kingdom,” features a myriad of creatures from asps to zebras, both realistic and whimsical.

Hermès, an equestrian outfitter for the haute couture rider, has an extensive line of jewelry evoking horse tack. These stylish bits of wearable horsey hardware are just as popular today as they were at their inception, c.1950s.

Trianon Gent’s and Lady’s jewelry features all types of shells and the pearls found within. According to their website, all natural elements are ethically sourced. Their collection is easily identifiable as the shells are accented by gems, pearls, and precious metals. A stingray line employs shagreen in unique and clever ways.

Kieselstein Cord has spent the last four decades bedecking their clients with unique interpretations of the faunal world. The “Goddess Collection” features feminine creatures with arachnid appendages. “Midnight Summer Dreams” is replete with frogs and butterflies. And let’s not forget his iconic “Alligator” and “Crocodile” Collections.

The subject of faunal jewelry is an extensive one and I could go on and on discussing these delightful creatures. Suffice it to say, bugs and critters are here to stay!

Related Reading

Sources

- Church, Rachel. Brooches and Badges. London: Thames & Hudson, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2019.

- Mauriès, Patrick, Possémé, Evelyne. Fauna: The Art of Jewelry. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

- Tennenbaum, Suzanne, Zapata, Janet. Jeweled Menagerie: The World of Animals in Gems. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

- https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1993-0205-1 © The Trustees of the British Museum, Accessed 06/18/25.

- https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1126618/earring/ © Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Accessed 06/18/25.

- Also Accessed Websites for: Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Bulgari, David Webb, Hermès, Trianon, and Kieselstein Cord, June, 2025.

Notes

- Tennenbaum, p.6↵

- Necklace, gold, with seven pendants each in the form of emerald green and ruby-topaz hummingbirds’ heads, the feathers attached to a gold backing; the pendants are strung on foxtail chains; contained in the original shaped leather box, with maker’s name printed inside the lid on the silk lining. Each pendant bears an applied trade label on reverse and patent number. © The Trustees of the British Museum.↵

- ©Victoria & Albert Museum, Accession #AP.259-1875.↵

- Church, p. 57↵

- Tennenbaum, p.13↵

- Mauriès, p.65,↵

- Tennenbaum, p.15↵